Repronews #62: Are we getting dimmer?

Selection against cognitive ability in 3 generations of Americans; cloning geniuses; mental and health impact of Neanderthal DNA; IQ & personality predict careers

Welcome to the latest issue of Repronews! Highlights from this week’s edition:

Repro/genetics

Emil Kierkegaard makes the case for cloning of geniuses

Population Policies & Trends

Genetic Studies

A study in Behavior Genetics finds selection against educational attainment, cognitive performance, and mental health for three generations of Americans

Scientific American discusses the many studies finding Neanderthal DNA has varied health and mental impacts

Further Learning

A 2023 study explores the impact of people’s IQ, ability to delay gratification, risk-taking, and the Big Five personality traits on income, job type, and status

Repro/genetics

Should geniuses clone themselves? (Emil Kierkegaard)

Danish social scientist Emil Kierkegaard argues in favor of reproductive cloning of humans of great achievement.

Companies currently exist offering to clone (dead) pets such as dogs, cats, horses, and ferrets.

Studies of identical twins suggest that many psychological traits underpinning “eminence” are highly heritable.

Kierkegaard writes: “Why spend time optimizing embryo selection if we can just take a genome we know is good and make more of them? From a family perspective, it doesn’t work so well, as only one ‘parent’ will be related to the child, but from a human achievement perspective, it makes sense.”

“Reproductive cloning of adult humans would result in time-displaced monozygotic twins. But is genius or eminence really heritable? Sure. We know some of the psychological causes of eminence, intelligence, personality, including drive, work ethic etc., all of which are highly heritable when studied individually. So since eminence is a composite trait of these, this composite must also be heritable.”

Reproductive cloning is banned in many jurisdictions but still legal under federal law in the United States. About half of U.S. states have no applicable laws on cloning.

The non-binding 2005 UN Declaration on Human Cloning calls on all countries to “prohibit all forms of human cloning inasmuch as they are incompatible with human dignity and the protection of human life.”

The European Union’s 2000 Charter of Fundamental Rights “prohibit[s] the reproductive cloning of human beings.”

Kierkegaard argues this is “more of a statement of religious feelings than a real law.”

Animal clones appear to be more likely to suffer from health defects, possibly due to incorrect epigenetic reprogramming of the donor genome, leading to inappropriate patterns of gene expression and developmental anomalies.

This still begs question however: if reproductive cloning were safe, would it be unethical for a person to clone themselves?

More on repro/genetics:

“Fresh embryo transfers linked to higher birth rates in women struggling to conceive with IVF” (Euronews)

“Preimplantation genetic testing: Barriers to access in the UK” (PET)

“Indian court allows family’s request for postmortem sperm retrieval” (PET)

British fertility regulator recommends law review on in vitro gametogenesis (PET)

“Mice with two fathers created using genome edited embryonic stem cells” (PET)

Population Policies & Trends

Metropolitan France’s fertility rate falls to 1.59, the lowest in more than a century (PET)

“The UK’s official population projections are too optimistic” (Boom)

“The five stages of Western fertility”: A data-based exploration of Western European marriage and fertility patterns throughout history (Aporia)

Podcast: Daniel Hess discusses birth rates, exploring the impact of population density and housing, lessons from Israel and Mongolia (Aporia)

Genetic Studies

“Natural selection in modern humans: Three generations of selection against educational attainment in the U.S.” (Steve Stewart-Williams)

A new paper in Behavior Genetics looks at natural selection in three generations of modern Americans.

The graph above shows the strength of selection for a range of traits based on the sample’s polygenic scores (i.e., having multiple genes associated with a trait).

The study notably shows selection against educational attainment and cognitive performance, and selection for depressive symptoms, asthma, earlier age of first birth, and lower self-rated health.

The authors write: “The underlying causes of selection seem to have stayed the same over time, so that the effects of selection have accumulated. In particular, selection against traits associated with education clearly predates the development of the U.S. welfare state.”

Based on the findings, the authors estimate that genotypic IQ is declining by 0.6 points per generation, somewhat less than previous studies. (One Icelandic study found a 0.9 point IQ drop every 30 years).

