Can Techno-Trumpism Work?

3 lessons from a decade of populism

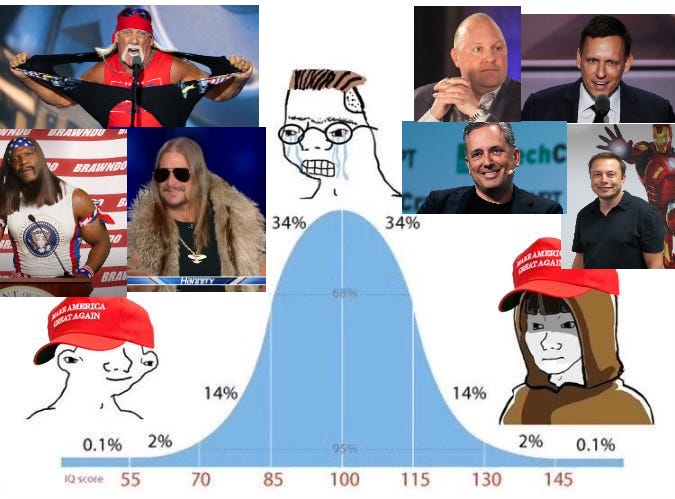

Populism marches on. In the United States, Trumpism has consolidated its hold over the Republican Party. With the choice of of J. D. Vance as Donald Trump’s vice-presidential candidate, MAGA has formalized its alliance with the Tech Right, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and other innovators frustrated by some combination of political correctness, censorship, DEI, taxes, and regulation. Can this real-life midwit meme, an alliance of uneducated proles (“I love the poorly educated,” dixit Trump) and the tech super-elite, actually work?

I have long been of the view that so far as politics is concerned, experience is the best teacher. Human societies, including the exercise of power and the struggles over power, are far too complex to be understood purely by speculative theory. Politics is best known by feeling our way through experience, known through history and current events.

We now have quite some experience with populism with about a decade since populist movements of various sorts have transformed politics across the West. SYRIZA in Greece, the Five-Star Movement in Italy (M5S), Donald Trump in America, Brexit in the UK, national-populist experiments in Hungary and Poland, Javier Milei in Argentina… the list goes on and on. Some of these movements have successfully won and held onto power, while others have receded and become relatively marginal. From observing their various destinies, I draw three lessons for populist movements looking to be successful.

1. Don’t make impossible (economic) promises

Probably the most consistent sign of the non-viability of a populist movement in power is unrealistic economic promises. Everyone wants jobs and money, and many just want to punish the rich in general, so economic promises are very popular electorally, at least in the short term. However, the failure to meet these can be disastrous to a political movement’s credibility.

In 2018, Italy’s new populist party, the comedian Beppe Grillo’s M5S, came to power on an ideologically eclectic program which included promises of replacing the old corrupt Italian political elites, more democracy, and a universal basic income. The only the trouble was Italy being notoriously indebted (135% debt-to-GDP) with a long-stagnant economy (no per capita growth in over a decade). By contrast, M5S’s coalition partners in government, the nationalist Lega Nord, had gotten elected on a promise to crush illegal immigration.

The latter was both extraordinarily popular and much more doable than somehow giving all Italians free money despite a broke economy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini, Lega’s leader, shot to the top of the polls and tried to call new elections—M5S only were able to stay in office by making a deal with the establishment Socialists, whom they had railed against for years. In due course voters punished M5S and the party, while still important, has never really recovered.

Examples of parties being crushed due to inability to meet their economic promises can be repeated ad nauseam. In the wake of the Eurozone crisis, the Socialist French President François Hollande, not a populist, had promised to tame “the world of finance” (“his enemy,” as he called it) make the Eurozone embrace Keynesian deficit spending, and reduce unemployment. None of this was in the capacity of the French President to do. Eurozone policies are decided by many countries and institutions, not least Germany (a then not-broke country) and the European Central Bank (ECB). Hollande, or Flamby as he is known France, withered away to nothing and did not even stand for reelection.

