Churchill’s Dream: An Anglosphere Union

With some lessons from a master communicator

I recently secured a copy of The Irrepressible Churchill, a book of Winston Churchill’s greatest quotes, jokes, put-downs, and “bangers” as the kids say, from the Chartwells bookstore in New York City. It was only when I got to the bookstore that I realized the store only contains books by or about Churchill. The store is certainly worth a visit if you have any interest in that area.

Reading Churchill is great for improving one’s style, both in writing and public speaking. The future prime minister made a living writing an astonishing array of books about colonial military conflicts, historical biography, and politics. Arthur Balfour called The World Crisis, Churchill’s book about World War I, “Winston’s brilliant autobiography, disguised as a history of the universe” (p. 70).

Churchill was a famously excellent communicator, able to convey even fairly technical political and military realities in evocative and down-to-earth language. He once explained his method: “I have often tried to set down the strategic truths I have comprehended in the form of simple anecdotes, and they rank this way in my mind” (p. 169).

Here are a few examples of Churchillian simile or analogy. On the power of battleships during World War I:

The offensive power of modern battleships is out of all proportion to their defensive power. … It is more like a battle between two egg-shells striking each other with hammers … The importance of hitting first, and hitting hardest and keepign on hitting … really needs no clearer proof. (p. 60)

On the logic of nuclear deterrence during the early Cold War:

The argument is now put forward that we must never use the atomic bomb until, or unless, it has been used against us first. In other words, you must never fire until you have been shot dead. That seems to me a silly thing to say, and a still more imprudent position to adopt. (p. 250)

On the postwar Labour government’s economic policies:

Why should queues become a permanent, continuous feature of our life? Here you see clearly what is in their minds. The Socialist dream is not longer Utopia but Queuetopia. (p. 247)

And so on. Churchill was also brilliant at ironic self-deprecation and responding to criticism with the “agree and amplify” technique:

Hitler in one of his recent discourses declared that the fight was between those who have been through the Adolf-Hitler schools and those who have been to Eton. Hitler has forgotten Harrow! (p. 146; Churchill had gone to Harrow, not Eton)

Churchill is also great at affirming the supreme value of a thing while acknowledging people’s very real frustrations:

There is only one thing worse than fighting with allies, and that is fighting without them. (p. 133)

Democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time. (p. 236)

Defending the League of Nations and international law:

Hypocrisy, it is said, is the tribute which vice pays to virtue. … I say frankly I would rather a peace-keeping hypocrisy than straightforward, brazen vice, taking the form of unlimited war. (p. 113)

Where there is a great deal of free speech there is always a certain amount of foolish speech. (p. 274)

Churchill was so known for his bons mots that he has also attracted sayings to himself that he apparently did not say, such as:

Americans can always be counted on to do the right thing, after they have exhausted all other possibilities. (This one is popular with U.S. politicians.)

To jaw-jaw is better than to war-war.