The authors note that besides cognitive decline, there are similar selection differentials for many health related traits: “The selection differential for self-rated health is greater than those for education and cognitive performance. The most significant, positively selected trait was ADHD, which was also found in the UK (Hugh-Jones and Abdellaoui 2022).”

The authors conclude: “Future research should study the health and medical implications of natural selection, in addition to its social implications. To know more, we must await more accurate polygenic scores.”

“How Neanderthal DNA may affect the way we think” (SciAm)

Around 1-2% of DNA in Europeans and Asians stems from Neanderthals.

New studies are regularly emerging on the impact of Neandertal DNA on modern human health and physiology.

Neanderthal genetic variants have been associated with:

More vulnerability to immune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn’s disease.

Modification of the immune molecule interleukin-18, which plays a role in predisposition to autoimmune disorders.

Increased risk for severe COVID.

Development of allergies, including possibly asthma.

Major depression and chronotype (whether someone is a morning or night person).

Substance use such as drinking and smoking.

Pain sensitivity.

ADHD.

Other impacts may include skin and hair color, blood clotting, heart disease, how cells respond to various environmental stressors such as radiation, and proneness to certain skin cancers, thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, obesity and diabetes.

Neanderthal DNA may also influence our brains, despite the fact that it tends to be underrepresented in brain-related genes in modern humans (such regions of the genome are known as “Neanderthal DNA deserts”).

Neanderthal DNA has effects throughout the brain and associated structures. Philipp Gunz of the Max Planck Institute and his colleagues found that people with higher percentages of Neandertal DNA are more likely to have skull shapes that are modestly elongated and reminiscent of the Neandertal skull, particularly around the parietal and occipital regions toward the back of the cranium.

Neandertal variants that are located near the genes UBR4 and PHLPP1 are involved in neuron production and the formation of myelin, the fatty sheath that insulates the axons of larger neurons, allowing them to communicate more reliably over longer distances.

Michael D. Gregory of the National Institutes of Health and his colleagues observed differences in brain structure in regions related to visual processing and socialization. People with more Neandertal DNA tend to have increased connectivity in visual-processing tracts, but reduced connectivity in nearby tracts that are implicated in social cognition. This suggests there could be trade-offs between visual processing and social skills in the Homo lineage.

Neandertal DNA also seems to influence the structure and function of the cerebellum, a region dedicated to motor memory, coordination, attention, emotional regulation, sensory processing and social cognition. The cerebellum seems to be vital for systems involved in mentalizing, which underlies many aspects of our ability to infer the mental states of other people.

In 2018, Takanori Kochiyama of the Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International in Kyoto and his colleagues compared reconstructed crania of Neandertals and those of early modern humans and compared them. The cerebellum was significantly smaller in our extinct cousins. This suggests there could be significant variability in the structure and function of the cerebellum (and therefore in social cognition) in modern humans with Neanderthal DNA.

Paleogenomic research shows Neanderthals experienced a genetic bottleneck between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago, the population dwindling to perhaps as few as 5,000 individuals. As smaller populations find it harder to shed harmful mutations, the Neandertal genome contains many of them. This may be why Neanderthal DNA is often associated with negative traits today.

More on genetic studies:

300 genomic reasons associated with increased risk of bipolar disorder identified (PET)

“Y chromosome genes influencing sperm development identified” (PET)

Further Learning

“How intelligence and personality shape our career trajectories” (Steve Stewart-Williams)

A 2023 study by Tobias Wolfram explores the connections between cognitive ability, personality, and occupational sorting.

Whereas earlier research relied on small or unrepresentative samples, this study draws on data from a representative British sample of more than 40,000 people.

