Did Denmark really curb immigration?

From outside of the West, mostly yes

Francis Fukuyama famously described the aspiration of modern nations as one of “getting to Denmark.” As he explained in his 2011 book The Origins of Political Order:

Denmark is a mythical place that is known to have good political and economic institutions: it is stable, democratic, peaceful, prosperous, inclusive, and has extremely low levels of political corruption.

Sadly, very few nations manage to “get to Denmark” in this sense. Every year, dozens of global indices of good government and national well-being are released in which Denmark and the other Nordics routinely dominate the top 10 (typically alongside Switzerland, Singapore, Canada, and such).

In recent years, literally getting to Denmark has gotten harder as a result of anti-immigration policies. In 2019, the country’s Social Democrats won parliamentary elections on an anti-immigration platform. Because the new policies were instituted by the center-left, this established a new national consensus and immigration seems a much less divisive political issue in Denmark than almost anywhere else in the West. In a recent Eurobarometer poll, only 7% of Danes said immigration was “one of the two most important issues facing our country,” as against 16% among EU citizens as whole (the third most important issue, after inflation/cost of living and the economic situation).

Abroad, the Danish Social Democrats have been both criticized for embracing the policies of the “far-right” and cited as a possible model.

But is Denmark’s anti-immigration turn even real? Often in politics, an issue can be massively overstated by both opponents and supporters. Denmark’s headline figures show only a small and short-lived reduction of immigration after 2019, and then a considerable increase:

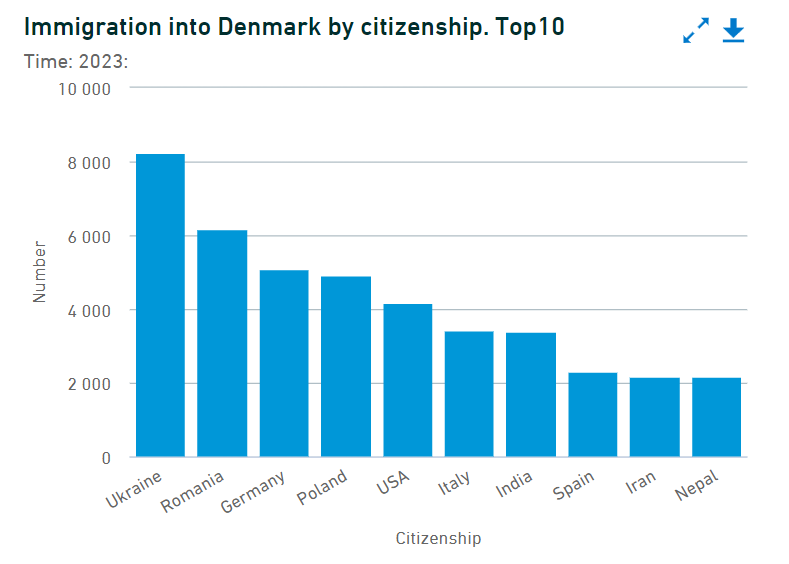

Perhaps the most important impact of Social Democrats’ anti-immigration turn has been on the sources of immigrations. It is remarkable that most of the top sources of immigration to Denmark are now Western or European. This includes both EU migrants (from Italy, Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain…) which Denmark, as an EU member state, is not allowed to refuse entry to, and a more recent spike in Ukrainian refugees as a result of Russia’s invasion.

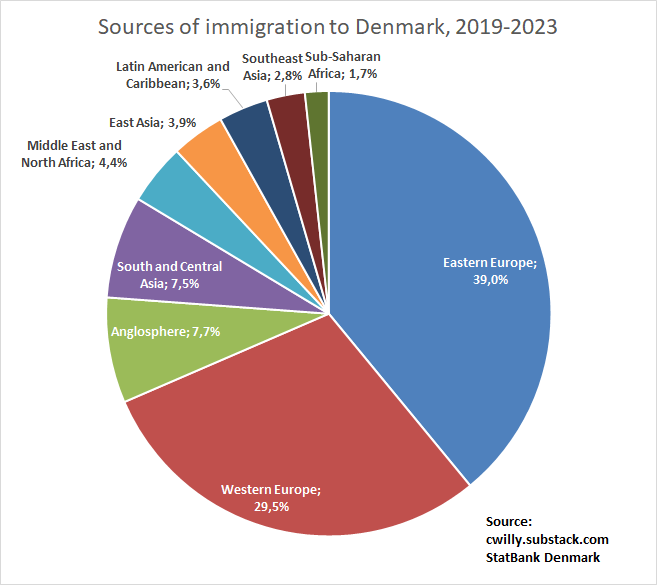

I crunched the numbers to get more precise figures over time, assigning all countries to different regions:

We see that, from a peak during the 2015 migrant crisis, immigration from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) was already decreasing, but also that there has been no major increase from that region since the anti-immigration reforms of 2019.

