Do we need Carl Schmitt?

Groping for alternatives to liberalism and autocracy

Carl Schmitt—the onetime-Nazi German legal theorist—has been receiving increased attention in recent times. Economic historian Phil Magness has pointed out how Schmitt is a popular namedrop among American “post-liberals” today. Commentator Richard Hanania has pledged: “Having seen that he is by far the favorite thinker of the stupidest people on X, I’ve decided to start reading Carl Schmitt. Will report back.”

One doesn’t need to be a Nazi or even a right-winger to engage with Schmitt’s thought. His work is a fairly popular subject of study in academia, particularly among critics of liberalism, including left-wing critics. For instance, Oxford University Press released an 874-page Handbook of Carl Schmitt a few yearsback. “Carl Schmitt” yields 154,000 hits on Google Scholar, as against 179,000 for “Noam Chomsky” or 585,000 for “Hannah Arendt.” So he is a definitely a thinker that scholars engage with.

I can’t claim to understand the whole (alleged) profundity of Carl Schmitt’s political thought, but I have read some of his (rather dense) work and have a sense of “the popular Carl Schmitt,” i.e. how Schmitt is actually used by political activists today.

People generally retain two major concepts in Schmitt’s thought:

The friend-enemy distinction: For Schmitt, efforts to neutralize politics through procedure or democratic norms are futile. The essence of “the political” is the irreducible conflict between the political order’s friends (“us”) and its enemies. Once enmity becomes existentially threatening to a political order, normal rules and conventional morality are typically suspended until enemies are neutralized. Liberalism can at best only mask this reality of existential conflict.

The sovereign and the state of exception: For Schmitt, a political order’s real sovereign is whoever “decides on the exception” when ordinary rules are suspended. For him, such episodes—which are common enough during war, crises, and other emergencies—are not just a temporary divergence from regular procedure, but can be moments of “constituent power,” when a regime’s fundamental constitutional order is reformed. This reform does not follow regular legal procedure, but necessarily exceptional sovereign power.

Schmitt seems to reveal the dark, power-political underbelly of liberalism. Sure, it may seem to be about neutral procedures and universal rights, but when push comes to shove, politics is (legitimately and inevitably) about force: some winning, others losing, through exclusion and if necessary through violence. Liberals may try to dress things up in moral or legal terms, but in the key moments, that is what politics is about.

There is something to this, though I don’t know how original these insights are. At the least, liberal philosophers as far back as John Locke have acknowledged that exceptional executive power can be necessary in times of crisis and that use of such power is necessarily chancy.

Schmitt’s friend-enemy distinction perhaps does give us a sense of the intolerance that (necessarily?) accompanies the foundation of political orders, including liberal ones. The American Revolution led to the ostracism and persecution of Loyalists, with up to 100,000 people fleeing the newly-formed USA (most of them to Canada). Similar observations could be said of the U.S. after the Civil War, the Liberation of France during World War II, or indeed the day-to-day operation of the Federal Republic of Germany, whose judicial system is always debating which political groups need to be banned, spied upon, or otherwise restricted from participating in democratic life.

There is also something to Schmitt’s account of the state of exception and regime reform. According to the old Roman republican ideal, a virtuous leader like Cincinnatus might be appointed temporary dictator with emergency powers for the time of a crisis, on the understanding that he would later retire and restore the old system. In practice, leaders wielding emergency powers often do not simply bend or suspend the rules, but fundamentally and permanently change the underlying system.

Abraham Lincoln conducted the Civil War, suspended habeas corpus, and emancipated slaves in the Confederacy on the understanding that such actions were needed to preserve the Union and safeguard the Constitution. Lincoln’s rhetorical and intellectual commitment to the Constitution was tremendous. But as historians like Eric Foner have argued, the Civil War did not simply restore the Constitution but was a “second founding” that fundamentally changed the U.S. regime. This process was formalized in the Reconstruction amendments, notably empowering Congress to enforce civil rights in the states. The passage of these amendments was arguably coercive, with the Fourteenth Amendment in particular adopted during military occupation of the Southern states, with state ratification of the amendment being made a condition for regaining representation in Congress.

A more recent example of sovereign power is offered by the Eurozone Crisis. Within the European Union, monetary policy is arguably the only area where core “regalian” sovereign state power has been federalized, in the hands of the European Central Bank (ECB). During the crisis, when international investors refused to lend further to finance government deficits in indebted countries, ECB Presidents Jean-Claude Trichet and Mario Draghi became something like Schmittian sovereigns.