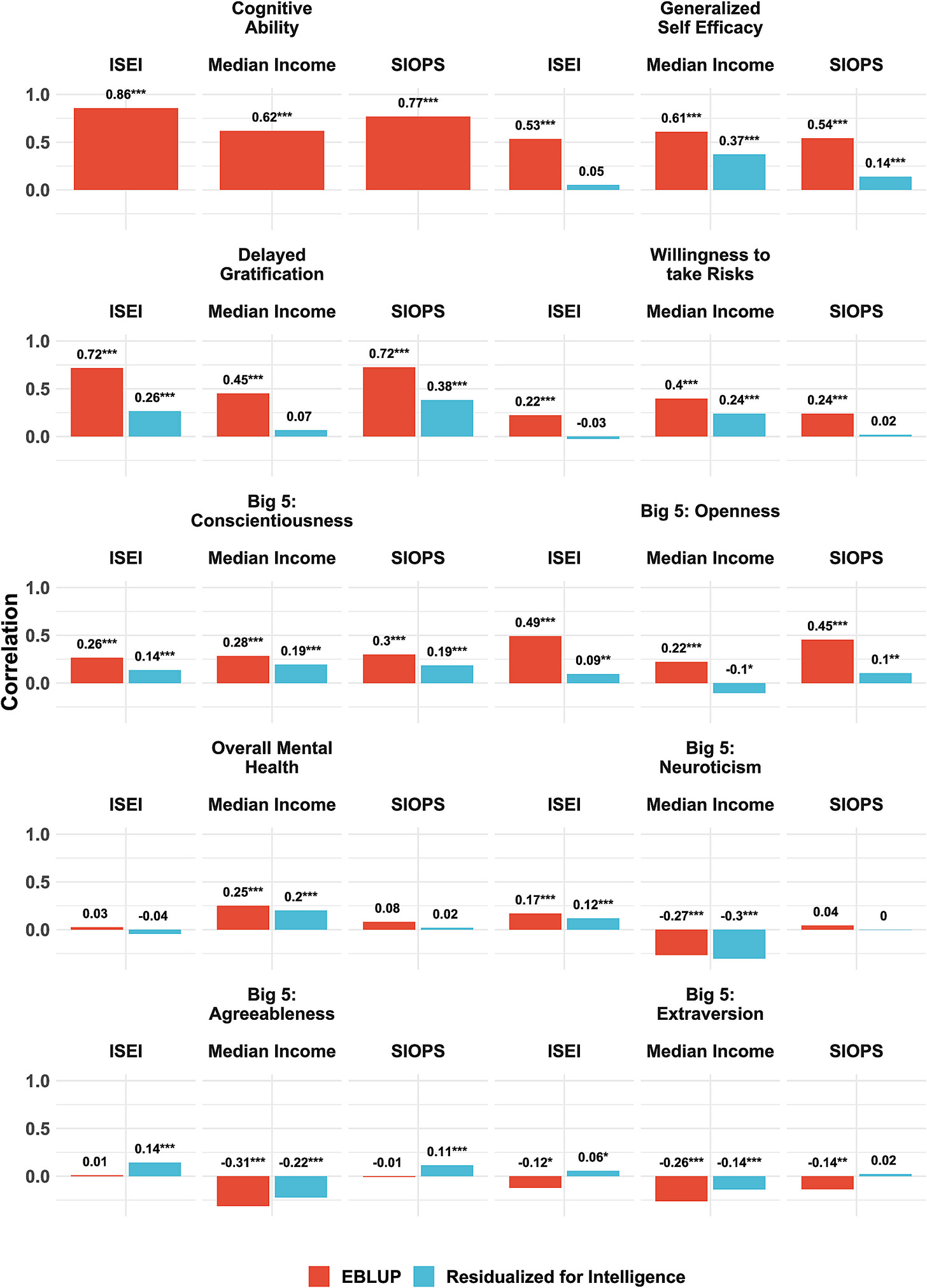

The study confirms the long-standing hypothesis that intelligence plays a pivotal role in determining which careers people end up in, and the status and pay of those careers. It also tracks association with the Big Five personality traits, delayed gratification, self-efficacy, risk-proneness, and mental health.

