Repronews #64: Patient perspectives on embryo screening for polygenic diseases

Indian castes’ endogamy & genetic diseases; say hello to “woolly mice”; Africa CDC calls for “Africa-centric” research ethics; a Confucian approach to global bioethics

Welcome to the latest issue of Repronews! Highlights from this week’s edition:

Repro/genetics

Orchid study on patient perspectives on polygenic embryo screening: couples seeking fertility care mostly happy to receive simulated polygenic risk scores for Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, cancers, diabetes, and other common diseases

Population Policies & Trends

Genetic Studies

Indian study explores subcontinent’s genetic architecture, high level of endogamy within castes, and associated diseases

Further Learning

Colossal Biosciences has bred genetically engineered “woolly mice”

Africa CDC to develop an “Africa-centric health research ethics framework” more respectful of African interests and communitarian values

Nancy Jecker and Roger Yat-nork Chung make the case for “a Confucian-inspired approach to global bioethics” based on dialogue, manners (li), and respect for non-individualistic non-Western value systems

Repro/genetics

“Patient perspectives after receiving simulated preconception polygenic risk scores (PRS) for family planning” (JARG)

Researchers at Orchid—a company providing whole genome sequencing of human embryos—and Stanford University explored patient perspectives on the use of Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Polygenic disease (PGT-P) to select embryos with lower risks for common polygenic diseases.

90 participants were recruited from couples seeking OB/GYN or reproductive endocrinology/fertility care from Stanford clinics.

Participants received polygenic risk scores (PRS) for 11 diseases for simulated embryos (estimating increased or decreased risk of developing each disease), were given genetic counseling, and were asked about their perspectives.

The 11 diseases covered were atrial fibrillation, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, bipolar disorder, breast cancer, class III obesity, coronary artery disease, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), prostate cancer, schizophrenia, type 1 diabetes, and type 2 diabetes.

Overall, participants were more supportive of screening embryos for childhood-onset diseases (80%) compared to adult-onset conditions (63%). However, among specific diseases, participants expressed the greatest interest in screening for adult-onset cognitive disorders (schizophrenia, 86%, Alzheimer’s disease, 82%).

Participants’ free responses noted the importance of personalized counseling. Participants of non-European ancestry expressed frustration with PRSs’ limited applicability to them. Negative reactions to testing included nervousness or anxiety (5%) and regret (2%).

The authors note that positive patient interest in polygenic embryo screening is consistent with other U.S. studies. However, as prior studies also show significant clinician unease with this procedure, the results “highlight the need for comprehensive genetic counseling and inclusive stakeholder input in shaping guidelines for PRS during IVF.”

More on repro/genetics:

Dominic Wilkinson, “Banning first cousin marriage would be eugenic and ineffective” (The Conversation)

“IVF patients say a test caused them to discard embryos, now they’re suing” (TIME)

Population Policies & Trends

Podcast: “Unpacking fertility collapse: Causes, consequences, copes, and possible fixes with Robin Hanson” (Conceivable with Noor)

“Nestlé says parents with fewer children buy more expensive baby food” (Financial Times)

Genetic Studies

“Endogamy—a major cause for health disparity in India” (The Hindu)

Indian researchers at the Tata Institute for Genetics and Society and other organizations have conducted a study exploring India’s unique genetic architecture and the implications for human health.

The study suggests the persistent practice of endogamy—marrying within small communities—is a primary cause for population-specific diseases in India.

281 high-coverage whole exome sequences were analyzed from four distinct caste/regional populations.

“We examined several key factors, such as extent of inbreeding and novel genetic variants in populations,” said lead author Pratheusa Maccha. “We also looked at pharmacogenomic markers that influence drug metabolism to understand why different drugs seem to work differently in different populations.”

Study lead Kumarasamy Thangaraj said the study forecasts the impact of endogamy in causing population-specific genetic diseases and drug responses: “This emphasizes the need for appropriate genetic screening, counselling and clinical care for the communities that are vulnerable to various health conditions.”

