Europe’s Evitable Dependence on Big Tech

Why Europe Needs an Airbus for AI

Dependency Theory is the idea that wealthy countries keep other economies in a permanent state of underdevelopment. According to this idea, advanced industries and nations “kick the ladder” after them, preventing others from catching up and maintaining them in dependence.

For the most part, I think Dependency Theory is false. In many sectors, less developed countries can use their comparative advantages (especially lower-wage labor) to outcompete their more developed peers. The story of Western economies since the 1970s is in no small part one of one industry after another being shifted abroad, especially to East Asia. Today, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore have roughly equal or even superior standards of living to many Western countries.

There is one sector however where Dependency Theory seems accurate: Big Tech. In his book Zero to One, tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel is emphatic on the unforgivingly winner-take-all dynamics of so many tech sectors. Especially, the economies of scale and network effects of many tech sectors—the fact that using a social media, operating system, or payment platform is valuable to the extent that others are also using it—makes for massive tendencies towards concentration and monopoly.

This is the basic self-reinforcing mechanism behind the success of les GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft), Twitter, PayPal, and many other Silicon Valley success stories. Indeed, when he wrote Zero to One, Thiel said he was only interested in investing in firms with that kind of transformative and monopolistic potential; capable of becoming “the kind of company that’s so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute.”

The result of this is that Europe is kept in a permanent state of dependence relative to U.S. tech giants. It isn’t that Europeans are incapable of doing tech. In the 1980s, prior to the World Wide Web, the most successful online service in the world was France’s Minitel, which provided services such as phone directory, mail order, and train ticket purchases.