In Greece, the far-left SYRIZA party came out of nowhere to challenge the EU’s austerity agenda. Germany and the ECB said no. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras even submitted this agenda for approval to the Greek people by referendum. Germany and the ECB again said no. Tsipras declined, rightly or wrongly, to leave the Eurozone, which made all his macroeconomic promises irrelevant in the absence of approval from Brussels, Berlin, and Frankfurt. SYRIZA lost power in 2019 and has never recovered. In 2023, the party elected the 36-year-old Stefanos Kasselakis as their leader, U.S. educated, formerly a registered U.S. Republican (!), and a former banker who has written in favor of supply-side economics. So much for Socialism!

In my view, left-wing economic promises are only viable if the productive economy can actually bear the burden. Today, the United States for example has much more leeway in this respect than do most (southern) European countries. Some populist governments totally destroy their economies in this way, as in Venezuela, and can only further cling to power through authoritarian subversion of the democratic process.

By contrast, populists elected on economic promises that depend on them and are doable are more credible electorally, whatever their effects. Trump promised tariffs against China and he imposed tariffs on China, creating effectively a new consensus in the American political class (the tariffs were maintained and in some places toughened by President Joe Biden). It is too early to say how President Javier Milei of Argentina, elected on libertarian economic promises of abolition of whole government ministries and of crushing inflation, will fare, but I suspect his voters have been primed for the need for “tough love” and thus will be less likely to be disappointed.

2. Keep the vibe going

Populism is a vibe, as the kids say, a feel or a state of mind. The content of populist movements tends to be underdetermined. Many are relatively non-ideological in the sense of being known for a single mercurial and charismatic personality and a couple of signature issues—whether redistribution, protectionism, isolationism, anti-immigration, direct democracy, anti-vax, or whatever—but otherwise not having a well-defined broader agenda besides being the people’s eff-you to the establishment.

Outside of a populist movement’s signature issues, the messaging almost doesn’t matter as it is completely inaudible. This underdetermined quality makes populist parties often worth engaging with for other stakeholders: they can often be convinced of different points of view on issues other than their signature ones. It can also make populist movements politically nimble and able to surprise with new positions, adapting to new circumstances. But it can also mean a simple lack of a clear governing agenda, which can spell trouble when campaign rhetoric has to give way to a coherent approach and narrative in government.

Trump’s movement is emblematic in all these respects. The GOP’s new campaign platform is short, committed to a few strong positions on illegal immigration, protectionism, and unleashing fossil energy, but lacks specifics on many other issues. Trump’s coalition includes evangelical Christians, even though his personal mores are hardly very “traditional.” Consider Trump’s answer to a question from a supporter about his relationship with God and prayer:

I think it’s good. I do very well with the evangelicals. I love the evangelicals. And I have more people saying they pray for me—I can’t even believe it. And they are so committed and they’re so believing… It’s such a beautiful thing… Religion is such a great thing… There’s something to be good about. You want to be good… You want to go to heaven, okay. You want to go to heaven. If you don’t have heaven, you almost say: What’s the reason? Why do I have to be good? Let’s not be good, what difference does it make?

You might think this kind of answer would hurt Trump with evangelicals, but it doesn’t. It’s totally inaudible. Trump’s vibe, very much linked to his signature issues, eff-you personality, and comedy routines, overwhelms any possible off-messaging.

In 2016, while Americans voted for Donald Trump, the British voted to leave the European Union (Brexit). Brexit had no vibe. It was an accidental revolution, answering populist demands at the instigation of an establishment party, and unwillingly implemented by said establishment. Once the hapless Theresa May was out, Boris Johnson could have led a populist revolution, but he had no agenda to speak of and had trouble with establishment rules. Rishi Sunak took over and stoically led the Tories to electoral oblivion.

Prime Minister Georgia Meloni of Italy, of the right-wing nationalist Brothers of Italy (Fratelli), provides another example of the primacy of vibe over policy. Rhetorically, Meloni condemns globalists and liberalism much as other nationalist leaders do. In terms of policy, she has been extraordinarily mainstream and I couldn’t even tell you what her signature issues are.

