Oliver Wendell Holmes, American Nietzschean

Richard Posner (ed.), The Essential Holmes (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1992)

Hail Amazon! Hail Jeff Bezos! Whatever their other deeds or misdeeds, thanks to their work, I am able to purchase at reasonable prices worthy books otherwise unavailable in Europe such as that above. While the book was originally published by University of Chicago Press, my copy was printed-upon-order by Amazon, as indicated on the last page, in “Brétigny-sur-Orge, FR.”

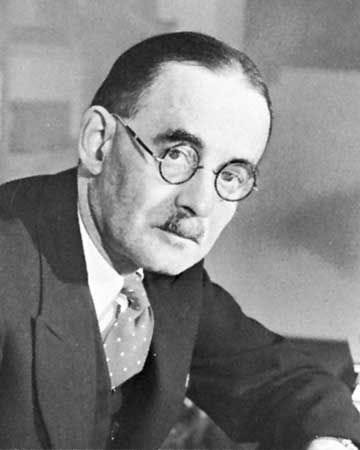

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1841-1935) was one of the most influential justices to have ever sat on the Supreme Court of the United States. In his rulings and especially in his dissents, Holmes expressed influential opinions, including defenses of free speech (defining the “clear and present danger” requirement for censorship) and broad freedom of the states to regulate (notably economic life).

It is striking that Holmes, from the highest judicial bench in the land and in private letters, expressed eloquent criticism of the kinds of over-generalizing slogans and moralistic rhetoric expressed by some of America’s founders, such as Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson. Holmes did not believe in eternal abstract rights—whether granted by some Creator or Reason—but rather in particular concrete rights necessarily reflecting the changing circumstances of different communities struggling for existence.

Holmes’ philosophy of life and law was profoundly influenced by two factors: his youthful experience as a Union solider in the Civil War (wounded three times) and the impact of Darwinian evolutionary science that permeated so much of Anglo-American thought until World War II.

The experience of the Civil War gave Holmes a depth often lacking in peacetime liberal thought: if conscription, self-sacrifice, and killing were justified to save the Union and abolish slavery, then there must be values greater than comfort, security, and indeed mere life. His acceptance of the necessity of war and coercion in certain circumstances also gives his thought a realist, power-political edge.

Holmes’ thought was Darwinian in seeing that all life, including human societies, is the product of a process of evolution resulting from innovation, struggle, and selection. For this reason, law had to be open to change and could not be, and in fact never was, merely logical deduction from axioms expressed at some time in the past. Holmes’ commitments to free speech (to enable a competitive “marketplace of ideas,” his expression), political pluralism, social experimentation (by the states and by private associations), capitalism, science, and eugenics can all be seen as part of the need as he saw it for America to always be a diverse, dynamic, experimental, and evolving society defined by novel practices and experiences, not speculative abstractions and ossified dogmas. Holmes even occasionally seems open to a downright futuristic upward evolution of the human species into something greater, and/or different, perhaps making him a precursor of transhumanism.

Holmes was a Nietzschean in seeing that the universe seemed to offer humanity no values other those they make for themselves. Conflict among human beings is inevitable insofar as these have irreconcilable differences of taste concerning ultimate values and ends. Perhaps the preeminent value for Holmes was the development and exertion of human beings’ individual and collective capabilities, including the capacity to intelligently articulate and refine one’s values through experience and reflection.

Richard Posner’s selections from Holmes’ includes letters to diverse intellectual figures, speeches, legal rulings and dissents, and academic articles, providing a fine survey of his maxims (rules for life), legal arguments, philosophy, and style.

Herewith are extracts from the book that I think are worth (re)discovering.

* * *

[L]ittle peoples and small populations have done things in their day and may again. [Ancient] Athens could not have kept New York going for ten days, I suppose, but it counts for more than the United States. Perhaps in the future we shall care less for quantity and more for quality and try to breed a race. (1912, p. 6)

On his wife Fanny Holmes’ death:

For sixty years she made life poetry for me and at 88 one must be ready for the end. (1929, p. 12)

It makes me think of the time when all life shall have perished from the earth, and tests the strength of the only comfort I know—the belief that the I-know-not-what [the universe], if it swamps all our human ultimates, does so because it is in some unimaginable way greater than they, which are only a part of it. But I also think that our demands for satisfaction [before death] are intensified by exaggeration of the belief in the unity of ourselves and a failure to see how they change in content and contour—as if natural if consciousness is only an electric illumination of cosmic currents when they make white light. (1929, p. 15)