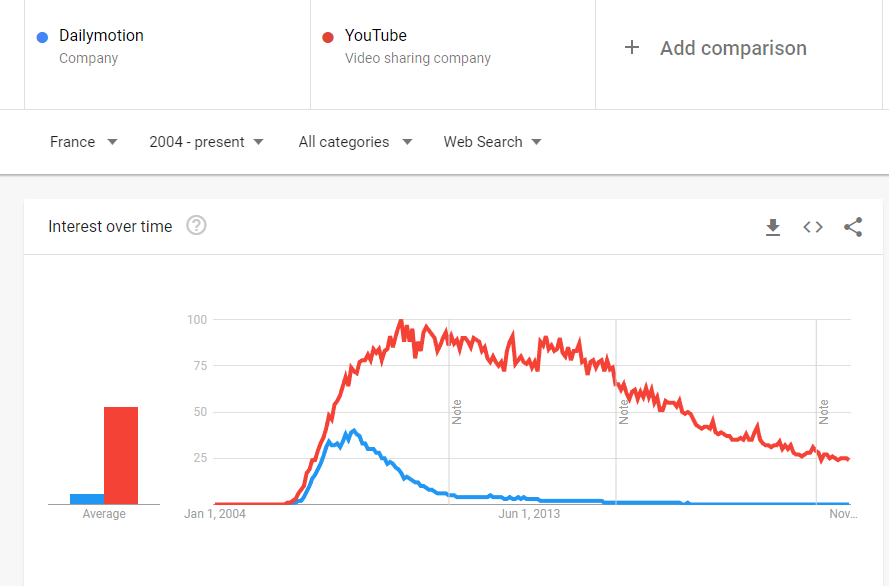

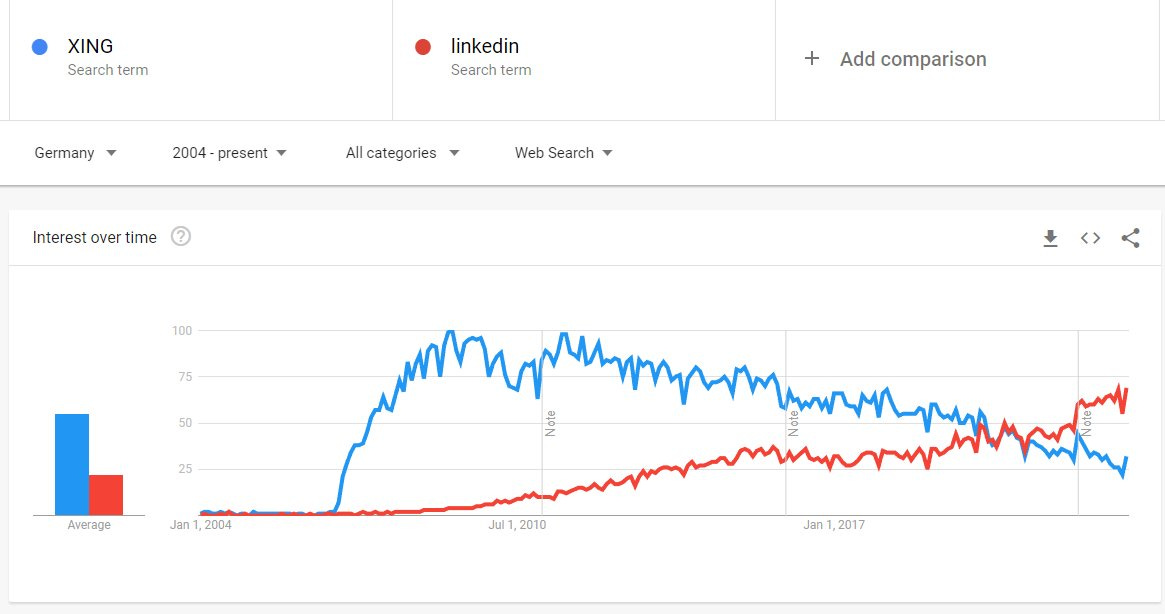

For just about every leading American social media, there has been a (temporarily) successful European equivalent. In France, there is the video-streaming service DailyMotion; in Germany, the professional social network XING; in Spain, the regular social network tuenti. For a time, each of these was nationally competitive with their Silicon Valley equivalent or even outright dominated their national market. Consider these Google searches over time:

The problem is that the European digital market is too fragmented—for social media the barriers are as much memetic (socio-cultural and linguistic) as legal—and the national markets are too small. Eventually, the Silicon Valley equivalent, empowered by the profits and network effects of America and other markets, naturally overwhelms the national alternative. It has gotten to the point where incumbent American tech giants simply hoover up any promising European startups—e.g. Skype, made in Estonia, was bought by Microsoft. Spotify is a rare exception, being still controlled by its Swedish founders, Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon.

More than America’s entrepreneurial drive or even the deep pockets of its venture capital funds, it is the combination of Europe’s fragmentation and openness that has led to its dependence on American Big Tech. By contrast, China, Russia, and even Iran have been able to develop their own Internet ecosystems, with varying degrees of success, through protectionism and/or scale.

Big Tech has become another major attribute of the American superpower, alongside its more traditional economic, military, diplomatic, and cultural dimensions. The United States derives numerous advantages from hosting Big Tech: in terms of its economy and finances, technology, intelligence (spying, big data), and soft-power (control of information flow, censorship). Europe suffers symmetrical disadvantages. Edward Snowden’s revelation back in 2013 of massive spying by the U.S. government on European citizens, including heads of state and government, is only the most visible example. Not a day goes by without some negotiation, compromise, or struggle between Silicon Valley and the EU institutions and national capitals.

The European Union and several national governments, not least France, are making major efforts to restore Europe’s digital sovereignty. There are three basic approaches to doing this.

The first is to restrict foreign tech companies’ activities in the EU market. Realistically, this will likely primarily target Chinese and Russian companies.

The second is to regulate tech to respect European values and interests. This is the EU’s favorite approach. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the best-known example of this, but there are others such as the Data Act and Digital Services Act. Because of the size of the EU market—its GDP of $16.6 trillion still accounts for a sixth of the global economy—and the European Commission’s ability to inflict massive fines, tech companies are usually willing to make a major effort to comply with EU rules. When Elon Musk took over Twitter, the European commissioner responsible for tech regulation, the Frenchman Thierry Breton, boasted:

What EU regulation means in practice however is often not so clear. Precisely on the Musk-Twitter affair, French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted that EU rules mean Twitter must have “significant reinforcement of content moderation and protection of freedom of speech.” A classic en même temps moment. Obviously, one person’s free speech is another person’s lack of content moderation, while one person’s content moderation is another person’s censorship.