The Reddy community, a Hindu caste found mainly in South India, was found to have a high prevalence of a gene increasing risk of developing ankylosing spondylitis, a type of arthritis.

The study found that the Yadav, originally from northern India, genetically clustered most with ancestral north Indian populations. This shows the Yadav have been highly endogamous after migrating to southern India (Pondicherry).

Novel genetic variants associated with drug metabolism were identified, affecting reactions to common drugs, such as Tacrolimus (an immunosuppressive drug) and Warfarin (an anticoagulant drug).

“We observed genetic variations in the genes that alters the drug response, which differ across populations, and hence provide opportunity for developing targeted drug and improving health outcomes”, said co-author Divya Tej Sowpati.

The degree of inbreeding (the coefficient) was found be 59% on average across the whole population (by comparison, siblings of unrelated parents have a 25% inbreeding coefficient). A higher coefficient makes it more likely an individual has two pairs of harmful recessive genes.

The inbreeding coefficient varied from 38.4% for the Yadav, 56% for the Reddy, 56.1% for the Kalinga, and 87.5% for the Kallar.

Population-specific harmful genetic variants were found for muscular dystrophies, gastropathy (IBD), diabetes, neuropathies, tarsal tunnel syndrome, deafness, epilepsy, and many other diseases.

The authors write: “India is a land of extraordinary human diversity in terms of cultural, social, and religious practices, with over four thousand anthropologically well-defined population groups, who speak more than 300 different languages. Majority of Indian populations practice strict endogamy, resulting in substantial barriers to gene flow. Consanguinity, i.e., union between close relatives is highly pervasive in Southern India.”

“The rich genetic diversity within these largely endogamous populations, underscores the need to increase the Indian ethnic representation in genetic data, crucial for advancing global precision medicine. Unfortunately, there exists a significant disparity in the inclusion of the non-European population in genomic studies. Capturing the genetic diversity of these underrepresented communities can address the existing disparities and enhance disease risk predictions, early detection, diagnosis, clinical care, and precision medicine.”

“Founder events and population bottlenecks also shape the genetic constitution of Indian populations. Founder events occur when a new population is established by a small group of individuals separating from the ancestral population. This leads to reduced genetic diversity and distinctive allele frequency patterns, often resulting in a higher prevalence of rare recessive diseases. Due to founder events, deleterious variations persist, more so when compounded by inbreeding practices. Such populations are valuable for examining how evolutionary processes influence disease genetics and evolution.”

“Founder events and population bottlenecks significantly reduce genetic diversity and disease risk, with notable genetic findings in populations like the Ashkenazi [Jews], Finnish, Amish, and Icelanders. … In our previous study (Nakatsuka et al., 2017), 81 out of 263 South Asian populations showed stronger founder effects than Finnish and Ashkenazi populations.”

More on genetic studies:

“Genetic vulnerability, air pollution may raise risk of COVID infection, severe outcomes” (CIDRAP)

“Labradors and humans share the same obesity genes—new study” (The Conversation)

Further Learning

“Hoping to revive mammoths, scientists create ‘woolly mice’” (NPR)

Researchers at Colossal Biosciences have genetically engineered mice with some characteristics of the woolly mammoth.