According to official figures, 350,000 people have immigrated to Denmark in the five years between 2019 and 2023, or equivalent to 6% of the population (note there have also been 226,000 emigrants away from Denmark over the same period, on which we have less information, but 72% were not Danish citizens). If we add up all the immigrants by region for 2019-2023, we get the following proportions:

Cumulatively, over 75% of immigration to Denmark is of Western or European origin, and 6.1% of Middle Eastern or African origin. This is a very different migratory pattern than what we see in most other Western European countries. In France for example, over half of all immigrants come from Africa or Turkey, and only a third come from Europe.

Denmark is still an immigration society. A permanent influx equivalent to 0.5-1% of population every year will have a transformative impact over time. However, because of Danish political choices, the country’s population will remain largely Western and European in origin.

The Danish political class has been strikingly responsive to voters on this issue. Many Danes are concerned about the spread of Islam in their society, with high-profile controversies over cartoons featuring the prophet Muhammed (which prefigured the more recent mass murder of blasphemous Charlie Hebdo cartoonists in France). Eurobarometer polls have found that Europeans generally feel significantly more positively about European immigrants than non-European immigrants. This is no doubt in part because of the relative ease of assimilation of Western/European immigrants and fears about the rise of ethnic/Islamic “parallel societies.”

What’s more, as The Economist has pointed out, immigrants to Denmark from the Middle East and North Africa have an overwhelmingly negative net fiscal impact, reflecting less contributions in terms of taxes and more consumption of public services.

In addition, non-Western immigrants and their descendants account for a massively disproportionate share of violent crime convictions in Denmark. Pointing out this fact may be upsetting to some in polite society but physical security is of fundamental interest to the citizens of the recipient nation and many voters care deeply about.

Overall, Denmark shows that immigration flows can indeed be reduced and reshaped according to the preferences and interests of the people, if the government is willing.

The Danish approach to immigration is certainly distinctly soft compared to many non-Western countries. Immigration to Denmark is very high compared to that towards wealthy East Asian countries such as South Korea and Japan. Among the Gulf Arab states, immigration levels are very high, but these immigrants are simply point-blank denied the possibility of ever acquiring citizenship. Israel has an immigration policy explicitly aimed at strengthening the Jewish majority, while Singapore tailors migration to maintain the existing “racial balance” within the country (which in practice means trying to maintain the low-fertility Chinese’s super-majority around 75%). Denmark, like the rest of the West, remains remarkably open to immigration by global standards.

The case of Denmark is all the more remarkable in that an anti-immigration turn among by center-left parties in most other Western countries would seem impossible. While there are anti-immigration left-wing traditions, embodied in figures like Jack London or Georges Marchais, most left-wing parties in the West today find opposition to immigration to be anathema.

Left-wing parties’ reluctance to oppose immigration has various motives, such as the need to appeal to new immigrant-origin ethnic constituencies, left-wing commitments to universalism and openness, and the self-radicalization (“wokism”) of left-wing parties due to generational change and the rise of left-wing echo chambers. As former Bill Clinton adviser James Carville has noted, the rise of woke purity spirals within the Democratic Party threatens its ability to appeal to moderate and less politicized voters. It seems that in terms of consensus on immigration policy too, few places will be getting to Denmark any time soon.

Japan's immigration laws are actually softer than America's for skilled workers. They just happen to have low levels of immigration because fewer people want to come, and many who do come decide not to stay because the language and customs are difficult. In Japan it's not so much policy that is responsible for low levels of foreign migration but rather social barriers and other disincentives (work culture, isolation, limited space, etc)

Taiwan's immigration system is quite open. It's similar to Canada or Australia in terms of ease of immigration, and the government is pro-multiculturalism. But their percentage of immigrants remains quite small

"Israel has an immigration policy explicitly aimed at strengthening the Jewish majority,"

Yes in a broad sense but No in a narrow sense. In a broad sense, one can indeed argue that most immigrants to Israel are a part of the enlarged Jewish family. In a narrow sense, however, it is worth pointing out that most immigrants to Israel are not halakhically Jewish.

The issue that I see here, is that while in Europe I'd very much be a restrictionist towards Muslims and Africans, I really don't feel all too negatively about Latin Americans coming to the US in huge numbers and indeed think that we should compensate for this by accepting many more global cognitive elites, not by making immigration to the US much harder for Latin Americans.