Repronews #80: Chinese births fall to lowest level since 1738

Rejuvenating ovaries | Durov’s >100 children | Confucianism & fertility goals | Lifespan 50% heritable | Mexican genetics, ancestry & disease | Genetics & schizophrenia | Qatari genetics | Inbreeding

Welcome to the latest issue of Repronews! Highlights from this week’s edition:

Repro/genetics

The Guardian reports on scientists who have “rejuvenated” human eggs for the first, potentially enhancing IVF success rates in older women.

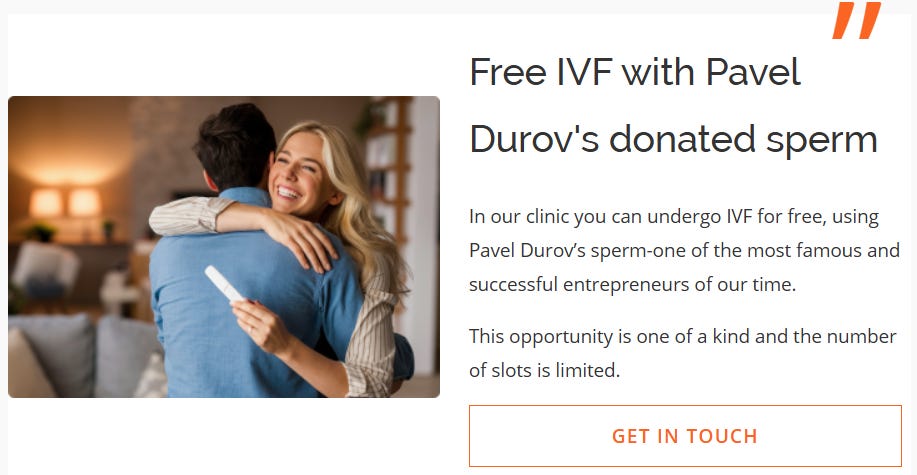

The Wall Street Journal reports that Russian Telegram billionaire Pavel Durov has had over 100 children by covering IVF costs for mothers and promising the children a share of his wealth.