GDPR is another example of how confusing EU regulation can be. The law is notoriously complex, to not say waffly—I once heard a law professor describe it saying, “In it, the rule is the exception.” (Meaning, for every rule, there are huge exceptions.) Certainly, it is a rare European citizen who can tell you how they are empowered or protected by these regulations.

A variant of this regulatory approach to tech sovereignty is to jointly regulate tech with the United States. If Brussels and Washington are able to set transatlantic standards, these are almost certain to become global standards, certainly outside of the Russo-Chinese sphere. Since the Biden Administration came into office, the European Union and the United States have set up a Trade and Technology Council (TTC) with precisely this goal, although so far it seems the results have been slim.

A final, third approach to tech sovereignty, the most difficult and arguably most interesting, is to develop Europe’s native digital capacities and tech prowess. The European Commission has also pushed forward in this area with a Chips Act which aims to mobilize €43 billion in investments and double the EU’s share in semiconductor manufacturing to 20% by 2030. The Commission has also pushed to develop business alliances to strengthen Europe’s cloud computing capacities.

The impact of these various approaches and initiatives remains to be seen. Two things are clear however:

The digital playing field is not “level” (a favorite EU term for fair competition).

Digital is eminently strategic, with tremendous economic, telecoms, technological, intelligence, and even cultural implications for national and European sovereignty.

Now, with the emergence of artificial intelligence, digital will be more strategic than ever: nations with a decisive lead in AI could achieve general preeminence over others, especially if the tech advance becomes self-reinforcing (for example, if AI becomes so advanced as to become capable of continuously improving itself).