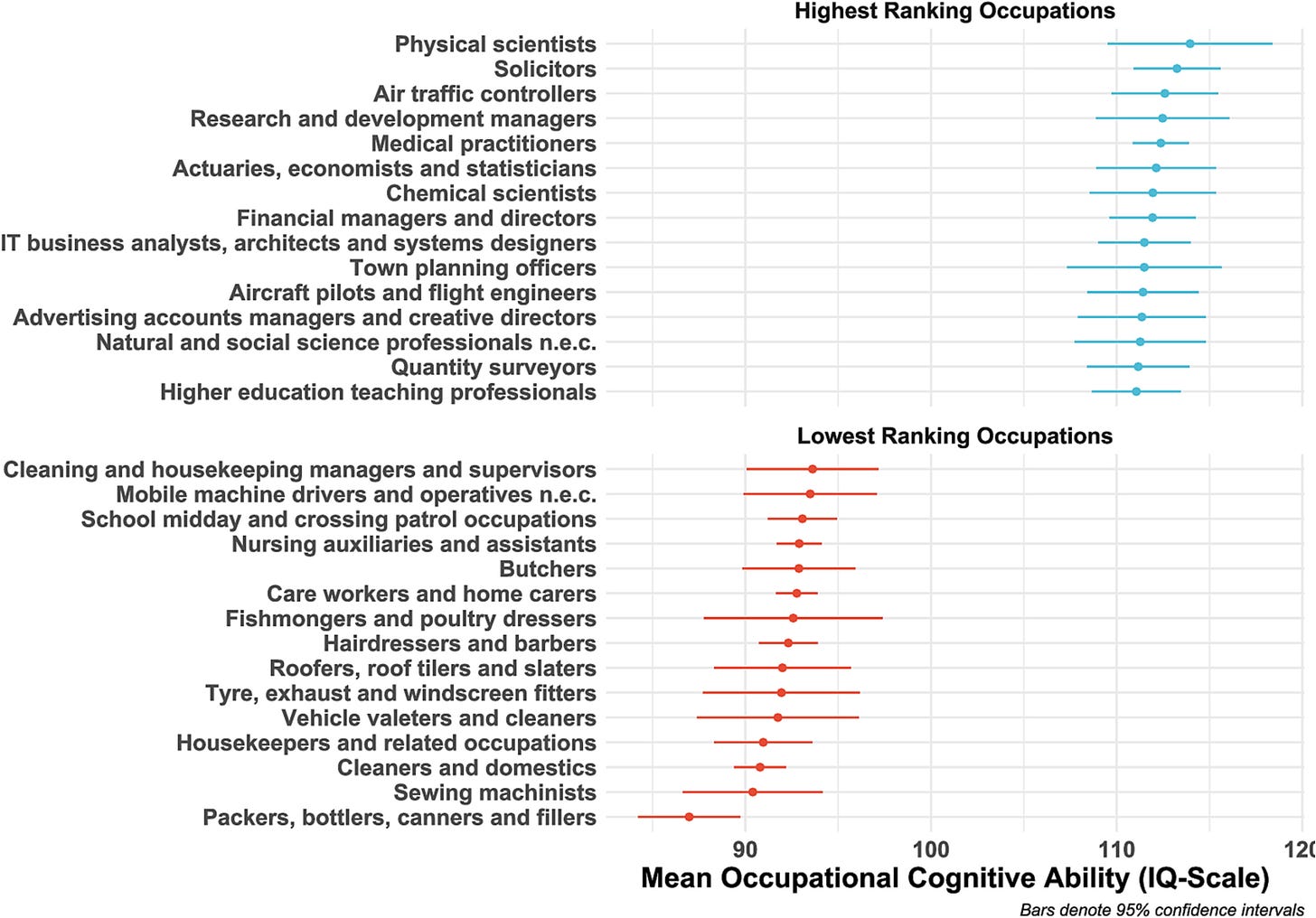

The study also looks at average IQ by profession.