Population Policies & Trends

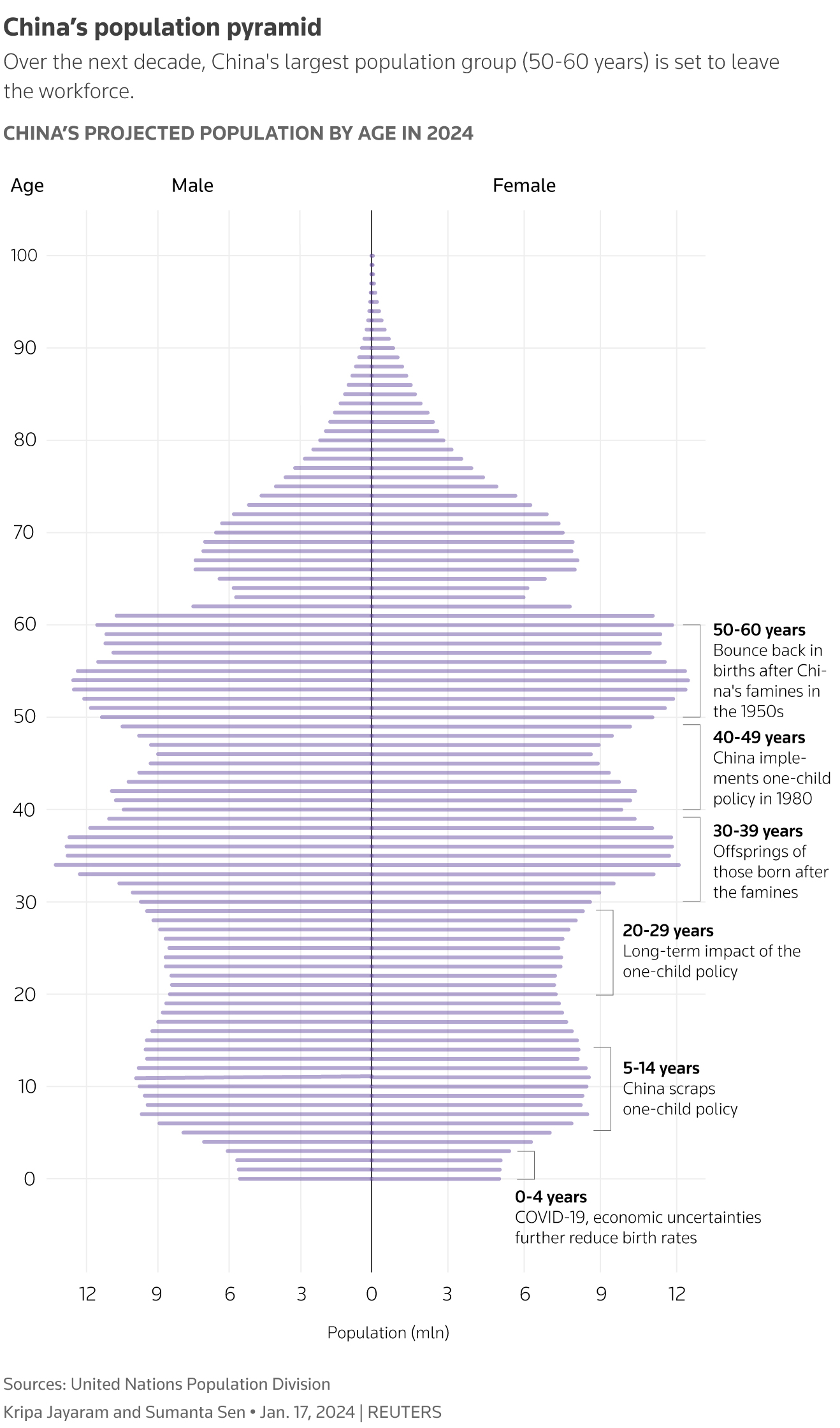

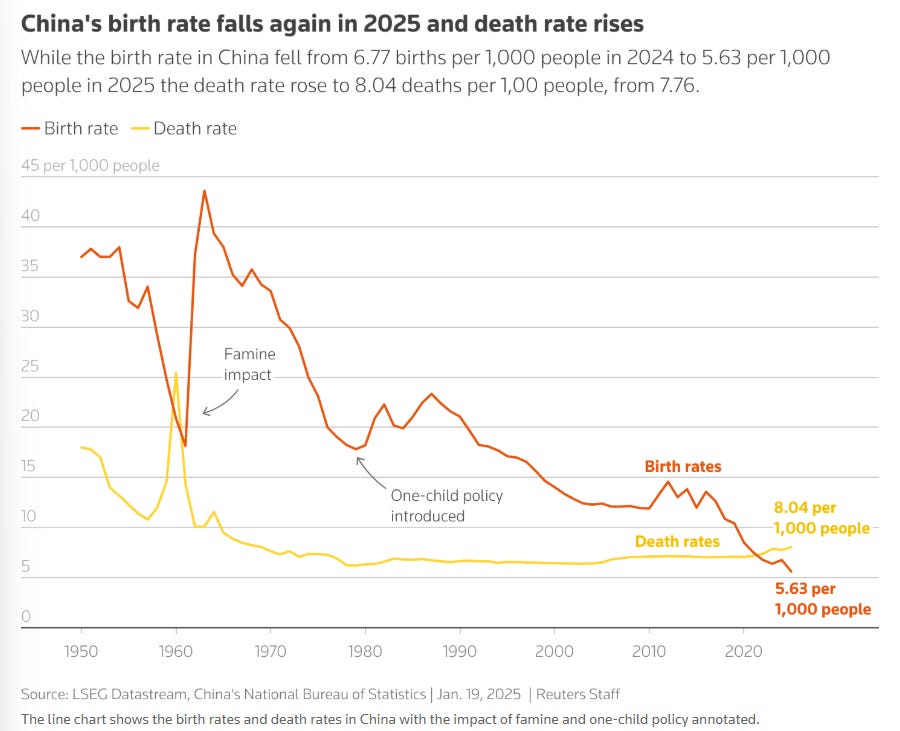

China’s population fell by 3.38 million in 2025; births fell to the same levels as 1738, when the population was about 10 times smaller.

