Repronews #71: Lifespan: ~50% genetic?

Screening out blindness | IVF for population growth | chemical damage to gene pool | musical enjoyment ~54% heritable | breast cancer risk of different populations | New Yorker on human biodiversity

Welcome to the latest issue of Repronews! Highlights from this week’s edition:

Repro/genetics

The BBC reports on why content creator Lucy Edwards wants to use IVF to screen out the gene that made her blind

PET hosts a second event on how publicly-funded IVF and other policies can boost population growth

An ethical framework to protect the human gene pool from damage due to chemical pollutants

Genetic Studies

Twin study from Danish and Swedish data finds heritability of lifespan is over 50%, higher than previous estimates

Swedish twin study finds enjoyment of music is about 54% heritable and this is mostly unrelated to genes associated with broader reward sensitivity and musical skills

A genome-wide association study finds genes predisposing for breast-cancer risk in South African black women significantly differ from those in Europeans and West Africans

Further Learning

The New Yorker discusses the importance of recognizing “human biological diversity” in child growth and medicine

Repro/genetics

Why Lucy Edwards wants an IVF baby to screen out gene that made her go blind (BBC)

Lucy Edwards, a blind content creator, TikTok star, and ambassador for the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), is starting IVF treatment but faced a dilemma about screening out the gene that made her blind.

The genetic disorder in question (Incontinentia Pigmenti or IP) runs in Lucy’s female family line and causes blindness, with potential severe outcomes for male pregnancies.

To avoid passing on the gene, Lucy and her partner Ollie have chosen pre-implantation genetic testing (PGT) as part of IVF to select embryos without the genetic condition.

Lucy acknowledges that IVF will “edit out” the gene that defines her life and identity. She and Ollie want to avoid the potential suffering and trauma associated with the gene.

Lucy is excited about the prospect of becoming a mother, although she remains mindful of the ethical implications of her decision. Most people interacting on social media have been supportive.

“What can state-funded IVF do for population growth?” (PET)

British fertility group PET held another event on the role of government-funded fertility treatment in addressing population decline.

Ann Berrington, professor of demography and social statistics at the University of Southampton and director of the Fertility and Family research group, outlined some of the determinants affecting fertility behaviours.

These include “remote” factors such as reduced child mortality, perceived economic uncertainty, and attitudes to gender roles, and “proximate” factors, such as infertility, relationship status, and use of contraception.

She said the impact of cash incentives for children is generally small compared to cultural factors.

Supportive family policies, as found in the Nordic countries, are necessary but not sufficient, as birthrates are still declining in these countries.

Professor Berrington suggested:

Increasing gender equity in terms of sharing childcare and domestic labor more evenly between partners

Improving the availability of affordable housing

Reducing economic barriers (a Finnish study showed that childlessness is growing fastest among those with the least education)

Addressing “subjective economic insecurity”

Enhancing access to assisted conception, making it more affordable and more accessible to diverse types of families

David Bell, emeritus professor of economics at the University of Stirling, noted that Scotland has a low total fertiltiy rate of 1.3 despite having the most generous NHS-funded IVF policy in Britain.

He argues housing costs, the cost of childcare, career pressure, financial insecurity, student debt, individualism, reduced stigma around being childfree, desire for work/life balance, and climate fears may be undermining fertility.

Bell called for a comprehensive approach to fertility decline, respecting individual choice and balancing that with societal needs.

Søren Ziebe, professor of clinical embryology at the University of Copenhagen's Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, defined fertility awareness as “the understanding of reproduction, fecundity and related risk factors, including the awareness of societal and cultural factors affecting options to meet reproductive family-planning and family-building needs.”

Ziebe argued that need for fertility treatment could be reduced by fertility awareness and education. In Denmark, around 12% of women do not become mothers. Many are “childless by circumstance” and would like to have children. He said 11% of children born in Denmark are conceived at a fertility clinic and this may rise further with increased government funding.

Zeibe said even if Denmark’s generous funding were extended across Europe, it is unlikely that it could compensate for projected population decline. Fertility treatment can only be a part of the solution to population decline.

Satu Rautakallio-Hokkanen, director-general of Fertility Europe and contributor to the Economist Impact report Fertility Policy and Practice: A Toolkit for Europe, shared patient perspectives on fertility treatment and population growth.

Around 20% of people of reproductive age face infertility for medical and/or social reasons, such as lack of a partner, one’s economic situation, or state restrictions (such as lack of access to donor gametes for same-sex couples).

Most Finns want a family size of 2 children and only 13% of adults want to remain child-free. However, by age 45, 30% of men and 20% of women are childless. There is a gap between the families people want and what they are having.

To support fertility, a 2024 report from Finland’s Ministry of Social Affairs and Health suggested fertility awareness in schools, reproductive health counselling and services, investing in fertility treatments and prevention of mental health problems, and supporting family-friendly workplaces and work/life balance.

Professor Roger Gosden, a visiting scholar at William and Mary (Virginia), discussed “the Infertility Trap” whereby population decline from low birthrates becomes harder to reverse (a concept developed by John Aitken).

