Repronews #52: Is the Blank Slate doomed?

England gene sequencing 100,000 babies for rare diseases; NYT reports on China pronatalism; Netherlands: richer having more babies; South Korea fertility bump; the case for family-based biobanks

Welcome to the latest issue of Repronews! Highlights from this week’s edition:

Repro/genetics

Genomics England and NHS project to sequence genomes of 100,000 newborns for rare genetic conditions

Population Policies & Trends

The New York Times reports on intrusive pronatal practices in China

Fertility increasingly correlated with income: Higher income men in the Netherlands are over three times more likely to become fathers

South Korea saw continuing fertility bump in August

Genetic Studies

In Nature: the case for family-based sampling for biobanks to better understand genetic effects

Further Learning

Jonathan Anomaly argues new reprogenetic technologies will “break the blank slate” and lead to more public understanding of genetics

Repro/genetics

Britain: “Whole genome sequencing for rare genetic conditions begins in newborns” (PET)

Genomics England, in partnership with Britain’s National Health Service (NHS), is conducting the Generation Study to sequence the genomes of 100,000 newborns.

The study’s principal aim is to evaluate the use of whole genome sequencing

to screen newborns for genetic variants associated with more than 200 treatable rare genetic conditions.

These conditions were selected according to four key principles:

Variants that cause the condition must be able to be reliably detected using genome sequencing.

A high proportion of individuals with those variants should be expected to develop the condition, with a significant impact on quality of life.

An early or pre-symptomatic intervention is available, that could lead to improved outcomes in children.

That intervention must be available and accessible through the NHS.

Conditions covered include:

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID): a disease which without treatment usually leads to infant death within their first year.

Biotinidase deficiency: without treatment, children can have delayed development, seizures and problems with hearing and vision (if diagnosed early, can be treated with a simple biotin vitamin supplement).

The study will ask parents’ permission to securely store their baby’s genome and health data in Genomics England’s National Genomic Research Library. This data will be deidentified and only accessible to approved healthcare researchers.

It is hoped this data will facilitate long-term evaluation of the study to understand the impact of any diagnoses made on families and the health service. In addition, a comprehensive, diverse and longitudinal cohort of genomic and health data will enable wider investigation of questions on the effects of genetics on health.

The study will also investigate the possible risks and benefits of storing an individual’s genome over their lifetime. Upon turning 16, participating children will have the opportunity to decide if they wish to continue or withdraw from the study.

The study has been developed with extensive consultation with the public, parents, and families affected by rare conditions, as well as healthcare professionals, policymakers, and scientists.

The Generation Study is in the early stages, initially being rolled out at 13 NHS hospitals. It will be conducted in around 40 NHS Trusts across England.

People in England can apply to join the study.

More on repro/genetics:

“Dr. Elizabeth Ginsburg sworn in as president of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine” (ASRM)

“Philadelphia-area health systems end use of four race-based algorithms to guide care” (STAT)

“Scientists use CRISPR tools to safely disable gene mutation linked to treatment-resistant melanoma” (Medical Xpress)

Population Policies & Trends

“So, are you pregnant yet? China’s in-your-face push for more babies” (New York Times)

Chinese officials are partnering with universities to develop courses on having “a positive view of marriage and childbearing.”

“I always feel, as a woman, if you’ve done your time on this earth and haven’t given birth to another life, that’s a real pity,” Gao Jie, a delegate from the All-China Women’s Federation, told reporters during a meeting of lawmakers in Beijing this year.

On social media, Chinese women have complained about being approached by neighborhood officials, such as asking about the date of their last menstrual cycle.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping has overseen a crackdown on feminist activism and said promoting childbirth as a national priority is one step toward ensuring that women “always walk with the party.”

China’s total fertility rate is among the world’s lowest at 1.0, compared to 1.62 in the United States last year.

The New York Times visited multiple maternity hospitals and neighborhood officials to investigate efforts to promote fertility. Out of 10 women spoken to, 7 said officials had asked them whether they planned to have children.

Yumi Yang, a 28-year-old married mother, said: “We’re not like people born in the 1970s or ’80s. Everyone knows that people born after the ’90s generally don’t want kids. Whether you want to have children is a very private issue.”

During her pregnancy, government officials repeatedly prompted Yang to take free prenatal vitamins. “When they came to my home, that was really ridiculous,” she said. “I felt a little disgusted.”

“Some people believe that marriage and childbirth are only private matters, and up to each individual. This view is wrong and one-sided,” a government-run family planning association in Mudanjiang, a city of about two million in northern China, said in a news release this year.

Government family planning associations, a network with hundreds of thousands of offshots in villages, workplaces, and urban neighborhoods, are now promoting fertility. These were originally developed to enforce the One-Child Policy.

In Miyun, a district of Beijing with about 500,000 residents, local family planning officials have set up a 500-person propaganda team to promote fertility. The national association boasts that more than half of Miyun’s “suitable-aged” couples had been contacted by the team at least six times. Officials’ bonuses would be pegged to success in promoting the new pronatal culture, although it is unclear how this would be measured.