Survey in Chinese city shows no correlation between support for Confucian family values and actual desire to have children.

Genetic Studies

The New York Times reports on a study suggesting that lifespan in over 50% heritable, with less influence of lifestyle than previously thought.

Genetic study of Mexicans shows significant racial heterogeneity of the population and differences in prevalence of genetic variants linked to various diseases depending on Native America, European, or African ancestry.

Largest study of schizophrenia in people of African ancestry finds over 100 new regions of the genome linked to the disease, highlighting the value of including broader genetic diversity in studies.

Qatari study maps genetic diversity of Arabs, highlights impact of inbreeding in disabling genes.

Further Learning

Francisco Ceballos writes in Quillette on the societal and health aspects of inbreeding, a phenomenon affecting 20-50% of marriages in certain societies.

Repro/genetics

“Human eggs ‘rejuvenated’ in an advance that could boost IVF success rates” (Guardian)

Scientists say they have “rejuvenated” human eggs for the first time, a procedure which could radically enhance IVF success rates for older women.

The research suggests that an age-related defect that causes genetic errors in embryos could be reversed by supplementing eggs with a protein. Eggs given microinjections of the protein were almost half as likely to show the defect.

Most women in their early 40s still have eggs, but most of these have an incorrect number of chromosomes.

Declining egg quality is the main reason IVF success rates fall sharply with female age and is why the risk of chromosome disorders such as Down’s syndrome increases with age.

“Overall we can nearly halve the number of eggs with [abnormal] chromosomes,” said Professor Melina Schuh, a Director at the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences in Göttingen and a Co-Founder of Ovo Labs, which aims to commercialize the technique. “That’s a very prominent improvement.”

In older eggs, chromosome pairs tend to loosen at their midpoint, becoming slightly unstuck or detaching entirely before fertilization. The X-shaped structures fail to align and instead move around chaotically in the cell. When the cell divided, this results in an embryo with too many or too few chromosomes.

In Britain, for patients under 35, the average birthrate for each embryo transferred in IVF treatment was 35%, compared with just 5% for women aged 43-44.

The average age of fertility patients starting treatment for the first time is over 35.

“Currently, when it comes to female factor infertility, the only solution that’s available to most patients is trying IVF multiple times so that, cumulatively, your likelihood of success increases,” said Dr. Agata Zielinska, a Co-Founder and Co-CEO of Ovo Labs. “What we envision is that many more women would be able to conceive within a single IVF cycle.”

The research must be confirmed in more extensive trials.

“A Russian billionaire fights global infertility—with 100 of his own children” (Wall Street Journal)

Pavel Durov, the billionaire founder of messaging app Telegram, has been covering IVF costs for women under 37 who want to use his donated sperm, promising his offspring a share of his fortune.

“The patients who came, they all looked great, were well-educated and very healthy,” said a former doctor at the IVF clinic offering the service, AltraVita. “They wanted to have a child from, well, a certain kind of man. They saw that kind of father figure as the right one.”

The women had to be unmarried to avoid legal complications.

Durov, now 41 and based in Dubai, said he has over 100 children in at least 12 countries, not counting six other children conceived with three different mothers.

“As long as they can establish their shared DNA with me, someday maybe in 30 years from now, they [the children] will be entitled to a share of my estate after I’m gone,” Durov has said. He plans to open source his DNA so that his biological children can find each other.

Forbes estimates Durov’s net worth at $17 billion.

