American Ideologies Past, Present, and Future

From Puritanism through Liberalisms to the Tech Right

The following is a bullet-point essay developed from my speaking points for a recent interview with Radio Courtoisie. As most of my readers are non-francophones who cannot understand the show, this will be of interest to anyone interested in what I spoke about.

Since since independence in 1776, the United States has been profoundly influenced by three broad founding ideologies or value systems:

Protestantism, notably the Puritanism of the first settlers, which emphasizes right behavior and conscience. The latter, implying struggling to embrace and live up to sincere moral belief, has been a great factor of instability and change in American culture, leading to frequent religious split-offs and sharp self-criticism for failures to meet moral ideals.

Classical liberalism, as originally expressed by John Locke, emphasizing the ontological precedence of the individual over society and individual freedom as the ultimate social end. In drafting the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson expressed liberalism’s most celebrated encapsulation: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Classical republicanism, reflecting doctrines of popular sovereignty and lessons learned from the Greco-Roman political experiences, emphasizes civic virtue, promotion of and sacrifice for the common good, and the creation of a viable nation-state. This is institutionally embodied in the U.S. Constitution (which post-dates independence by 11 years!) and is most memorably expressed in the Preamble: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

These three ideologies are partly contradictory and certainly often in tension. Much of American history has been the playing out of these different ideological strains, and different interpretations of them, over time.

Liberalism is essentially universalist and revolutionary by virtue of the perpetual gap between liberal ideals (especially equality) and societal realities. Founding liberals such as Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson sought to spread liberal ideals abroad, notably during the French Revolution (with decidedly mixed results, Paine eventually being locked up and almost guillotined by the Jacobins). In the early twentieth century, Woodrow Wilson would pioneer the global spreading of liberal democracy as a fundamental principle of U.S. foreign policy.

Republicanism, characteristic of figures like George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams, is more associated with moderation and realism both at home and abroad, with more tolerance for the world’s perceived imperfections.

Christianity, especially varieties of Protestantism, is a powerful underlying factor historically driving much of American civil society (self-organization in churches), family formation, and moral conviction. Religious conservatives continue to be an important component of the conservative coalition. It is only in the most recent generation of Americans that we have seen a European-style drop in religious belief and practice.

All three founding ideological strands have greatly contributed to America’s remarkable demographic, economic, institutional, and moral power.

Over time, America’s dominant ideology or consensus has been liberal democracy, understood as something like republican means (federal power) to secure liberal ends (individual freedom and/or equality).

As already observed by Alexis de Tocqueville, there is a steadily radicalizing egalitarianism in American history. The moral commitment to equality (though often not the reality) extended to equality among nobles (an abolished class) and commoners, then to all white men, to (ex-)slaves, to women, to black people, to all races, to gays, to transexuals, and so on.

Initially, American egalitarianism coincided with localism. Jefferson’s and Andrew Jackson’s brands of democracy empowered common white men and local government against the federal government and urban administrative and financial elites.

At least since Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, egalitarianism has tended to drive centralization: the achievement of real freedom for all is taken to require more federal power (e.g., to prevent discrimination or redistribute wealth to the poor).

Lincoln’s erudite legal arguments and eloquent rhetoric repurposed the Declaration of Independence’s commitment to equal rights—originally expressed to justify independence from Great Britain—to justify the preservation and supremacy of the Union and the expansion of federal power over the states. Liberalism and democracy were fused as America’s raison d’être, as when Lincoln said in the concise (272-word!) Gettysburg address that the Civil War was fought and hundreds of thousands of men had died so that “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The South’s alternative interpretation of the Founding’s liberalism, with rights limited to white men including possible ownership of black people and states’ rights preceding Union interference, was thoroughly defeated.

The basic cycle of American history since the Civil War has been oscillation between small-state liberalism (limited government, states’ rights, tax cuts to preserve individual freedom; i.e. modern conservatism) and interventionist liberalism (more federal redistribution and regulation to spread individual freedom and equality; i.e. modern liberalism or progressivism).