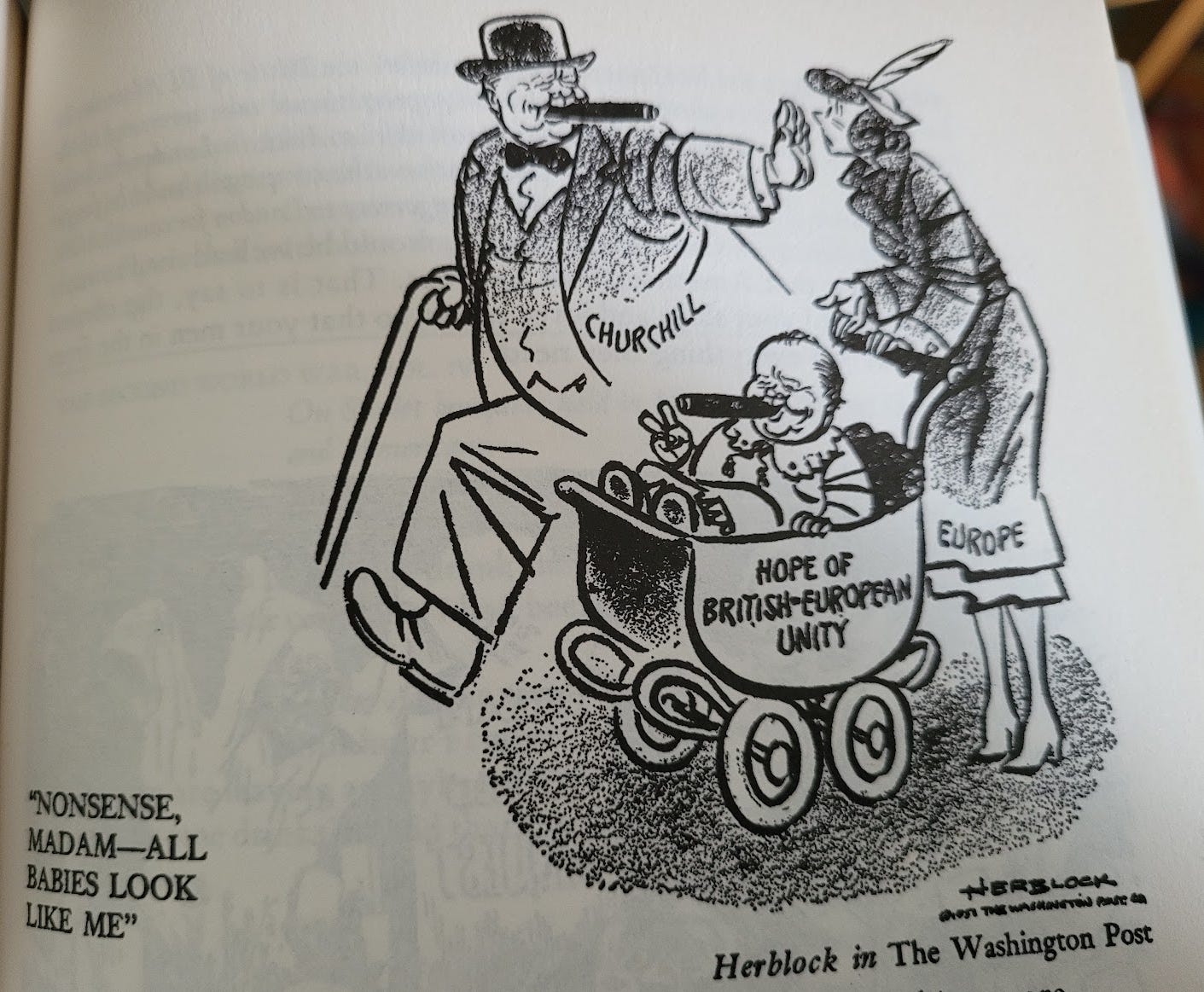

After World War II, Churchill popularized the term “Iron Curtain” for the Cold-War division of Europe and galvanized the European federalist movement by calling for “a kind of United States of Europe.” Certainly, “a kind of” is doing a lot of work in that sentence and Churchill didn’t want Britain participating in the European federation he called for.

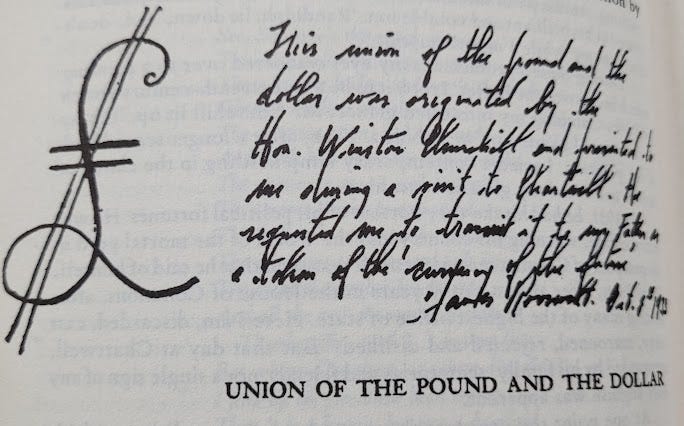

While obviously Churchill was pro-American (and his mother was a New Yorker), I did not realize before reading the book the sheer extent to which he was an Americanophile, to not say Americanomaniac. In October 1933, Churchill told James Roosevelt, son of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, of his fondest wish for the future:

I wish to be Prime Minister and in close and daily communication by telephone with the President of the United States. There is nothing we could not do if we were together. (p. 6)

Churchill then scribbled his vision of “the Dollar Sterling,” an Anglo-American common currency. He told James to tell his father “this must be the currency of the future.”