Durov has framed his sperm donations as an effort to alleviate a shortage of healthy sperm and incentivize other men to do the same. He has attributed a “rapid drop in sperm concentration in men in many regions of the world” in part to plastic pollution, calling it a threat “to our survival.”

AltraVita also offers “selective” embryo screening for genetic diseases.

Anna Panina, a 35-year-old from Moscow, said she has considered participating in the program: “It’s a wonderful opportunity to become the mother of a beautiful and intelligent human being.”

More on repro/genetics:

“IVF embryo transfer: Natural ovulation proves as effective as hormone treatment, with fewer maternal complications” (Medical Xpress)

“Fertility and the workplace: Can employers help? Should they?” (PET)

Why these Indian women are breaking the law to sell their eggs for IVF (NPR)

“Consumer DNA test reveals truth about heritage” (PET)

“Bring on the clones: Conception and misconception” (Roger Gosden)

Population Policies & Trends

“China’s population drops for fourth year as fewer babies born” (Reuters)

China’s birth rate fell to a record low of 5.63 per 1,000 people in 2025.

The population fell for the fourth consecutive year, shrinking by 3.39 million.

In 2025, births were “roughly the same level as in 1738, when China's population was only about 150 million,” said Yi Fuxian, a demographer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The number of people aged over 60 has reached around 23% of the population, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

By 2035 the number of over-60s will reach 400 million, about the same as the populations of the United States and Italy combined.

China has increased retirement ages, with men expected to work until they are 63 rather than 60, and women until they are 58 rather than 55.

Marriages in China fell by 20% in 2024, the largest fall ever recorded.

Marriages are considered a leading indicator for births in China.

A May 2025 decision allowing couples to marry anywhere in the country rather than only their place of residence is likely to lead to a temporary boost to births. Marriages rose 22.5% from a year earlier to 1.61 million in Q3 2025.

Chinese authories are promoting “positive views on marriage and childbearing.”

China’s urbanization rate was 68% in 2025, up from 43% in 2005.

Population planning is central to China’s economic strategy. This year Beijing faces a total potential cost of around $25.8 billion to boost births, according to Reuters estimates.

Key costs are the national child subsidy, introduced for the first time last year, and a pledge that women throughout pregnancy have “no out-of-pocket expenses” in 2026, with all medical costs, including IVF, fully reimbursable.

The number of Chinese women of reproductive age—defined by the UN as women aged 15 to 49 —is forecast to fall by over two-thirds to less than 100 million by 2100.

“High Confucian Familism Adherence but Low Fertility Intentions: Evidence From the Lowest Fertility Rate City in China” (JoFI)

Yalei Zhai, a researcher at Kyoto University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies, found that in an ultra-low-fertility Chinese city, support for Confucian family values did not correlate with intention to have children.

The study estimates the impact of Confucian familism on fertility intention drawing from Tianjin Citizen Fertility Willingness Survey (n = 655 women, aged 15–49).

Although Confucian ideals that encourage childbearing are widely accepted, fertility intentions (i.e., the expected number of children) remain low.

Despite controling for fertility burdens and policy changes, stronger adherence to Confucian familism does not significantly predict greater fertility intentions.

Zhai concludes: “The results suggest that the inclination to have a single child, even under incentive-based birth policies, arises from an ultracompetitive society that lacks comprehensive social welfare guarantees.”

More on population policies and trends:

“I am a pronatalist” (Richard Hanania)

“Trump’s fertility care initiative: A step forward or a missed opportunity?” (PET)

Genetic Studies

“Genes may control your longevity, however healthily you live” (New York Times)

According to a study by the Weizmann Institute of Science (Israel), the human lifespan is about 50% heritable.

The New York Times writes: “You can lengthen [your lifespan] a bit with a healthy lifestyle. But if your genetic potential is to live to be 80, for example, it is unlikely that anything you do will push your age at death up to 100.”

The researchers used data from three sets of data from pairs of Swedish twins, including one set of twins that was reared apart, and data from a study of 2,092 siblings of 444 Americans who lived to be over 100.