Gosden faulted Elon Musk, who has strongly expressed support for pronatalism, for cutting U.S. federal funding for fertility research. This includes cutting funding for clinical trials in humans for the drug called Rapamycin, which may protect egg quality in later life an d thus prolong fertility.

He noted that use of ICSI, a treatment for male infertility, may be passing on genetic mutations affecting sperm quality, leading male descendants to also require ICSI to conceive.

“Genetic engineering, chemical exposure, and the germline: An ethical synthesis” (Hastings Center)

Anne Le Goff and Hannah Landecker argue that widespread concerns about intentional modification of the heritable human genome should also inform accidental heritable modifications due to pollutants such as chemicals.

They write: “whether the impact of human technological activity on enduring shifts in human heredity occurs via purposeful genetic modification or nondirected changes that undermine genome stability, the result is irreversible genetic change in future generations. This article argues that the robust ethical reflection developed by the bioethics community to address human heritable genome editing can be used as a resource to address understudied questions of moral responsibility for anthropogenic insults to the germline.”

The authors outline a “future-oriented ethical framework” for germline responsibility in a time of concern about industrial chemicals.

More on repro/genetics:

“First baby born following womb transplant in UK” (PET)

“Polygenic scores could ‘turn the tide on prostate cancer’” (PET)

Podcast: Genetics II: Discusses genes’ influence on personality, environmental factors, and recent science (ASRM)

Genetic Studies

“Heritability of human lifespan is about 50% when confounding factors are addressed” (bioRxiv)

Ben Shenhar and coauthors at the Weizmann Institute of Science (Israel), the Karolinska Institute (Sweden), Westlake University (China), and Leiden University (Netherlands) estimate the impact of genes upon lifespan.

Twin studies have typically suggested genes explain 20-25% of lifespan variation, but the authors argue these do not exclude extrinsic mortality (death caused by factors outside the organism’s control).

Using historical twin datasets from Sweden, Denmark, and the Swedish Adoption/Twin Study of Aging (SATSA) study, the authors argue extrinsic mortality drives down measured lifespan correlations among twin pairs.

In the SATSA cohort, heritability climbs across birth cohorts as extrinsic mortality falls.

Excluding extrinsic deaths and analysing survival from age 15 leads to an estimated heritability of lifespan of 54%, similar to most complex traits.

The authors “challenge the consensus that genetics has only a minor effect on lifespan, showing that genetic variation explains about half of human lifespan differences. Our results support renewed efforts to uncover the molecular and genetic mechanisms of aging and translate them into clinical benefits.”

“Scientists find genetic basis for how much people enjoy music” (PsyPost)

Giacomo Bignardi and coauthors at the Max Planck Institute (Netherlands), the Karolinska Institute, Barcelona University, and McGill University, have published a twin study in Nature Communications estimating how much people’s enjoyment of music is influenced by genetic factors.

The researchers found that over half the variation in people’s sensitivity to musical pleasure is related to genetic differences.

These genetic influences seems mostly unrelated to broader reward sensitivity or basic musical skills like pitch or rhythm perception.

The findings suggest music enjoyment is not simply a byproduct of general brain function, but may instead have distinct biological roots.

Music is a universal human behavior playing an important role in emotion, culture, and social bonding, but its origins remain elusive.

The researchers used data from the Swedish Twin Registry, a large database including thousands of adult twins, to analyze responses from over 9000 individuals who had completed the Barcelona Music Reward Questionnaire (BMRQ), a survey measuring how much pleasure people experience from music.

The questionnaire assesses five areas: emotional reactions to music, using music to regulate mood, seeking out new music, enjoying movement related to music (like dancing), and the pleasure of social bonding through music.

The researchers also gathered data on participants’ basic music perception abilities (such as pitch and rhythm discrimination) and their general sensitivity to rewarding experiences.

The researchers found that identical twins were significantly more similar in how much they enjoyed music compared to fraternal twins.

The researchers estimated that about 54% of the variation in music enjoyment could be attributed to genetic factors.

After accounting for genes related to basic music skills or general pleasure-seeking behavior, nearly 40% of the variation in music enjoyment could be traced to genetic factors unique to music enjoyment itself.

The genetic contributions to music enjoyment were not uniform. Each of the five aspects of musical enjoyment—emotional response, mood regulation, music seeking, sensory-motor pleasure, and social bonding—had only partly overlapping genetic influences.

For example, the researchers found that the pleasure people get from the social aspects of music (e.g., bonding at concerts or group singing) was more strongly related to genes involved in basic music perception than other facets were. This could reflect the social bonding function of music in human evolution.

The study did not find evidence for a single overarching genetic factor influencing all facets of music enjoyment equally. Each facet had its own combination of genetic influences, suggesting that the ability to enjoy music is built from several distinct components. Musicality may not be a single trait, but a complex set of abilities and experiences.

“These findings suggest a complex picture in which partly distinct DNA differences contribute to different aspects of music enjoyment,” said Bignardi. “Future research looking at which part of the genome contributes the most to the human ability to enjoy music has the potential to shed light on the human faculty that baffled Darwin the most, and which still baffles us today.”