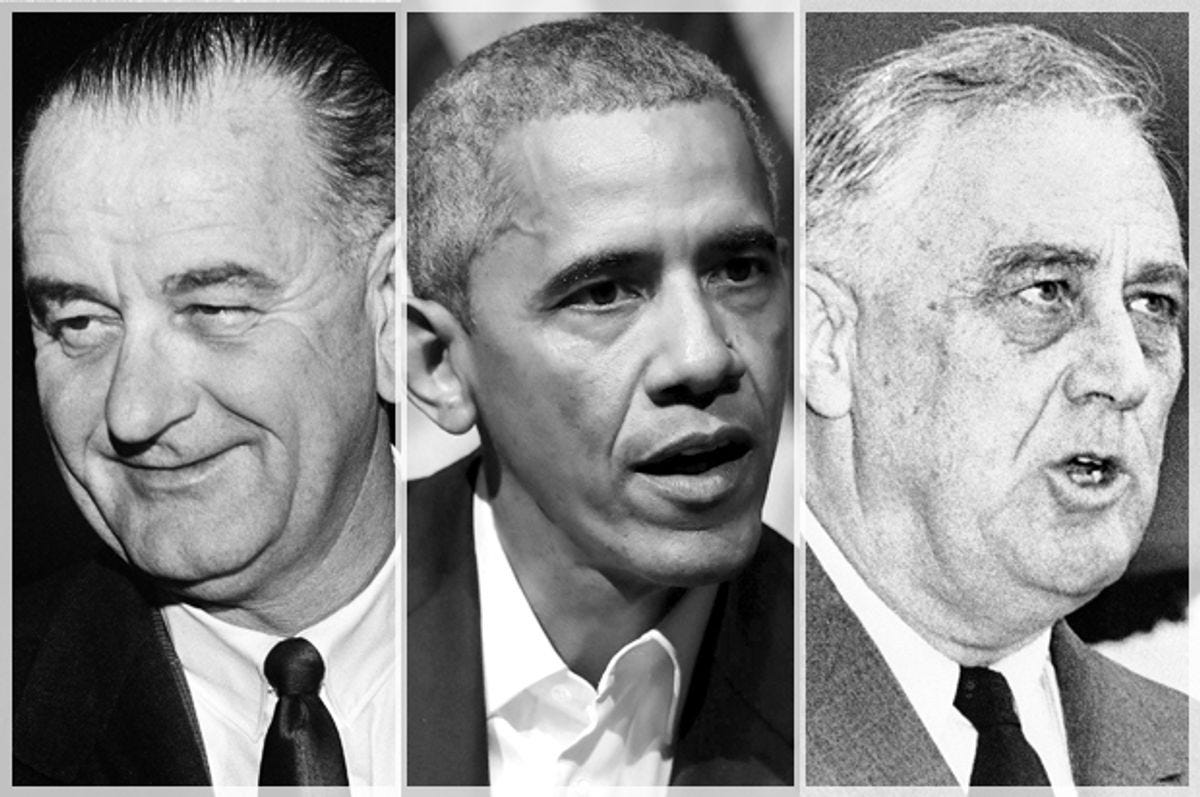

Periods of renewed federal interventionist ambition oscillate with periods of small-state backlash: Lincoln followed by the failure of Reconstruction, Wilson’s global interventionism followed by isolationism, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Lyndon Johnson’s expansion of the welfare state and desegregation, followed by the Ronald Reagan and Newt Gingrich eras of tax cuts and cracking down on crime, and so on.

The long-term tendency is quite clearly one of ever-more egalitarianism (though not actual equality) and centralization, along with a consensus since World War II on America’s Wilsonian mission of universalizing liberal democracy abroad.

The United States’ Wilsonian international promotion of self-determination and liberal democracy has been sincere, inconsistent, and self-interested. (Without going into too much detail, America’s spread of democracy is often checked by immediate U.S. interests or the need to collaborate with some dictatorships to guard against dictatorships perceived to be even worse. The long-term tendency is however quite clear.)