The goal was to identify outside factors that can affect how long someone lives, like infections or accidents, but found a significant role for genes.

“If you are trying to gauge your own chances of getting to 100, I would say look at the longevity in your family,” said Dr. Thomas Perls, Director of the New England Centenarian Study.

“This paper has a pretty powerful message,” said S. Jay Olshansky, Emeritus Professor of epidemiology at the University of Illinois. “You don’t have as much control as you think.”

The study’s conclusions that genes are powerful drivers of lifespan is consistent with what is known about other species, said Daniela Bakula of the University of Copenhagen.

Dr. Uri Alon, one of the study authors, calculated that certain healthy or unhealthy habits can add or subtract 5 years or so from genetically expected life expectancy.

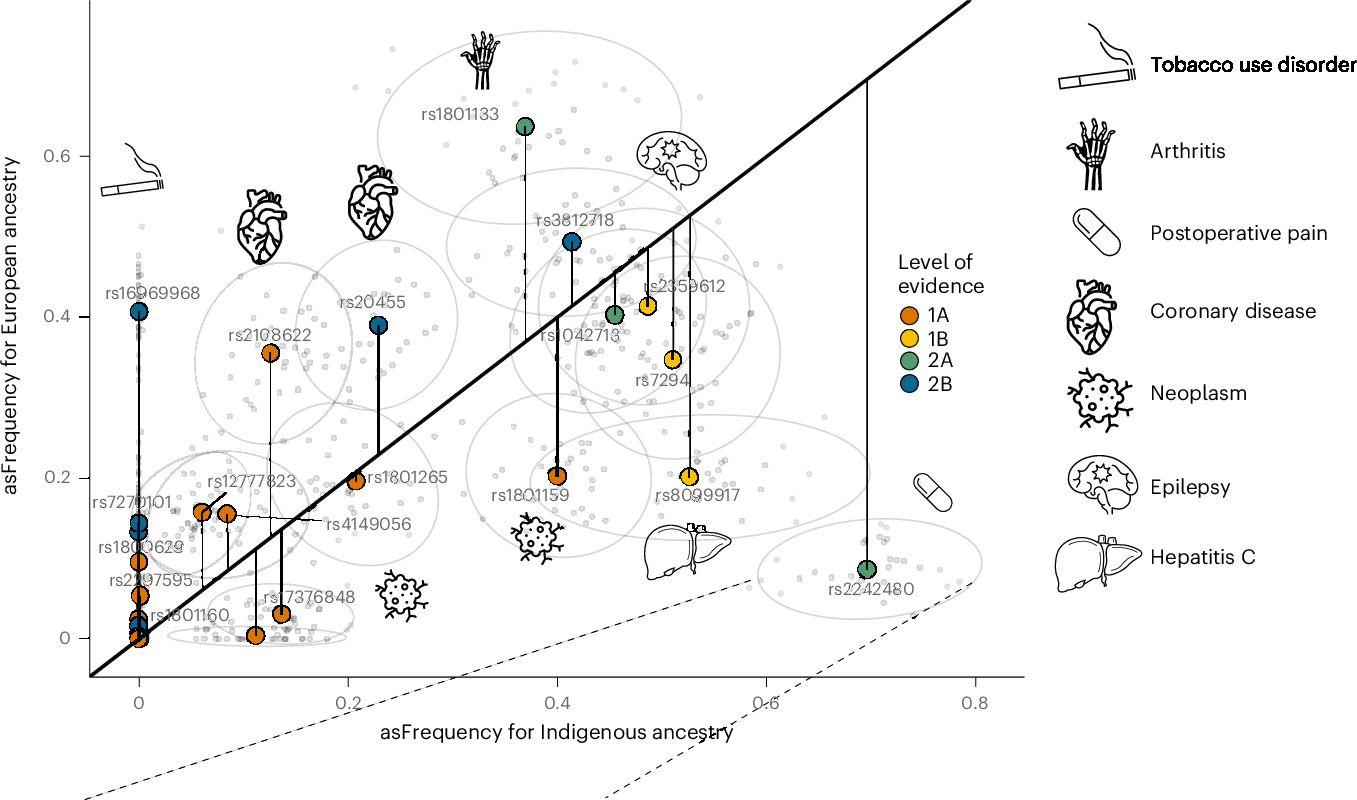

“Clinically relevant variants from the Mexican biobank show striking diversity across Hispanic people” (Nature Medicine)