Solitaire seems always an epitome of life. One says to oneself, why do I care whether I win the game or not, and then one answers, why do you care to live, or like beer (not that I ever drink it), or why do you work? I know no answers except that that’s the way I’m made. As Frenchwomen in novels frequently justify their foibles by generalizing, Je suis comme ça. One can take oneself solemnly or lightly. One has to be serious when at work. When at leisure one surmises that it will not matter much to the Cosmos whether one turns to the right or to the left, but one doesn’t know. [...] Having made up your mind that you are not God, don’t lie awake nights with cosmic worries. (1931, p. 17)

In a letter (1913) to Alice Stopford Green, an Irish historian and nationalist:

Naturally I don’t believe in the institution [the House of Lords] but individually a good many of them seem to me not bad specimens. Nature is an aristocrat or at least makes aristocrats, e.g. the cat—and one recognizes certain bloods that generation after generation turn out superior men with here and there a genius. But this is a platitude that I ought to apologize for uttering to you. … I suspect if I were an Englishman I should be against [Irish] home rule. You have taught me something of the wrongs that have been done [by the British], but I have not quite as much respect for abstract human rights as you have and I think the welfare of the Empire would outweigh all other considerations. I believe in the iniquitous doctrine of my country right or wrong. Don’t throw me over for my speculative wickedness. (p. 22)

I said of the [Theodore] Roosevelt movement that it seemed characterized by a strenuous vagueness that made an atmospheric disturbance but transmitted no message. To prick the sensitive points of the social consciousness when one ought to know that the suggestion of the cures is humbug, I think wicked. (1912, p. 28)

[I]f one can’t think about oneself a little as he reached 80, when can he? It makes me tired to read of the mellifluous days when it is to be all ꜱᴇʀᴠɪᴄᴇ—and love our neighbor and I know not what. There shall be one Philistine, egotist, unaltruistical desirer to do his damnedest, and believer that self, not brother, was the primary care entrusted to him, while this old soldier lives. If A lives for B and B for C and so on there must be an end somewhere. Let’s be End—you as well as I. ...

N. B.: I have always insisted that the above vaunted egotism makes us martyrs and altruists before we suspect it. (1921, p. 39)

I often say over to myself the verse “O God, be merciful to me a fool,” the fallacy of which to my mind (you won’t agree with me) is in the “me,” that it looks on man as a little God over against the universe, instead of as a cosmic ganglion, a momentary intersection of what humanly speaking we call streams of energy, such as gives white light at one point and the power of making syllogisms at another, but always an inseverable part of the unimaginable, in which we live and move and have our being, no more needing its mercy than my little toe needs mine. It would be well if the intelligent classes could forget the word sin and think less of being good. We learn how to behave as lawyers, soldiers, merchants, or whatnot by being them. Life, not the parson, teaches conduct. But I seem to be drooling moralities and will shut up…” (1926, p. 43)

I read Aristotle’s Ethics with some pleasure. The eternal, universal, wise, good man. He is much in advance of ordinary Christian morality with its slapdash universals (Never tell a lie. Sell all thou hast and give to the poor etc.) He has the ideals of altruism yet understands that life is painting a picture not doing a sum, that specific cases can’t be decided by general rules, and that everything is a question of degree… (1906, p. 58)

When you see a Roman gentleman praising a younger man man for letting his slaves eat with him and suggesting that he should look for the gentleman in them as they may see the slave in him and laying down the maxim, treat your inferiors as you would like your superiors to treat you, you begin to suspect that the lesson of cosmopolitan humanity came to the Christian churches from the Romans rather than to the Romans from the Christians. (1924, p. 59)

I have no a priori objection to socialism any more than to polygamy. Our public schools and our post office are socialist, and wherever it is thought to pay I have no objection except that it probably is wrongly thought. But on the other hand I have as little enthusiasm for it as I have for teetotalism. (1912, p. 65)

Speech at a meeting of Civil War veterans, 11 December 1887:

The list of ghosts grows long. The roster of men grows short. My memory of those stirring days [of the Civil War] has faded to a blurred dream. Only one thing has not changed. As I look into your eyes I feel as I always do that a great trial in your youth made you different—made all of us different from what we could have been without it. It made us feel the brotherhood of man. It made us citizens of the world and not of a little town. And best of all it made us believe in something else besides doing the best for ourselves and getting all the loaves and fishes we could. I hate to hear old soldiers tell what heroes they were. We did just what any other Americans—what the last generation would have done, what the next generation would if put in our place. But we had the good luck to learn a lesson early which has given a different feeling to life. We learned to believe that doing one’s duty is better than the loaves and fishes and that honor is better than a whole skin. To know that puts a kind of fire into a man’s heart, and there is nowhere a man learns it as he does in battle. Those who died there died, as a solider said hundreds of years ago, with a bird singing in their breast. Those of us who survive have heard the same music and through all the hard work of later years have remembered that once we listened to strains from a higher world. (pp. 73-74)

We all, the most unbelieving of us, walk by faith. We do our work and live our lives not merely to vent and realize our inner force, but with a blind and trembling hope that somehow the world will be a little better for our striving. Our faith must not be limited to our personal task; to the present, or even to the future. It must include the past and bring all, past, present, and future, into the unity of a continuous life. (1902, p. 74)

It is a question of the significance of the universe, when we do not know even whether that is only a human ultimate quite inadequate to the I-know-not-what of which we are a part. It is enough for us that it has intelligence and significance inside of it, for it has produced us, and that our manifest destiny is to do our damnedest because we want to and because we have to let off our superfluous energy just as the puppies you speak of have to chase their tales. … One of my old formulas is to be an enthusiast in the front part of your heart and ironical in the back. It is true that many people can’t do their best, or think they can’t, unless they are cocksure.

As long ago as when I was in the Army I realized the power that prejudice gives a man; but I don’t think it necessary to believe that the enemy is a knave in order to do one’s best to kill him. (1925, pp. 75-76)

The army taught me some great lessons—to be prepared for catastrophe—to endure being bored—and to know that however fine [a] fellow I thought myself in my usual routine there were other situations alongside and many more in which I was inferior to men that I might have looked down upon had not experience taught me to look up. (1926, p. 77)

Speech at a dinner held by the Bar Association of Boston, 7 March 1900:

I often imagine Shakespeare or Napoleon summing himself up and thinking: “Yes, I have written five thousand lines of solid gold and a good deal of padding—I, who would have covered the milky way with words which outshone the stars!” “Yes, I beat the Austrians in Italy and elsewhere: I made a few brilliant campaigns, and I ended in middle life in a cul-de-sac—I, who had dreamed of a world monarchy and Asiatic power.” We cannot live our dreams. We are lucky enough if we can give a sample of our best, and if in our hearts we can feel that it has been nobly done. …

The joy of life is to put one’s power in some natural and useful or harmless way. There is no other. and the real misery is not to do this. … This country has expressed in story—I suppose because it has experienced it in life—a deeper abyss, of intellectual asphyxia, or vital ennui, when powers conscious of themselves are denied their chance.

The rule of joy and the law of duty seem to me all one. I confess that altruistic and cynically selfish talk seem to me about equally unreal. With all humility, I think “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might,” infinitely more important than the vain attempt to love one’s neighbor as one’s self. If you want to hit a bird on the wing, you must have all your will in a focus, you must not be thinking about yourself, and equally, you must not be thinking about your neighbor; you must be living in your eye on that bird. Every achievement is a bird on the wing. …

Life is action, the use of one’s powers. As to use them to their height is our joy and duty, so it is the one end that justifies itself. Until lately, the best thing that I was able to think of in favor of civilization, apart from blind acceptance of the order of the universe, was that it made possible the artist, the poet, the philosopher, and the man of science. But I think that is not the greatest thing. Now I believe that the greatest thing is a matter that comes directly home to us all. When it is said that we are too much occupied with the means of living to live, I answer that the chief worth of civilization is just that it makes the means of living more complex; that it calls for great and combined intellectual efforts, instead of simple, uncoördinated ones, in order that the crowd may be fed and clothes and housed and moved from place to place. Because more complex and intense intellectual efforts mean a fuller and richer life. They mean more life. Life is an end in itself, and the only question as to whether it is worth living is whether you have enough of it. … (pp. 77-80)

From a Memorial Day address, 30 May 1884:

The soldiers [during the Civil War] who were doing their best to kill one another felt less of personal hostility, I am very certain, than some who were not imperiled by their mutual endeavors. I have heard more than one of those who had been gallant and distinguished officers of the Confederate side say that they had no such feeling. I know that I and those whom I knew best had not. We believed that it was most desirable that the North should win; we believed in the principle that the Union is indissoluble; we, or many of us at least, also believed that the conflict was inevitable, and that slavery had lasted long enough. But we equally believed that those who stood against us held just as sacred convictions opposite of our, and we respected them as every man with a heart must respect those who give all for their belief. …

[T]o the indifferent inquirer who asks why Memorial Day is still kept up we may answer, It celebrates and solemnly reaffirms from year to year a national act of enthusiasm and faith. It embodies in the most impressive form our belief that to act with enthusiasm and faith is the condition of acting greatly. To fight out a war, you must believe something and want something with all your might. So must you do to carry anything else to an end worth reaching. More than that, you must be willing to commit yourself to a course, perhaps a long and hard one, without being able to foresee exactly where you will come out. All that is required of you is that you should go somewhither as hard as ever you can. The rest belongs to fate. …

I think that, as life is action and passion, it is required of a man that he should share the passion and action of his time at peril of being judged not to have lived. …

Although desire cannot be imparted by argument, it can be by contagion. Feeling begets feeling, and great feeling begets great feeling. … I believe from the bottom of my heart that our memorial halls and statues and tablets, the tattered flags of our regiments gathered in the Statehouses, and this day with its funeral march and decorated graves, are worth more to our young men by way of chastening and inspiration than the monuments of another hundred years of peaceful life could be. …

[T]he generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. Through our great good fortune, in our youth your hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing. … (pp. 80-86)

From a Memorial Day address at a meeting called by the graduating class of Harvard University, 30 May 1895:

[A]lthough the generation born about 1840, and now governing the world, has fought two at least of the greatest wars in history, and has witnessed others, war is out of fashion, and the man who commands the attention of his fellows is the man of wealth. Commerce is the great power. The aspirations of the world are those of commerce. Moralists and philosophers, following its lead, declare that war is wicked, foolish, and soon to disappear.

The society for which many philanthropists, labor reformers, and men of fashion unite in longing is one in which they may be comfortable and may shine without much trouble or any dangers. The unfortunately growing hatred of the poor for the rich seems to me to rest on the belief that money is the main thing (a belief in which the poor have been encouraged by the rich), more than on any grievance. Most of my hearers would rather that their daughters or their sisters should marry a son of one of the great rich families than a regular army officer, were he as beautiful, brave, and gifted as Sir William Napier. I have heard the question asked whether our war was worth fighting, after all. There are many, poor and rich, who think that love of country is an old wife’s tale, to be replaced by interest in a labor union, or, under the name of cosmopolitanism, by a rootless self-seeking search for a place where the most enjoyment may be had at the least cost. …

[A] whole literature of sympathy has sprung into being which points out in story and in verse how hard it is to be wounded in the battle of life, how terrible, how unjust it is that any one should fail. …

For my own part, I believe that the struggle for life is the order of the world, at which it is vain to repine. I can imagine the burden changed in the way in which it is to be borne, but I cannot imagine that it ever will be lifted from men’s backs. …

Behind every scheme to make the world over, lies the question, What kind of a world do you want? The ideals of the past for men have been drawn from war, as those for women have been drawn from motherhood. For all our prophecies, I doubt if we are ready to give up our inheritance. Who is there who would not like to be thought a gentleman? Yet what has that name been built on but the soldier’s choice of honor rather than life? … if we try to claim it [honor] at less cost than a splendid carelessness for life, we are trying to steal the good will without the responsibilities of the place. We will not dispute about tastes. The man of the future may want something different. … I do not know the meaning of the universe. But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has no notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

Most men who know battle know the cynic force with which the thoughts of common sense will assail them in times of stress; but they know that in their greatest moments faith has trampled those thoughts under foot. …

From the beginning, to us, children of the North, life has seemed a place hung about by dark mists, out of which come the pale shine of dragon’s scales, and the cry of fighting men, and the sound of swords. Beowulf, Milton, Dürer, Rembrandt, Schopenhauer, Turner, Tennyson, from the first war-song of our race to the stall-fed poetry of modern English drawing-rooms, all have had the same vision, and all have had a glimpse of a light to be followed. “The end of worldly life awaits us all. Let us who may, gain honor ere death. That is best for a warrior when he is dead.” So spoke Beowulf a thousand years ago. …

War, when you are at it, is horrible and dull. It is only when time has passed that you see that its message was divine. I hope it may be long before we are called again to sit at that master’s feet. But some teacher of the kind we all need. In this snug, over-safe corner of the world we need it, that we may realize that our comfortable routine is no eternal necessity of things, but merely a little space of calm in the midst of the tempestuous untamed streaming of the world, and in order that we may be ready for danger. We need it in this time of individualist negation, with its literature of French and American humor, revolting at discipline, loving flesh-pots, and denying that anything is worthy of reverence—in order that we may remember all that buffoons forget.