Many cities offer free premarital health examinations where couples are screened for hereditary diseases and told they should ideally have children before turning 35. Several women said officials called them soon after examination to tell them to collect free folic acid, a prenatal supplement.

Healthcare workers call women during their pregnancies to have check ups. Some women told the Times they appreciated the outreach and felt cared for. Women have also praised parts of the pro-fertility campaign, such as expanding childcare resources and encouraging men to help out at home.

Government pronatal intervention is far less than during the One-Child-Policy era. Professor Wang Feng, a demography expert at the University of California, Irvine, a more interventionist approach would lead to political backlash.

Nonetheless, officials’ overall attitude is similar. “It’s exactly the same mentality as when they implemented birth controls,” Wang said. “The government is, I would say, totally oblivious of how society has moved beyond them.”

The central government has pledged in recent health plans to reduce “medically unnecessary abortions,” setting off social media frenzies from those worried abortion could be restricted. China has one of the highest abortion rates in the world, in part because the One-Child Policy made it so accessible.

In some places, abortion access is overseen by both doctors and officials, a practice original instituted to limit abortion of females.

“Higher incomes now key driver of having kids in the Netherlands” (population.fyi)

New research by Daniël van Wijk of the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute finds that wealthier people in the Netherlands are significantly more likely to become parents.

In 2022, the highest-income quintile of men were 3.11 times more likely to become fathers than the lowest-income quintile, up from 2.38 times in 2008. High-income women were 2.44 times more likely to become mothers in 2022, up from 1.63 times in 2008

The effect strengthened consistently between 2008 and 2022. The effect diminishes for the second child and disappears for the third.

Overall, men in the top income quintile were 1.89 times more likely to have a child than those in the lowest quintile in 2022, up from 1.64 times in 2008. For women, the gap widened from 1.41 times to 1.61 times.

The widening gap is driven by declining fertility among lower-income groups.

The pattern in the Netherlands mirrors trends identified in Norway, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Van Wijk concludes: “Earning a high income constitutes an increasingly strong prerequisite for the transition to parenthood in the Netherlands. This likely contributes to the postponement of parenthood and the decline of fertility and suggests that low-income groups may increasingly be unable to fulfill their fertility desires.”

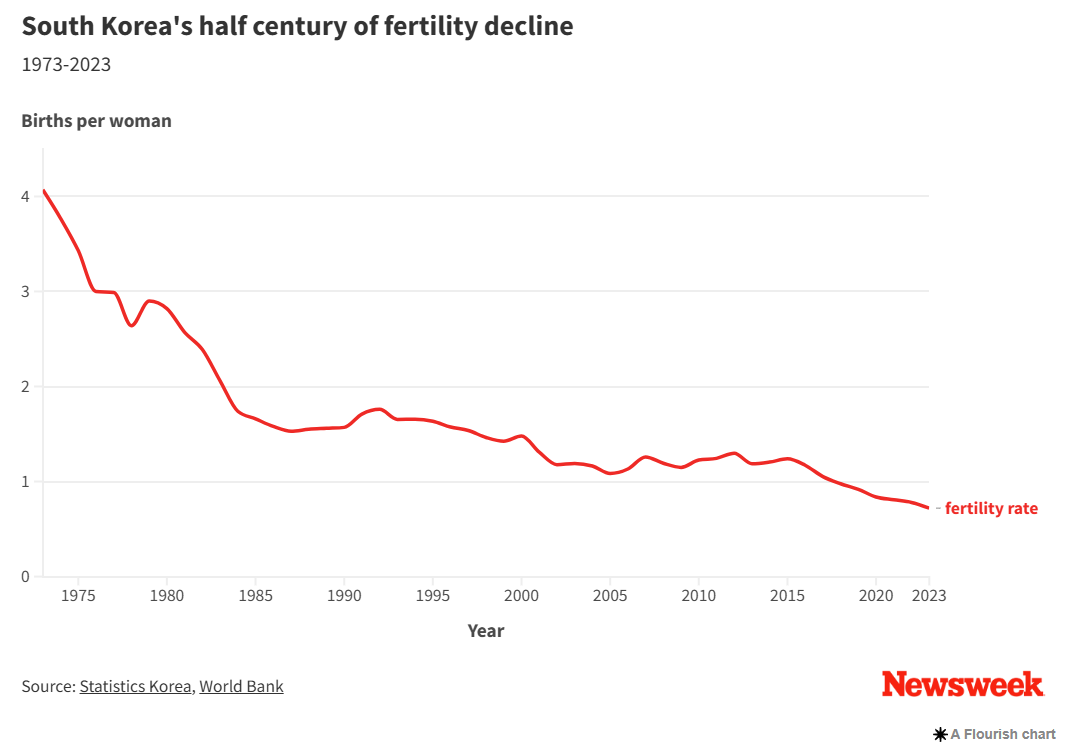

“South Korea’s birth rate sees blimmer of hope” (Newsweek)

South Korea’s statistics agency reports that 20,098 babies were born in August, a 5.9% increase from last year and the second consecutive months of rising births.