Researchers at Cinvestav Research Center (Mexico City) analyzed genome-wide data for 6,011 people from Mexico and found that disease-relevant genetic variants were not uniformly distributed across ancestries, but differed according to European, African, or Native American genetics.

Te frequency distribution of gene variants that affect the metabolism of fentanyl (rs2242480) or statins (rs4149056) showed ancestry-specific patterns, being most prevalent in Native America ancestry chromosome segments.

The authors note: “The emerging population subgroups at risk could not have been detected without the incorporation of local ancestry in the analytical pipeline.”

There was also variation in disease risk within these broad ancestral categories, e.g. between northern and southern Mexican Indigenous groups.

The authors conclude: “This study illustrates genetic heterogeneity across Hispanic populations and demonstrates that disease risk varies widely within admixed populations. Thus, a ‘one size fits all’ population descriptor does not capture genetic differences in such populations, and a case-by-case approach should be used when investigating the genetic risk and distribution of clinically relevant genetic variants.”

The genetic risk patterns could inform public health measures and targeted genetic tests. Many of the differentiated variants show increased prevalence in Native American backgrounds.

“Largest genetic study of schizophrenia and African ancestry reveals shared biology across global populations” (Medical Xpress)

Schizophrenia and related psychoses occur in all human populations but have the highest rates of diagnosis among people of sub-Saharan Africa ancestry.

Decades of research have established a highly heritable and polygenic basis for schizophrenia, which is mostly shared across populations.

Electronic health records linked with genomic data from the Million Veteran Program (MVP)—a U.S. research program that looks at the effects of genes, lifestyle, military experiences, and exposures on the health and wellness—enable a comprehensive assessment of schizophrenia genetics in populations of African ancestry in the U.S.

The researchers found over 100 new regions in the genome linked to schizophrenia that had not been clearly identified before. Many of these genetic differences are more common in people of African ancestry.

People of African ancestry have been under-studied in genetic research.

“Qatari genetic map reveals over 150,000 structural variants” (Medical Xpress)

Research by King’s College London and Sidra Medicine, Qatar, has produced the most detailed map of large-scale genetic differences in the Qatari population, revealing providing a clearer picture of the genetic diversity of Arabs and the relationships between genetic variations and health.

People of Arab ancestry remain significantly underrepresented in large global databases of human genomes.

The research looks at structural variants—large-scale changes in DNA that affect long stretches of genetic material that can be missing, duplicated, or rearranged. Because of their size, structural variants affect much more of the genome, making them relevant to human health.

The researchers analyzed more than 6,000 Qatari genomes. allowing them to see where variants occur, how common they are across the five main Qatari sub-populations, and their relationship to health information from the Qatar Biobank.

The analyses revealed over 150,000 structural variants. Many affected genes are involved in biological processes related to cardiometabolic health and diabetes, aligning with the high prevalence of related diseases in the population.

“Structural variants have an important impact on human biology, but they’ve been largely understudied in global genomics because they’re hard to detect,” said Dr. Mario Falchi, Reader in Computational Medicine at King’s. “We’ve created the most detailed map of these variants in the Arab population. This gives us a much clearer view of genetic diversity in the region and paves the way for precision medicine.”

High levels of consanguinity (inbreeding) enables examination of the impact of inheriting deletions of pieces of DNA from both parents. The researchers uncovered more than 180 genes that had lost their function completely or been “knocked out” as a result of inheriting the same deletion from both parents. This means the protein associated with the gene is not produced at all.