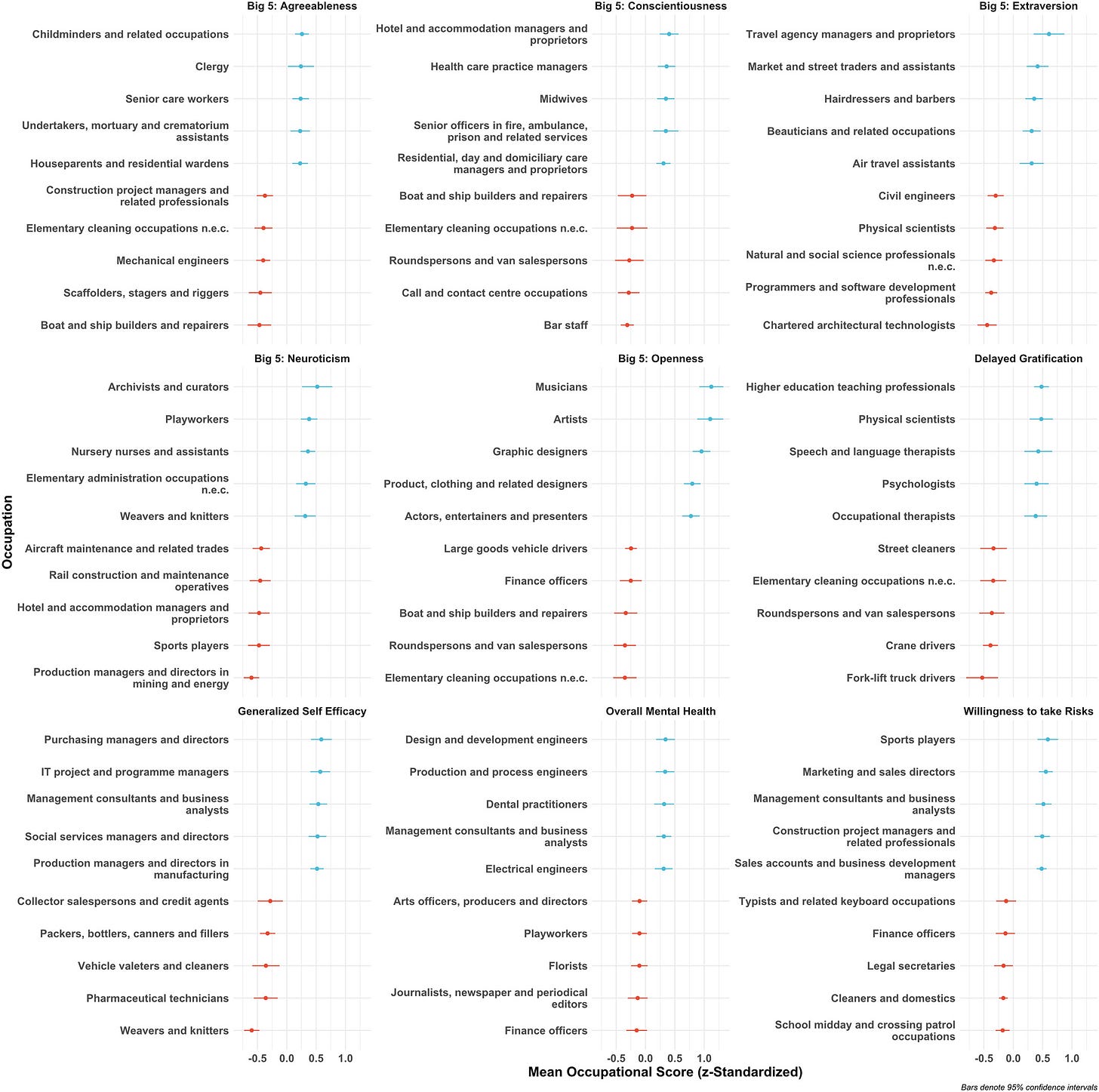

As well as personality traits and profession.

The study also finds that IQ and personality predict job status and income.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the higher a field’s average IQ, the less IQ variation there is in that field.

More on human nature, evolution, and biotech:

“When did north-west Europeans become WEIRD?” (Emil Kierkegaard)

“Neandertal DNA in some of the oldest modern human genomes establishes a short timeline of 50,000 years for the out-of-Africa founder event” (John Hawks)

Disclaimer: We cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect our own.