These atonishing declarations were not a one-off. A decade later, in May 1943, during a visit to the British Embassy in Washington, Churchill proposed common citizenship and free movement of people between the United States and the British Commonwealth:

I could see small hope for the world unless the United States and the British Commonwealth worked together in fraternal association. … I should like the citizens of each, without losing their present nationality, to be able to come and settle and trade with freedom and equal rights in the territory of the other. There might be a common passport or a special form of passport or visa. There might even be some common form of citizenship, under which citizens of the United States and of the British Commonwealth might enjoy voting privileges after residential qualification and be eligible for public office in the territories of the other… (p. 7)

The proposal sounds not unlike the kind of common citizenship and free movement now enjoyed by citizens of the nations of the European Union.

In 1946, he told some American colleagues:

W.S.C.: If I were to be born again, there is one country of which I would want to be a citizen. There is one country where a man knows he has an unbounded future.

Q: Which?

W.S.C.: The USA, even though I deplore some of your customs.

Q: Which, for instance?

W.S.C.: You stop drinking with your meals. (p. 223)

The exchange suggests, in typically joking fashion, that Churchill was not uncritical of America and he could be quite perceptive as to what made the nation tick:

The bigger the Idea the more wholeheartedly and obstinately do they throw themselves into making it a success. It is an admirable characteristic—provided the Idea is good. (p. 163)

Churchill could also be a ferocious critic of Wilsonian foreign policy, Americans not realizing how their exporting of liberal democracy and national self-determination could lead to catastrophic instability, imbalance, and blowback. As he wrote in a memo to the Foreign Office in 1941:

This war [World War II] would never have come unless, under American and modernizing pressure, we had driven the Hapsburgs out of Austria and Hungary and the Hohenzollerns out of Germany. By making these vacuums we gave the opening for the Hitlerite monster to crawl out of its sewer on to the vacant thrones. No doubt these views are very unfashionable… (p. 150)

All the same, Churchill decidedly sided with America and could see that its prospects were very bright for the foreseeable future. In August 1941, Churchill and FDR endorsed together the Atlantic Charter, which pledged to “respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they live; and … wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them.” This amounted to a death warrant for the British Empire and indeed all the European colonial empires. No doubt Churchill could see the writing was on the wall, though he always said he had fought for the British Empire and hoped for it (or the Commonwealth) to endure for a thousand years.

The Dollar Sterling and Anglosphere Union never saw the light of day; though I understand travel between Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States is usually quite easy, and these countries collaborate on intelligence within the unique Five Eyes alliance. Brexit having extricated Britain from the EU—though not in fact from the need for and reality of regulatory alignment in many economic areas—there has been talk of boosting Anglosphere cooperation. Most of it has remained just talk, although prospects for Anglosphere unity are perhaps the strongest they’ve been in decades.

I cannot resist concluding with a few more Churchillian bangers. When asked whether Roosevelt, Stalin, or Mussolini was greatest:

Of them all, Mussolini is the greatest. He had the courage to have his son-in-law shot! (p 201)

On his opposition to the use of AI in agriculture (artificial insemination):

The beasts will not be deprived—not while I’m alive! (p. 219)

On the advance of medical science (hits home for me as I now work a lot on health policy):

Fanned by the fierce winds of war, medical science and surgical art have advanced unceasingly, hand in hand. (p. 234)

I have been inclined to feel from time to time that there ought to be a hagiology of medical science and that we ought to have saints’ days to commemorate the great discoveries which have been made for all mankind, and perhaps for all time—or for whatever time may be left to us. Nature, like many of our modern statesmen, is prodigal of pain. I should like to find a day when we can take a holiday, a day of jubilation when we can fête good Saint Anaesthesia and chaste and pure Saint Antiseptic. (p. 234)

Some very good stuff here. I hadn't known he was this Americanophile either.

One interesting WW2 what if is an Anglo-French union in 1940, which almost came into being if not for France collapsing too quickly to properly consider it. Would it have fragmented post-war or would something permanent have come of it?