There were certain regions of the genome where the loss of both copies of DNA was not seen, despite the frequency of people in the population who carried the same deletion, suggeting having at least one copy is essential for human survival,

“This work is presented both as a unique global resource for anyone studying the genetics of Arab ancestries around the world, and as a demonstration of the importance of consanguineous populations in improving our understanding of the human genome,” said Professor Khalid Fakhro, Chief Research Officer and Lead Principal Investigator of the research study at Sidra Medicine. “We look forward to expanding these studies to tens of thousands of Qatari genomes in the next phase, and to contribute to global efforts in genetic mapping and population-scale health discovery.”

The Qatar Genome Program has played a pioneering role in including Arab genomes in global genomic databases with detailed health information from more than 40,000 Qataris collected through the Qatar Biobank.

More on genetic studies:

“Large study identifies more than 100 genetic regions linked to schizophrenia” (News Medical)

“Maternal genetic factors may reveal why pregnancy loss is so common” (Medical Xpress)

“Big data make hidden genetic drivers of type 2 diabetes visible” (Medical Xpress)

“Genetic variants associated with rare inherited growth disorder identified in two prehistoric individuals” (News Medical)

“National genomic screening program could save thousands of Australians from preventable cancer and heart disease” (Medical Xpress)

“Genomic screening uncovers hidden cancer and heart disease risk in young adults” (News Medical)

Further Learning

Francisco Ceballos, “A brief history of inbreeding” (Quillette)

Biologist Francisco Ceballos writes that while inbreeding can provoke strong moral and cultural reactions, but it is a biological reality that can be measured precisely with modern genomics.

The main forms of inbreeding are:

Endogamy by isolation: small, geographically isolated populations intermarry out of necessity (genetic drift).

Consanguinity by choice: deliberate marriage between relatives for social, economic, or symbolic reasons (property, lineage, trust).

Many societies practised consanguinity for political or social reasons (royal dynasties, clans, religious communities), often to preserve status or cohesion.

Genomics revealed a key marker of inbreeding: runs of homozygosity (ROH) — long stretches of identical DNA inherited from both parents.

Everyone has some ROH because humans ultimately descend from small ancient populations. The longer the ROH, the closer the parental relatedness.

Ancient humans were often highly inbred due to small, scattered populations. With agriculture, trade, and migration, human genetic diversity increased and inbreeding declined. Some cultures reintroduced consanguinity deliberately.

Inbreeding increases the risk of congenital diseases: while everyone carries hidden recessive mutations, children of relatives have a higher chance of carrying the same mutation in their chromosome pair.

This results in higher rates of recessive genetic diseases and inbreeding depression (reduced overall vitality affecting height, fertility, immunity, cognition, and survival).

Darwin first demonstrated inbreeding depression experimentally in plants.

Historical examples like the Habsburg dynasty illustrate how repeated consanguinity weakens populations over generations.

Modern genomic studies show measurable health impacts of cousin marriage: Higher child mortality, more learning disabilities and developmental delays, greater healthcare use, and higher rates of congenital disorders.

These effects are observed even in wealthy societies with good healthcare, indicating the cause is genetic, not environmental.

About 10% of people worldwide descend from consanguineous unions. In some regions 20–50% of marriages are between relatives.

Ceballos argues this makes consanguinity not only a private or cultural matter, but a public-health and economic issue due to higher medical and social costs.

The topic is politically sensitive, often leading to reluctance to discuss risks openly. Genetics is about probabilities, not moral judgment.

Ceballos concludes that just as genetic inbreeding reduces biological resilience, intellectual or cultural inbreeding reduces societal resilience. Diversity—genetic or intellectual—supports robustness.

More on human nature, evolution, and biotech:

“The mysterious eugenics of aesthetic taste” (Los Angeles Review of Books)

Disclaimer: We cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect our own.