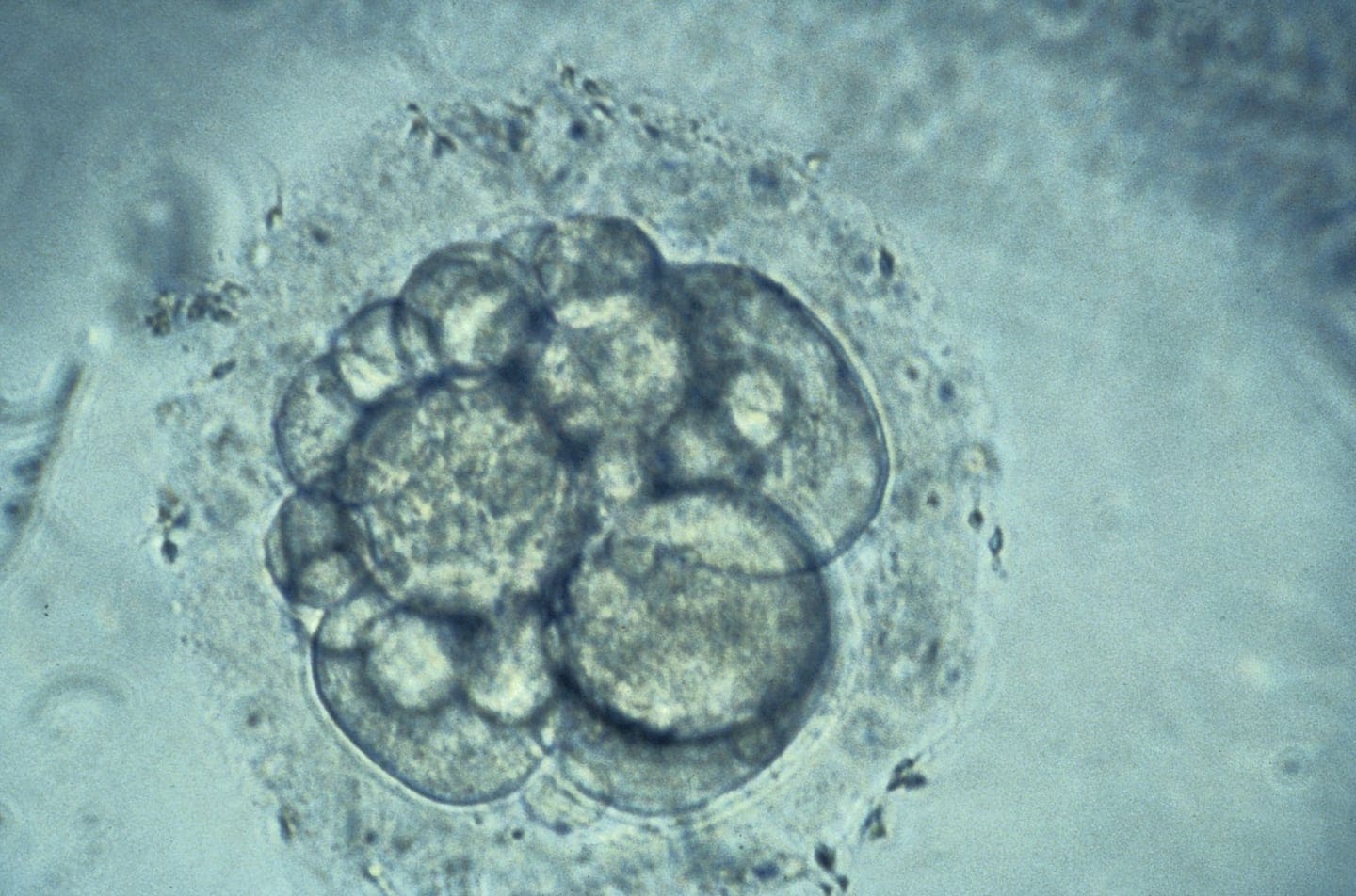

The scientists implanted genetically modified embryos in female lab mice that gave birth to the first of the woolly pups.

“This is really validation that what we have in mind for our longer-term de-extinction project is really going to work,” said Colossal Chief Science Officer Beth Shapiro. The company says reviving extinct species like the mammoth, the dodo, and others could contribute to repairing ecosystems.

The researchers identified genes making mammoths distinctive, comparing ancient samples with genetic sequences of African and Asian elephants. These include genes for long woolly hair and a way of metabolizing fat helping them survive in the cold.

Then, the scientists looked for the same genes in mice and made modifications to produce similar traits. “This is exciting to us because it confirms that the genes and gene families that we identified using our comparative genomics approach really do cause an animal to have a woolly coat” and modified metabolism, said Shapiro. “And this is the way that we’re going to create mammoths for the future.”