By conditioning its financing of national banking systems, the ECB could control or topple the governments of Ireland, Greece, or even Italy. The ECB also conditioned a looser monetary policy on reform of the Eurozone’s fiscal rules to better enforce deficit limits. Once these were in place, President Draghi was able to calm financial markets by famously declaring:

Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.

Thus the ECB used its sovereign monetary power not only episodically, but to permanently change the Eurozone’s macroeconomic “constitution.”

Schmitt seems to overstate the sovereign’s reform power in constitutional regimes. Lincoln and Draghi did wield exceptional powers, but neither was alone in changing the nature of their respective systems. Certainly, the use of exceptional power creates “facts on the ground” which can heavily distort procedures or simply impose material changes, but all the same these procedures are not wholly meaningless and certainly cannot be reduced to the will of the executive.

Schmitt will always be tainted by his association with the Nazi regime and his notorious defense of the Night of the Long Knives with an article entitled “The Führer Protects the Law.” Ironically, prior to 1932, he advocated that Weimar Republic’s presidency use its exceptional powers to overcome parliamentary impotence and exclude Nazis and Communists from power. In that sense, I would say there is nothing inherently Nazi about Schmitt’s thought. In fact, from 1936 Schmitt became marginalized within the Third Reich, as he was criticized for being an opportunist whose thought was not really grounded in Nazism. Schmitt as an authoritarian Catholic seems more in tune with the conservative, steady dictatorship of António Salzar in Portugal than the hysterical racial nationalism of the Third Reich.

As far as I know, Schmitt has little to say on how to prevent abuse of power by the executive or how to create an actually functioning legal order after the state of exception. Whatever the need for executive power in crises, the rule of law is superior in predictability and regularity to permanent executive autocracy, with its inevitable caprice and abuse (both in terms of corruption and of suppression of truth-telling). In my view, a good regime is flexible enough to wield necessary power in crisis, to some extent to change nature in crisis, but ultimately to revert to a regular legal order, however imperfect in day-to-day operation.

What of “popular Schmittians” today? For the most part, Schmitt seems cited by political activists mainly as advocacy for ad hoc autocracy: that “our” government leaders need to be realist, hard-headed, and thus do away with procedures and persecute the libs. After all, beneath the veil of the rule of law, the libs are just persecuting you in accordance with the friend-enemy distinction. I don’t know that there is anything more to it than that. One ought only to trust the sovereign dictator: After all, he and I are part of “us,” are we not?

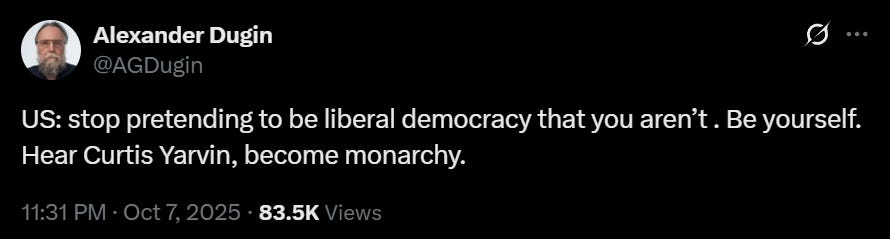

Case in point:

Indefinite and unlimited sovereign autocracy—particularly in large autarkic nations—has disadvantages too numerous and obvious to mention. This obviously isn’t very helpful, even for good-faith attempts to develop viable positive alternatives to contemporary liberalism, which after all is showing many signs of breaking down. If you think any popular Schmittians have made thoughtful attempts at articulating such alternatives, do point their work my way.

“We elect a king for four years and give him absolute power within certain limits which, after all, he can interpret for himself”. Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Henry Seward.

> beneath the veil of the rule of law, the libs are just persecuting you in accordance with the friend-enemy distinction

The term "rule of judges" better captures underlying reality than "rule of law," and Schimitt's insights are just as applicable to rule of judges as they are to autocracy:

1. The antithesis of the friend-enemy distinction is equality before the law, and it has rarely if ever been upheld. For example, courts routinely treat protests accompanied by some disorder & law-breaking differently depending on protester's political message

2. Courts frequently act as sovereign, in a same sense as ECB has. When judges unilaterally deem the political or moral order threatened, they adjudicate cases as exceptions by circumventing standard judicial practices & traditions. Such rulings establish precedents that permanently reshape the legal order.