We need it everywhere and at all times. For high and dangerous action teaches us to believe as right beyond dispute things for which our doubting minds are slow to find words of proof. Out of heroism grows faith in the worth of heroism. The proof comes later, and even may never come. Therefore I rejoice at every dangerous sport which I see pursued. The students at Heidelberg, with their sword-slashed faces, inspire me with sincere respect. I gaze with delight upon our polo-players. If once in a while in our rough riding a neck is broken, I regard it, not as a waste, but as a price well paid for the breeding of a race fit for headship and command. …

It is the more necessary to learn the lesson afresh from perils newly sought, and perhaps it is not vain for us to tell the new generation what we learned in our day, and what we still believe. That the joy of life is living, is to put out all one’s powers as far as they will go; that the measure of power is obstacles overcome; to ride boldly at what is in front of you, be it fence or enemy; to pray, not for comfort, but for combat; to keep the soldier’s faith against the doubts of civil life, more besetting and harder to overcome than all the misgivings of the battlefield, and to remember that duty is not to be proved in the evil day, but then to be obeyed unquestioning; to love glory more than the temptations of wallowing ease, but to know that one’s final judge and only rival is oneself; with all our failures in act and thought, these things we learned from noble enemies in Virginia or Georgia or on the Mississippi, thirty years ago; these things we know to be true. …

Whatever glory yet remains for us to win must be won in the council or the closet, never again in the field. I do not repine. We have shared the incommunicable experience of war; we have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top. … (pp. 87-93)

Life is painting a picture, not doing a sum. As twenty men of genius looking out of the same window will paint twenty different canvases, each unlike all the others, and every one great, so, one comes to think, men may be pardoned for the defects of their qualities if they have the qualities of their defects. (1911, p. 94)

Man is born a predestined idealist, for he is born to act. To act is to affirm the worth of an end, and to persist in affirming the worth of an end is to make an ideal. The stern experience of our youth helped to accomplish the destiny of fate. It left us feeling through life that pleasures do not make happiness and that the root of joy as of duty is to put out all one’s powers toward some great end. (1911, p. 95)

When one listens from above the roar of a great city, there comes to one’s ears—almost indistinguishable, but there—the sound of church bells, chiming hours, or offering pause in the rush, a moment for withdrawal and prayer. … Life is a roar of bargain and battle, but in the very heart of it there rises a mystic spiritual tone that gives meaning to the whole. It transmutes the dull details into romance. It reminds us that our only but wholly adequate significance is as parts of the unimaginable whole. It suggests that even while we think that we are egotists we are living to ends outside ourselves. (1911, p. 95)

The power of honor to bind men’s lives is not less now than it was in the Middle Ages. Now as then it is the breath of our nostrils; it is that for which we live, for which, if need be, we are willing to die. It is that which makes the man whose gift is the power to gain riches sacrifice health and even life to the pursuit. It is that which makes the scholar feel that he cannot afford to be rich. I know … that there is a motive above even honor which may govern men’s lives. I know that there are some rare spirits who find the inspiration of every moment, the aim of every act, in holiness. (1886, pp. 95-96)

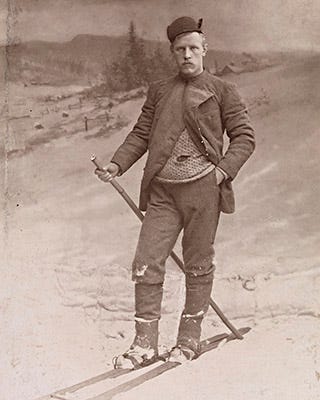

I know of no true measure of men except the total of human energy which they embody—counting everything, with due allowance for quality, from [Fridtjof] Nansen’s power to digest blubber or to resist blubber, up to his courage, or to Wordsworth’s power to express the unutterable, or to Kant’s speculative reach. The final test of this energy is battle in some form—actual war—the crush of Arctic ice—the fight for mastery in the market or the court. … The most powerful men are apt to go into the melee and fall or come out generals. (1897, p. 97)