Embryos of Asian elephants would be edited for mammoth traits and implanted into female elephants. “Our intention is to re-create these extinct species that played really important roles in ecosystems that are missing because they’ve become extinct,” Shapiro said.

Some scientists argue Colossal is overstating its achievements with the woolly mice. “It’s far away from making a mammoth or a ‘mammoth mouse’,” said Stephan Riesenberg, a genome engineer at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “It’s just a mouse that has some special genes.”

“A call for an Africa-centric health research ethics framework: A way forward for shaping global health research” (The Lancet)

Jean Kaseya, Director General of the Africa Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (Africa CDC), and other agency officials call for an “Africa-centric” health research ethics framework.

Such a framework should reflect Africa’s unique values, protect African research participants’ interests, ensure balanced donor-recipient relations in foreign-funded research projects, and “decolonize public health and research.”

Health research from Africa is scarce despite the continent representing 18% of the world population and 25% of global disease burden. The Africa CDC blames this partly on the lack of an African research ethics framework being ready to swiftly enable timely research against outbreaks in the continent.

The authors write: “African populations have unique cultures, values, belief systems, and virtues that need to be explored and understood to conduct ethical research. … In African settings, unlike high-income countries, more emphasis is placed on community-level autonomy rather than individual autonomy.”

They argue that African populations’ low level of health literacy and lower socioeconomic status can compromise individuals’ ability to provide informed consent and make them vulnerable to exploitation.

Foreign researchers in Africa have sometimes been perceived by local communities as “vampires” who steal and sell blood.

The Africa CDC has proposed developing such a continent-wide Africa-centric research ethics framework in consultation with heads of national ethics committees of African Union countries.

This framework should reflect “the context-specific realities, nuances, and challenges experienced by African countries and participating communities during research in the past and redress these through applying African values and virtues, as well as acceptable ways of conducting research in Africa.”

In addition to existing international research ethics principles, the Africa-centric research ethics framework would consider “key attributes such as solidarity (altruism, reciprocity, and collective responsibility), friendliness (interdependence, interconnection, and respect), and social justice (equitable allocation, moral responsibility, holism, hospitality, and acceptability).”

The framework would consider the rights of communities and regions to make informed decisions about what research to permit, while limiting arbitrariness in health research by setting minimum standards grounded in commonly accepted values across African societies. The framework aims be relevant in the long-term and to enable secondary use of health data for research and policymaking.

The framework would accelerate the establishment of a Continental Health Research Ethics Committee (CH-REC), under the administrative leadership of Africa CDC. Once research is approved by the CH-REC, national research ethics committees would be able to quickly approve country-level research.

The authors conclude: “the Africa-centric health research ethics framework will be instrumental in shaping the global health research efforts on the continent.”

Lessons from li: A Confucian-inspired approach to global bioethics (JoME)

Nancy Jecker and Roger Yat-nork Chung of the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Centre for Bioethics argue for a Confucian-inspired approach to global bioethics as an alternative to the hegemony of individualist Western bioethics.

Jecker and Chung argue mainline bioethics reflects the individualist values of WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic) countries, which are not necessarily shared by Eastern countries: “WEIRDness violates epistemic justice by assigning excess credibility to the West while deflating

the credibility of the East.”

The authors argue that whereas Western liberal ethics tends to see personhood in intrinsic individual terms, Confucian ethics tends to see personhood as reflecting virtuous effort and social relationships.

The authors argue for a “pluriversal” global bioethics that recognizes the legitimacy of different cultures’ moral frameworks and the application of the Confucian virtue of li (ritual propriety and decorum) in intercultural debates.

Li morally prescribes polite behavior “in everyday conduct and interactions with parents, teachers, friends, neighbours, etc., where norms for proper behaviour apply,” not limiting morality to the “big moments” of major decisions sometimes seen in Western ethics.

Applying li would mean“greater tolerance, respect, epistemic justice, cultural humility, and civility” in intercultural debates on global bioethics.

Disclaimer: We cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect our own.