The spread of liberal democracy tends to turn authoritarian rival states into geopolitically innocuous allies (compare Imperial/Nazi Germany with Weimar/Federal Germany, Fascist Italy with Republican Italy, Imperial Japan with postwar Japan…).

The spread of liberal democracy and the doctrine of self-determination both tend to fracture rivals’ empires and even their states along ethno-national lines: dismantling of the European colonial empires, break-up of Yugoslavia, break-up of the Soviet Union, replacement of secular Arab nationalist dictatorships with ethno-religious or tribal civil war in Iraq and Libya. This tends to make both rivals and allies smaller, weaker, and more externally dependent.

Authoritarian states, whatever their other faults, are generally better able to maintain domestic stability, focus on long-term policy goals, and concentrate their societies’ resources for ambitious geopolitical aims (however [un]wise such ambitious attempts may be). In contrast, nations that the U.S. converts to democracy generally lack America’s assets (e.g., the combination of a large population, bountiful natural resources, and high human capital) and so become comparatively weak geopolitically. Remarkably, even the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)—an Atlanticist think-tank—has complained of the degree of European nations’ continued “vassalization” to the United States, reflecting severe technological, military, energy, and, I would add, cultural dependency.

Friendly liberal democracies enjoy significant (but not unlimited) autonomy and become enmeshed in a dense web of economic, cultural, and political ties with the United States. This makes the American “empire” a set of diverse, flexible, and resilient relationships in comparison with the narrow and often brittle relationships among allied authoritarian states, which typically reflect the mood of their executive branches and immediate power-political circumstances, rather than broader sociocultural and institutional ties.

Looking to emerging American ideologies, we have seen significant change in recent years.

On the left, Barack Obama-style social-democratic liberalism (pragmatic, redistributionist, and with an optimistic redemptive narrative about America) has been supplemented by “wokism,” basically more radical forms of racial, feminist, and LGBT activism.

Wokism often entails a delegitimization of American history and society as such, e.g. because of pervasive structural racism or a history of oppression. There is an attempt to purge the public space of offensive symbols, such as by tearing down monuments to Confederate leaders and war dead (even removing a plaque to Robert E. Lee’s horse Traveller) or renaming Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs (Wilson the crusading liberal-democrat abroad was a segregationist at home) and Marie Stopes International (Marie Stopes was a British pioneer of women’s rights and birth control, but also an ardent eugenicist). While much of this is understandable given current moral sensibilities, the trouble with going down this route is you will have to “cancel” virtually all of history for being racist, sexist, patriarchal, etc. No nation’s history can reasonably hold up to woke scrutiny in this sense: everything must be canceled and replaced with a blank slate of moral purity, as previously attempted by France’s Jacobins and China’s Maoists.

More immediately, wokism is quite alienating to the median voter. Moderate Democrats like Obama and strategist James Carville have complained wokism undermines their party’s electability. For example, it seems to me that failure to secure the southern border, more than anything else, is what made the Trump presidency (and potential Trump II presidency) possible. (Quite similar to Brexit in this respect, which in my view would not have occurred had the European Union clearly and vigorously opposed illegal immigration.)

On the right, Trumpian populism has radically changed dynamics since 2015.

To a large extent, Trumpism is more the reflection of Trump’s personality and style than any coherent ideology. This includes “alpha male” aggressiveness, instinctive spontaneity, transactional self-interest (deals), an obsession with personal and national face, and political opportuneness.

On the other hand, Trumpism does express a form of civic nationalism (multiracial nationalism and solidarity based on citizenship), marked by opposition to illegal immigration, protectionist support for American workers, and some poorly articulated isolationist instincts (not really acted upon, but entailing for instance the expectation that allies start paying for their own defense rather than systematically relying on the U.S.).

Trumpism represents a significant addition to the postwar U.S. conservative coalition, traditionally made up of religious conservatives, economic libertarians / business circles, and Zionist neoconservatives. The conservative trinity of key issues was: anti-abortion, anti-taxes, pro-Israel.

Trump’s greatest gift to the traditional conservative coalition has been the appointment of originalist / textualist Supreme Court judges who try to interpret the Constitution according to its perceived original or actual meaning. This is one of the most powerful ways in which classical liberalism and republicanism continue to influence American politics.