Nature has but one judgment on wrong conduct—if you can call that a judgment which seemingly has no reference to conduct as such—the judgment of death. That is the judgment or the consequence which follows uneconomical expenditure if carried far enough. If you waste too much food you starve; too much fuel, you freeze; too much nerve tissue, you collapse. And so it might seem that the law of life is the law of the herd; that man should produce food and raiment in order that he might produce yet other food and other raiment to the end of time. Yet who does not rebel at that conclusion? … [E]very joy that gives to life its inspiration consists in an excursion towards death, although wisely stopping short of its goal. Art, philosophy, charity, the search for the north pole, the delirium of every great moment in man’s experience—all alike mean uneconomic expenditure—mean waste—mean a step toward death. … The justification [of art] is in art itself, whatever its economic effect. (1902, p. 98)

The chance of a university to enlarge men’s power of happiness is at least not less than its chance to enlarge their capacity for gain. I own that with regard to this, as with regard to every other aspiration of man, the most important question seems to me to be, what are his inborn qualities?

Mr. Ruskin’s first rule for learning to draw, you will remember, was, Be born with genius. It is the first rule for everything else. If a man is adequate in native force, he probably will be happy in the deepest sense, whatever his fate. But we must not undervalue effort, even if it is the lesser half. (1902, p. 99)

Our tastes are finalities, and it has been recognized since the days of Rome that there is not much use in disputing about them. (1902, p. 99)

I loathe war—which I described when at home with a wound in our Civil War as an organized bore—to the scandal of the young women of the day who thought that Captain Holmes was wanting in patriotism. But I do think that man at present is a predatory animal. I think that the sacredness of human life is a purely municipal ideal of no validity outside the jurisdiction. I believe that force, mitigated so far as may be by good manners, is the ultima ratio, and between two groups that want to make inconsistent kinds of world I see no remedy except force. … [E]very society rests on the death of men. (October 1914, pp. 102-3)

I think the best image for man is an electric light—the spark feels isolated and independent but really is only a moment in a current. (1920, p. 106)

For fifty years it has been my business to know the movement of thought in one of its great expressions—the law—and my pleasure to try to know something of its movement in philosophy, and if anything is plain it is that during the period that counts—from Pericles to now—there has been a gradual advance and that our view of life today is more manifold and more profound than it ever has been before. When [a] man said Europe has given us the steam engine, Asia every religion that ever commanded the reverence of mankind—I answered I bet on the steam engine. For the steam engine means science and science is the root from which comes the flower of our thought. (1919, p. 109)

He surprised me also by seeming bothered over a question of the future life [after death]. … when I said I saw no ground for believing in a future life [he] thought that then we were the victims of a cruel joke. I told him he retained a remnant of theology and thought of himself as a little God over against the universe instead of a cosmic ganglion—that any one was free to say I don’t like it [the universe], but that it was like damning the weather—simply a declaration that one was not adapted to the environment—a criticism of self not of the universe. (1921, p. 113)

[M]orals are imperfect social generalizations expressed in terms of feeling, and that to make the generalization perfect we must wash out the emotion and get a cold head. The retail dealers in thought will do the emotionalizing of whatever happens to be accepted doctrine of the day. Nous autres will permit them that. (1914, p. 114)

Man’s “resistiveness” to experience has struck me much of late years. Man believes what he wants to, and is moved only a little by reason. But reason means facts, and if neglected is likely or liable to knock a hole in his boat, but usually it is not big enough to swamp it and he sticks in an old hat and goes on. (1917, p. 114)

The inevitable is not wicked. If you can improve upon it all right, but it is not necessary to damn the stem because you are the flower. (1921, p. 115)

Truth is the unanimous consent of mankind to a system of propositions. It is an ideal and as such postulates itself as a thing to be attained, but like other good ideals it is unattainable and therefore may be called absurd. Some ideals, like morality, a system of specific conduct for every situation, would be detestable if attained and therefore the postulate must be conditioned—that it is a thing to be striven for on the tacit understanding that it will not be reached… (1920, p. 115)

To Harold Laski, a British socialist economist and politician:

Your remark about the “oughts” and system of values in political science leaves me rather cold. If, as I think, the values are simply generalizations emotionally expressed, the generalizations are matters for the same science as other observations of fact. … Of course different people, and especially different races, differ in their values—but those differences are matters of fact and I have no respect for them except my general respect for what exists. Man is an idealizing animal—and expresses his ideals (values) in the conventions of his time. I have very little respect for the conventions in themselves, but respect and generally try to observe those of my own environment as the transitory expression of an eternal fact… (1926, p. 116)

I often think of the way our side shrieked during the late war [World War I] at various things done by the Germans such as the use of gas. We said gentlemen don’t do such things—to which the Germans: “Who the hell are you. We do them.” There was no superior tribunal to decide. (1930, p. 117)

[To the Neo-Kantian idealist, experience] takes place and is organized in consciousness, by its machinery and according to its laws… Therefore consciousness constructs the universe and as the fundamental fact is entitled to fundamental reverence. From this it is easy to proceed to the Kantian injunction to regard every human being as an end in himself and not as a means.

I confess that I rebel at once. If we want conscripts, we march them up to the front with bayonets in their rear to die for a cause which perhaps they do not believe. The enemy we treat not even as a means but as an obstacle to be abolished, if so it may be. I feel no pangs of conscience over either step, and naturally am slow to accept a theory that seems to be contradicted by practices that I approve. (1915, p. 117)

There is every reason also for trying to make our desires intelligent. The trouble is that our ideals for the most part are inarticulate, and that even if we have made them definite we have very little experimental knowledge of the way to bring them about. … I hold to a few articles of a creed that I do not expect to see popular in my day. I believe that the wholesale social regeneration which so many now seem to expect, if it can be helped by conscious, coordinated human effort, cannot be affected appreciably by tinkering with the institution of property, but only by taking in hand life and trying to build a race. That would be my starting point for an ideal for the law. The notion that with socialized property we should have women free and a piano for everybody seems to me an empty humbug. (1915, p. 118)

Our system of morality is a body of imperfect social generalizations expressed in terms of emotion. To get at its truth, it is useful to omit the emotion and ask ourselves what those generalizations are and how far they are confirmed by fact accurately ascertained. (1915, p. 119)

It is fashionable nowadays to emphasize the criterion of social welfare as against the individualistic eighteenth century bills of rights … The trouble with some of those who hold to that modest platitude is that they are apt to take the general premise as sufficient justification for specific measures. One may accept the premise in good faith and yet disbelieve all the popular conceptions of socialism, or even doubt whether there is a panacea in giving women votes. Personally I like to know what the bill is going to be before I order a luxury. (1915, p. 119)

It has always seemed to us a singular anomaly that believers in the theory of evolution and in the natural development of institutions by successive adaptations to the environment should be found laying down a theory of government intended to establish its limits once for all by a logical deduction from axioms. (1873, p. 121)

The struggle for life, undoubtedly, is constantly putting the interests of men at variance with those of the lower animals. And the struggle does not stop in the ascending scale with the monkeys, but is equally the law of human existence. Outside of legislation this is undeniable. It is mitigated by sympathy, prudence, and all the social and moral qualities. But in the last resort a man rightly prefers his own interest to that of his neighbor. And this is as true in legislation as in any other form of corporate action. All that can be expected from modern improvements is that legislation should easily and quickly, yet not too quickly, modify itself in accordance with the will of the de facto supreme power in the community, and that the spread of an educated sympathy should reduce the sacrifice of minorities to a minimum. But whatever body may possess the supreme power for the moment is certain to have interests inconsistent with others which have competed unsuccessfully. The more powerful interests must be more or less reflected in legislation, which, like every other device of man or beast, must tend in the long run to aid the survival of the fittest. … But it is no sufficient condemnation of legislation that it favors one class at the expense of another; for much or all legislation does that; and nonetheless when the bona fide object is the greatest good of the greatest number. Why should the greatest number be preferred? Why not the greatest good of the most intelligent and most highly developed? The greatest good of a minority in our generation may be the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run. (1873, p. 122)

Of course, as the size of a private fortune increases, the interest of the public in the administration of it increases. … [A] great fortune does not mean a corresponding consumption, but a power of command; that some one must exercise that command, and that I know of no way of finding the fit man so good as the fact of winning it in the competition of the market. …

Taxes … mean an abstraction of a part of the annual product for government purposes, and cannot mean anything else. Whatever form they take in their imposition they must be borne by the consumer, that is, mainly by the working-men and fighting-men of the community. (1904, pp. 128-9)