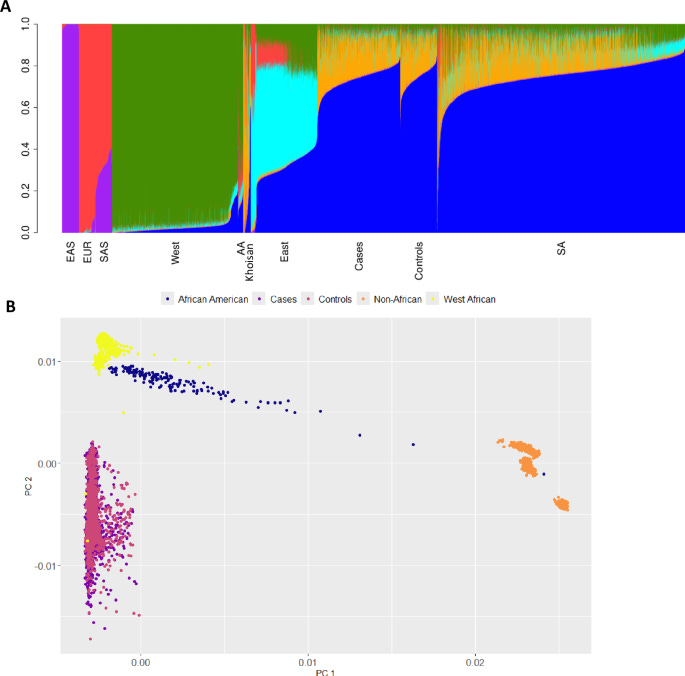

“GWAS identifies common variants associated with breast cancer in South African black women” (Nature Communications)

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have characterized the contribution of common genetic variants to breast cancer-risk in people of European ancestry.

This GWAS explored the genetic contribution to breask-cancer risk in black South Africans, with data from 2485 women with breast cancer and 1101 controls.

Two novel risk loci were identified. These did not replicate in breast cancer GWAS data from populations of West Africa ancestry, suggesting genetic heterogeneity in health risk factors in different African populations.

A European ancestry derived polygenic risk model for breast cancer explained only 0.79% of variance among these South African women, highlighting how different populations have different genetic influences on disease risk.

The authors conclude: “Larger studies in pan-African populations are needed to further define the genetic contribution to [breast cancer] risk.”

More on genetic studies:

“Scientists warn African DNA is missing from the global genome map” (RFI)

“Correcting for volunteer bias in GWAS increases SNP effect sizes and heritability estimates” (Nature Communications)

Further Learning

“Medical benchmarks and the myth of the universal patient” (New Yorker)

Manvir Singh argues WHO global child growth standards, largely based on people of European descent, can be incorrect for other genetic groups. He asks whether “universal” health metrics should be replaced by standards recognizing “human biological diversity” and “the different shapes of different populations.”

The author’s daughter was classified as “wasted” (malnourished) by WHO standards, despite appearing healthy and thriving.

Evolutionary anthropologist Herman Pontzer found that children of the Daasanach ethnic group in Kenya, who tend to be tall and lanky, were flagged for malnutrition, despite having normal behavior and health.

Singh recommends Pontzer’s Adaptable: How Your Unique Body Rally Works and Why Our Biology Unites Us for providing “an engrossing, richly informative exploration of human biological diversity.”

Singh argues the “universal” benchmarks can mislead health assessments and policy interventions. He cites discrepancies in child growth and malnutrition estiamtes across different regions.

“Take the so-called South Asian Enigma: India, Bangladesh, and Nepal exceed most sub-Saharan African countries on key health and development indicators, but their populations still fail to measure up (literally) to those in sub-Saharan Africa or the African diaspora. For instance, Haiti’s infant-mortality rate is almost twice that of India’s, and its per-capita GDP is 30% lower, yet only 6% of Haitian children are assessed as severely stunted, compared with 14% of Indian children.”

Singh writes: “We’ve entered the age of neurodiversity, precision medicine, and ‘bio-individuality,’ but we still assume that malnutrition looks the same in Cologne as it does in rural Kenya. Is it time to move beyond the model of the universal patient?”

The article highlights the importance of considering genetic and environmental factors in health standards, pointing out that human physiology is more diverse than commonly assumed by global health organizations.

More on human nature, evolution, and biotech:

“List of useful terms” (Not With a Bang): discusses concepts such as the Baby Boom Pattern, the Industrial Revolution Pattern, Everything Breaks in 1971/1973, the Great Awokening / Smartphones Pattern, J. D. UNwin’s Marriage Taxonomy, the Hajnal Line, Coffee Salon Demographics, the East Asian Exception, Clarkian Selection, Cognitive Capitalism, Nonlinear Ethnic Niche, the Signaling Theory of Education, and the Economist’s Fallacy

How CRISPR could enable safer food (Food Poisoning News)

“International bioethics, Ubuntu and HIV testing in Sub-Saharan Africa: an evaluation of Zambia’s HIV testing policy” (JoME)

“The table of Homovictimus: Artificial meats, biopolitics, and digital domination (SSRN)

Disclaimer: We cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect our own.