Significantly, and against expectations of many on both the left and right, Trump has done more than any other contemporary political figure to reduce the racial polarization of U.S. politics: in some polls Trump has 40% support among Hispanics, a level unheard of for a Republican candidate in living memory. This support is essentially driven by Hispanic men (47% support) and to a lesser extent black men: racial depolarization has coincided with sexual polarization, most women oppose Trump, with support largely limited to married white women.

Being weakly ideological, Trumpian populism is significantly underdetermined. its values do not prescribe what degree of protectionism, immigration restriction, international withdrawal or aggressiveness, welfare (such as support for Social Security), or tax cuts there should be. This makes the political consequences unpredictable and enables Trump to diverge from Republican party orthodoxy on occasion, such as his criticism of the Iraq War or his groundbreaking (for Republicans) support for IVF. Much depends on particular political / bureaucratic dynamics and on Trump’s mercurial decision-making, and it is quite unclear what direction right-wing populism will take when Trump is gone.

Another development has been the rise of the Tech Right (explained in more detail by Richard Hanania), right-wing tech titans and ideologues around Silicon Valley.

Major figures include Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and Marc Andreesen among the businessmen, and Curtis Yarvin (a.k.a. “Mencius Moldbug”) and Nick Land among the writers.

Frankly, I don’t know enough about these figures to say too much about them. If there is a common thread, it may be that all believe that late liberal democracy is no longer meaningfully liberal, but has such centralizing and leveling tendencies as to be increasingly incompatible with human freedom, achievement, and innovation. Most lean towards a libertarian technological accelerationism.

Reflecting in 2009 on the massive expansion of government power with the bank bailouts of the financial crisis, Peter Thiel notoriously wrote: “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” Such concerns from classical liberals do have a distinguished pedigree going back to Tocqueville and the Federalist Papers.

It is unclear to me whether Land and especially Yarvin can be described as libertarian. Yarvin at least has been influential in normalizing technocratic authoritarian capitalist government in the form of a “CEO-monarch,” citing the spectacular successes of China’s Deng Xiaoping and Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew as examples.

Elon Musk thinks of himself as a champion of free speech, has promoted natalism and warned of dysgenic reproductive trends, and has campaigned for Trump on grounds of opposing the “administrative state,” whose regulations he argues will make the kinds of innovation he is pioneering impossible.

The Tech Right is ideologically embryonic but, significantly, as a constituency it looks like it will be here to stay as a powerful factor in national politics.

Significantly, neither Trumpism nor the Tech Right fundamentally oppose immigration. Legal working immigration and especially brain gain have often been praised. See Trump’s “big, beautiful door” for legal immigration, his more recent suggestion of green cards for foreign students graduating in the U.S., or Musk’s suggestion on immigration that “America should be like a pro sports team that wants to win the championship—draft the best players to enable the whole team to win!” Both Trump and Kamala Harris supporters favor border security and high-skilled immigration.

One thing is certain, America’s politics will continued to be marked by polarization and strife. Machiavelli argued that the Roman Republic’s ability to manage conflict between aristocrats and plebs actually strengthened Rome by contributing to the development of goods laws that took the whole community’s interests into account. In America, the capacity to manage acrimonious debate and perpetual change has contributed greatly to American dynamism and renewal, at least once crises were overcome. Let’s hope it stays that way!

"Coming to the end of the century, observing its last twenty-five years, we have seen exactly that limited vision Hofstadter talked about--a capitalistic encouragement of enormous fortunes alongside desperate poverty, a nationalistic acceptance of war and preparations for war. Governmental power swung from Republicans to Democrats and back again, but neither party showed itself capable of going beyond that vision.

After the disastrous war in Vietnam came the scandals of Watergate. There was a deepening economic insecurity for much of the population, along with environmental deterioration, and a growing culture of violence and family disarray. Clearly, such fundamental problems could not be solved without bold changes in the social and economic structure. But no major party candidates proposed such changes. The 'American political tradition' held fast." -Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States (1980, 2003)