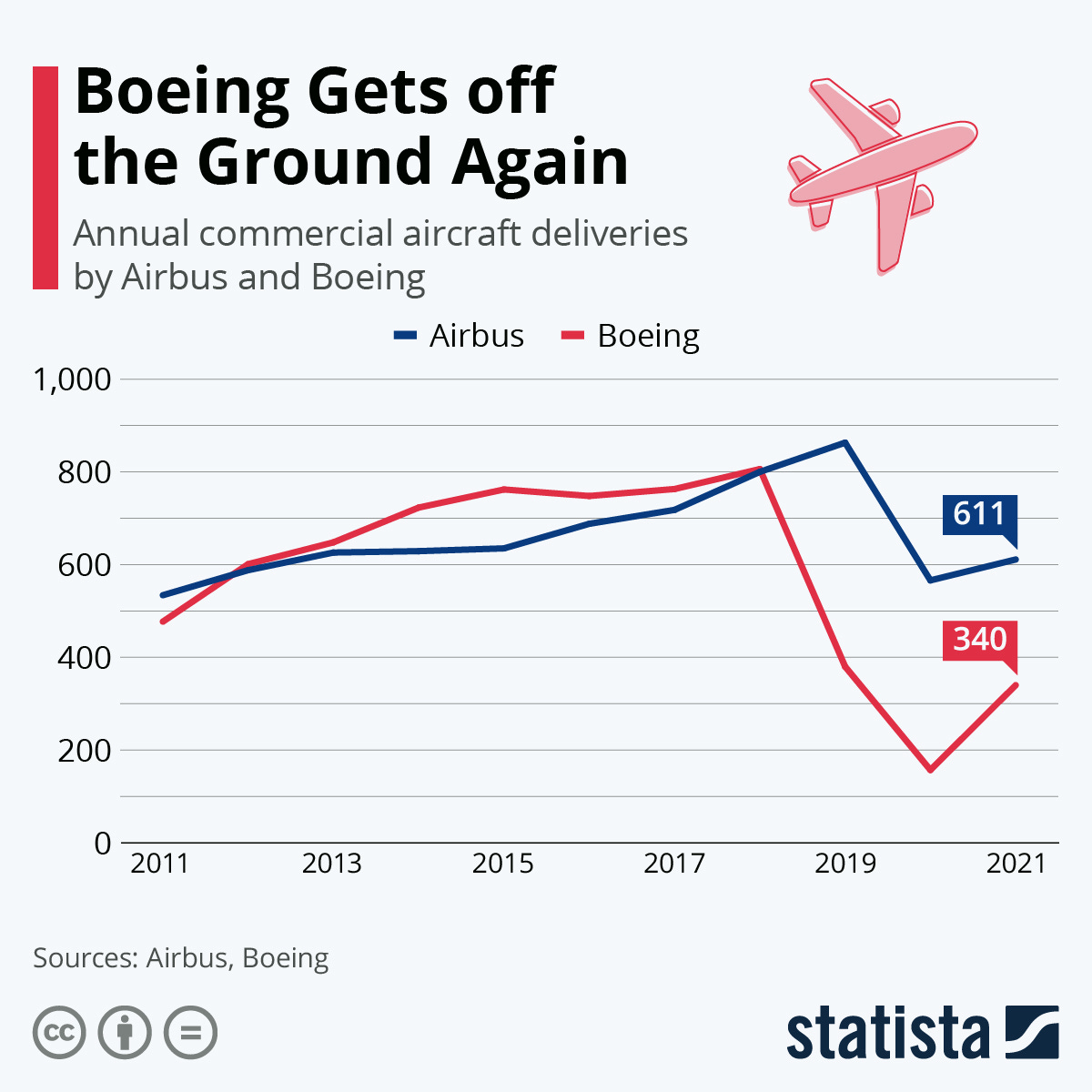

This isn’t the first time Europe has been cripplingly behind in a strategic industry. In the 1960s and early 70s, the manufacture and sale of large commercial aircraft was dominated worldwide by just three companies, all of them American: Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, and Lockheed. Europe did not exist.

In 1970, one French and one German aerospace firm came together to rectify the situation by creating Airbus as a European aerospace company with the scale to compete with the Americans. Soon joined by a British and a Spanish company, Airbus was able to slowly but steadily challenge and eventually break the Americans’ total domination of the sector.

Lockheed exited the sector. McDonnell Douglas declined and was taken over by Boeing. Airbus would actually often surpass Boeing itself in sales and now the two effectively form the global duopoly for large commercial aircraft. Airbus has outsold Boeing for the last four years straight, dominating the Chinese market in particular.

Airbus has been a recurring source of transatlantic tensions over trade for decades. The Americans complained that European governments were giving unfair “launch aid” to Airbus to support it in the expensive and risky business of developing large aircraft for the market. The Europeans countered that Boeing had long received de facto subsidies from the U.S. government through massive defense contracts. Washington and Brussels sued each other before the World Trade Organization, which has found them both guilty on occasion.

Whatever one thinks, aerospace was and is a strategic sector for Europe, crucial to maintaining sovereignty in both military industry and space capabilities. Indeed, Airbus’ initial success in civil aircraft has enabled it to grow a wider business in defense, space, and helicopters, as well as a whole aerospace ecosystem of contractors, rockets, satellite operators, big data analyzers…

Airbus shows that Europe can regain the lead in an apparently lost industrial sector. Today, it would seem crucial to do so in digital and especially AI. Europe needs to build an Airbus for AI. The EU institutions as such should not lead such an effort—the logic of consensus among 27 member states and inter-institutional negotiation does not make for business sense—but rather a consortium of leading national tech firms. Paradoxically, the political need for a European AI champion is there but business should be in the lead. Remember Quaero?

"For the most part, I think Dependency Theory is false".

For the most part, C.W., I think it is true.

Examined here in The Decline of The West, as they cannot keep that showboat afloat any longer . . .

https://les7eb.substack.com

Tu devrais faire en sorte de rendre tes billets plus populaires, CW. Ca se tient.