Unlike Salvini, Meloni has not used her power to stop illegal immigration (possibly she is afraid of getting into legal troubles for this, as Salvini has been). In fact she has encouraged labor immigration of 450,000 people to work in agriculture, tourism, and construction. Her government has moved to preemptively ban lab-grown meat, ban English words in official correspondence, use the €18.5 billion allocated to Italy under the EU’s post-COVID recovery program, and otherwise not rock the boat.

Given Italy’s catastrophic economic situation, there is a case for taking the time to grow the economy and work down the country’s debilitating debt, necessary prerequisites to making the national government immune to adverse economic reactions from international markets and the EU institutions.

In any event, the Italians don’t seem to mind. While Meloni’s personal popularity is down from 54% when she took office in October 2022 to 45% today, that is hardly unusual. Support for her party is practically completely stable, if not a bit higher than when she took office. I would imagine she may need to take a stand on some populist signature issue(s) at some point, but so far even that hasn’t been needed.

3. Don’t overreach the Deep State

Populists must walk a fine line. On the one hand, their whole appeal is based on railing against the current cozy establishment of their country and addressing grievances—such as immigration, the decimation of the working class, or the spread of wokeness—that the existing political class has ignored. On the other hand, if populists excessively “spook” the existing establishment—meaning the current ruling political parties, media, courts, security agencies, and so on—these actors will take the gloves off.

History is full of examples of democratically-elected leaders and movements which were eliminated by military coup, in the name democracy, capitalism, the rule of law, secularism, or whatever. Salvador Allende of Chile, Abdelkader Hachani of Algeria, Necmettin Erbakan of Turkey, and Mohamed Morsi of Egypt are just a few examples of such leaders who were removed by their national Deep State, often with the backing of Western governments.

Admittedly, outright military coups are not the standard modus operandi in Western politics, but similar fears have led to measures such as the cordon sanitaire (the systematic political exclusion of parties considered unacceptable by the mainstream parties), media blackouts, surveillance and/or sabotage by security services, or outright bans in some cases (notably Germany and Greece).

I am not making a comment on the rightness or wrongness of said interventions. The point is every country has an establishment and a Deep State, which are committed to upholding certain norms, values, and interests as they see them. Unless populists plan on becoming revolutionaries—a risky approach which most often ends badly—then these need to gradually become acceptable to certain existing institutions. That does not necessarily mean selling out, but gradually reassuring and convincing a critical mass of existing players that one is a legitimate democratic political force and that addressing citizens’ longstanding concerns is not the end of the world. Populists need to be careful and strategic in walking this fine line as conditions differ greatly by time and country.

So can techno-populism work?

Overall, I think all this is bullish for Trumpian techno-populism. Populism tends to be emotive, mercurial, personality-driven, and predicated on conflict and lack of consensus within a country’s ruling class and society. None of this favors good government and political sustainability. However, populism disciplined by national business’ natural interest in economic stability and growth may be the most viable sort.

This isn’t to say that Trump has it in the bag this year. By jettisoning Biden for his deteriorating cognitive capacities and unifying around Vice President Kamala Harris, Democrats are massively improving their chances of victory in November. Nonetheless, I think the GOP’s refashioning itself in Trump’s image and the strong support from the Tech Right mean that Trumpism as a populist movement has a much better chance of being an enduring phenomenon, rather than a flash-in-the-pan destined to vanish with the inevitable end, soon or later, of Trump’s decade-long one-man-show.

One can regret populism but it is a natural outgrowth of democratic systems, especially as a certain conformity and standards can no longer be enforced by the mainstream media. The Internet, including social media and podcasts, have led to unprecedented media-political pluralism, for good and ill. It has also emerged as one of the only ways for marginalized segments of the public to voice grievances. Addressing those grievances would seem a simple way of preventing the rise of populist movements, as the Danish center-left has done by significantly reducing immigration. The Danish model does not seem likely to be replicated in other Western countries, so populism looks like it will continue to thrive and shake things up in various forms for the foreseeable future.

I’ll leave the final words to noted American littérateur H. L. Mencken.