I always have said that the rights of a given crowd are what they will fight for. (1925, p. 141)

I think the most harmful thing that can be done is done by such of the Rooseveltian manifestos as I have seen. For they touch and irritate the sensitive points of the social consciousness and suggest in a vague and shocking way that something would happen if only they got in; whereas I should like to see the truth told, that legislation can’t cure things, that the crowd now has substantially all there is, that the sooner they make up their mind to it the better, and that the fights against capital are simply fights between the different bands of producers only properly to be settled by the equilibrium of social desires. (1912, p. 141)

[J]ust as … I take no stock of abstract rights, I equally fail to respect the passion for equality. I think it an ignoble aspiration which only culminates in the statement of one of your Frenchmen that inequality of talents was an injustice. (1925, p. 142)

For a quarter of a century I have said that the real foundations of discontent were emotional not economic, and that if the socialists would face the facts and put the case on that ground I should listen to them with respect.” (1912, p. 142)

[C]lass for class I think the one that communism would abolish is more valuable—contributes more, a great deal more, than those whom communism exalts. … [T]he only contribution that any man makes that can’t be got more cheaply from the water and the sky is ideas—the immediate or remote direction of energy which man does not produce, whether it comes from his muscles or a machine. Ideas come from the despised bourgeoisie not from labor. (1927, p. 144)

[O]ur tastes differ. That is the justification of war—if people vehemently want to make different kinds of worlds I don’t see what there is to do except for the most powerful to kill the others—as I suppose they [the Communists] did in Russia. I believe Kropotkin points out the mistake of the French Revolution in not doing so… (1928, pp. 144-5)

But we must take such things [being attacked as representing money-power and plutocratic class interests] philosophically and try to see what we can learn from hatred and distrust and whether behind them there may not be some germ of inarticulate truth. (1913, p. 145)

When the ignorant are taught to doubt they do not know what they safely may believe. And it seems to me that at this time we need education in the obvious more than investigation of the obscure. (1913, p. 145)

Most men think dramatically, not quantitatively, a fact that the rich should be wise to remember more than they do. (1913, p. 146)

We are apt to think of ownership as a terminus, not as a gateway, and not to realize that except the tax levied for personal consumption large ownership means investment, and investment means the direction of labor towards the production of the greatest returns—returns that so far as they are great show by that very fact that they are consumed by the many, not alone by the few. … [T]he function of private ownership is to divine in advance the equilibrium of social desires—which socialism equally would have to divine, but which, under the illusion of self-seeking, is more poignantly and shrewdly foreseen [under capitalism]. …

The hated capitalist is simply the mediator, the prophet, the adjuster according to his divination of future desire. (1913, pp. 146-7)

[L]aw embodies beliefs that have triumphed in the battle of ideas and then translated themselves into action. (1913, pp. 147)

I have no belief in panaceas and almost none in sudden ruin. (1913, pp. 147)

If I feel what are perhaps an old man’s apprehensions, that competition from new races will cut deeper than working men’s disputes and will test whether we can hang together and can fight; if I fear that we are running through the world’s resources at a pace that we cannot keep; I do not lose my hopes. I do not pin my dreams for the future to my country or even to my race. I think it probable that civilization somehow will last as long as I care to look ahead—perhaps with smaller numbers, but perhaps also bred to greatness and splendor by science. I think it not improbable that man, like the grub that prepares a chamber for the winged thing it never has seen but is to be—that man may have cosmic destinies that he does not understand. And so beyond the vision of battling races and an impoverished earth I catch a dreaming glimpse of peace. (1913, pp. 148)

The law is the witness and external deposit of our moral life. Its history is the history of the moral development of the race. (1897, p. 161)

Sovereignty is a question of power, and no human power is unlimited. (1922, p. 234)

Legal obligations that exist but cannot be enforced are ghosts that are seen in the law but that are elusive to the grasp… (1922, p. 234)

The famous opening of Holmes’ 1881 book The Common Law:

The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics. (p. 237)

On the right of Congress to legislate a minimum wage in the District of Columbia:

The end—to remove conditions leading to ill health, immorality, and the deterioration of the race—no one would deny to be within the scope of constitutional legislation. The means are means that have the approval of Congress, of many states, and of those governments from which we have learned our greatest lessons (1923, p. 307)