The bump may be due to the post-COVD recovery of marriages since 2022.

Last year, the nation’s fertility rate fell to 0.72. President Yoon Suk Yeol has called the declining birth rate a “national emergency” negatively impacting the economy.

Despite over $200 billion in government spending on initiatives such as child care and cash subsidies, these efforts have yet to reverse the trajectory.

More on population policies and trends:

“Are you ready for the baby wars? Global population should probably fall—but the results won’t be pretty” (The Spectator)

Genetic Studies

The importance of family-based sampling for biobanks (Nature)

Neil Davies of University College London and colleagues argue in favor of family-based sampling in biobanks to better undertand genetic factors.

Biobanks have enabled thousands of scientific discoveries across multiple research domains. So far, biobanks have largely had population-based sampling strategies where the individual is unit of sampling, with only sporadic and accidental familial relatedness.

Sampling of close genetic relatives would facilitate research clarifying causal relationships between potential risk factors and outcomes, particularly in estimating of genetic effects.

Further Learning

“Breaking the blank slate: The social consequences of polygenic selection” (Psychology Today)

Jonathan Anomaly, a philosopher and author of Creating Future People: The Science and Ethics of Human Enhancement, notes how genetic explanations for behavior became taboo after the Second World War due to Nazi atrocities.

A survey of sociologists found that only 1/3 believe biology explains why men engage in more violent crime than women.

“While ideology often trumps common sense in the public arena, intellectuals understand the reality of genetic influence when it comes to their private choices,” Anomaly writes. “They are often very selective about the traits of the person they choose to marry and have children with, just as gay couples select sperm and egg donors on the basis of traits they want in their kids. Many people are blank-slatists in the streets, but hereditarians between the sheets.”

Twin and adoption studies and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have shown that psychological differences are significantly the result of genetic differences. This is known as “the first law of behavioral genetics.”

In their highly-cited article “Top 10 Replicated Findings From Behavioral Genetics,” Robert Plomin and colleagues go so far as to say: “Significant and substantial genetic influence on individual differences in psychological traits is so widespread that we are unable to name an exception.”

Anomaly argues resistance to the idea of genetic influence among academics and journalists is rooted in the belief that if genetic influence were widely acknowledged, this would undermine the liberal commitment to moral equality.

Anomaly argues that advances in reprogenetic technologies, especially polygenic embryo selection, will change cultural attitudes: “When couples use IVF to have children, they often have multiple embryos. It will soon be possible to select on the basis of any measurable psychological trait—intelligence, conscientiousness, happiness, criminality, etc. Once polygenic screening for socially significant psychological traits is publicly available, it will bring profound cultural change. This change will not be a direct consequence of the technology, but will instead result from the fact that the option of choosing—or even altering—our genetic predispositions will put a tax on believing the blank slate.”

Increased skin in the game may change attitudes: “When beliefs have no impact on a person’s life, there is little risk in believing things that are untethered to reality. But when parents learn that the genes of their future child could be influenced with technology, they will pay more attention to the influence of genetics on life outcomes.”

The market for polygenic embryo selection will initially be limited by the price of IVF and genotyping embryos. Prices will eventually fall (and many governments may promote access), prompting more parents to consider using the technology.

Anomaly predicts: “Initially many American elites will privately use polygenic screening but publicly condemn it. But a gap will grow between what is privately done and publicly said. At some point, some people will stop lying in public, initially at a cost to themselves. Finally, a preference cascade will lead ordinary people to move from skepticism to endorsement—not only of technologies like embryo selection and gene editing, but of the science of heritability that makes it all possible. Once that happens, the blank slate will crumble and fields like social genomics will replace what we currently call sociology.”

Anomaly concludes: “the love parents have for their children is so strong that they will be driven to learn the truth about genetic influence.”

The best exploration of the intellectual rise of the blank slate is no doubt Steven Pinker’s 2002 book The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature.

More on human nature, evolution, and biotech:

Evolution

“The human race is suffering from success” (Financial Times)

Biotech

Ge Bai, professor of accounting and health at Johns Hopkins Univeristy, “We must win the race for global biotech innovation” (Forbes)

Angela Ailloni, Gingko Bioworks and Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), “Investing in biomanufacturing is key to advancing American innovation” (RealClearHealth)

Environment

European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA): “Scientists from 33 European countries join forces to generate reference genomes for the continent’s biological diversity” (Phys)

“A new startup has joined the effort to genetically upgrade forests. The chestnut tree is first on their list” (GLP/MIT Technology Review)

Agrifood

“Britain’s new Labor government signals it will move forward legislation to open the door to CRISPR and other crop gene editing innovations” (GLP)

Disclaimer: We cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect our own.

Excellent roundup. Many thanks!

BTW, the NYT coverage of Chinese reproduction policies is, as usual, wildly skewed and culturally blind, deaf and dumb. Babies, like most things in China, are everybody's business. It's quite common to see older Chinese mothers take infants from strangers's arms, adjust their clothing, burp the, or whatever, then replace them with a few words of advice.

After living together for 4000 years, they're all relatives anyway.