The CRISPR crop revolution crashes Europe

EU moves to liberalize gene-edited crops to boost sustainability and food security

Over at Quillette, Steven Cerier and Jon Entine, contributors to the Genetic Literacy Project, provide an overview of recent developments in the European Union on allowing marketing of genetically-edited crops (notably CRISPR crops).

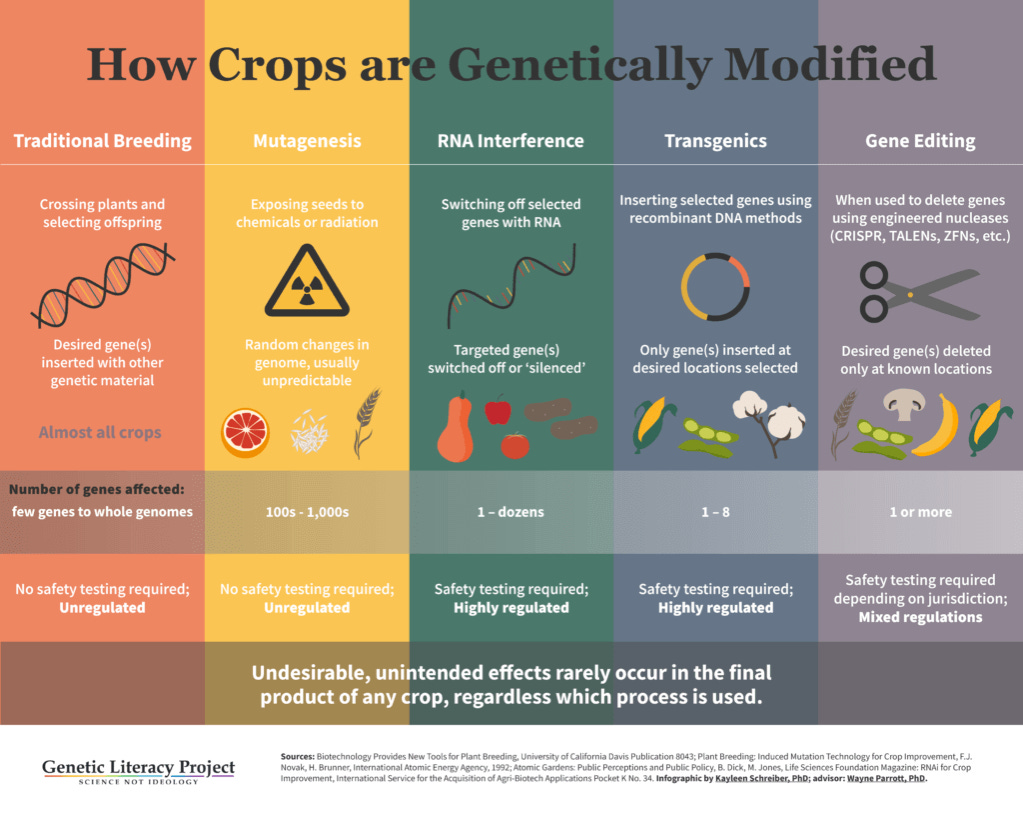

Why is this happening now, particularly given how hostile many European countries are to GMOs? Traditional GMOs are the result of the transposition of a gene from another organism rather than a simple gene edit. By contrast, the new gene-edited crops have a more precise genetic modification—such as changing a single letter of DNA—of the kind which spontaneously commonly occurs in nature through mutation. Indeed, there is currently no way to distinguish gene-edited organisms from naturally mutated organisms. This can enable to creation of crops that are more climate-resilient, more productive, or less dependent on pesticides. In addition, most other major economies allow or are moving towards marketing of gene-edited crops.

All this has put pressure on the EU to respond in some way to the new possibilities of CRISPR crops. As often, Eurocrats are caught in a bind. On the one hand, the technocratic European Commission has structured recourse to scientific expertise and therefore has tended to support biotech as far back as its 2002 Strategy on Life Sciences and Biotechnology. On the other hand, EU-level lawmaking is inevitably a highly consensual affair requiring overwhelming support among the 27 national governments—and many of these have been very hostile to GM crops and food, not least major countries like Germany, France, and Italy. Compared with both the United States and China, Europe has a broadly risk-averse regulatory culture enshrined in the Precautionary Principle.

With other nations embracing CRISPR crops and scientists touting the environmental and nutritional benefits, Brussels is moving forward. Last year, the European Commission proposed a Regulation to liberalize gene-edited crops created through New Genomic Techniques (NGTs, including CRISPR). In its preface to the draft law (which, by the way, is a great place to start for understanding the Commission’s rationale, evidence base, and trade-offs for any new piece of legislation), the Commission noted that gene-edited crops include

plants with improved tolerance or resistance to plant diseases and pests, plants with improved tolerance or resistance to climate change effects and environmental stresses, improved nutrient and water-use efficiency, plants with higher yields and resilience and improved quality characteristics.

The EU Commission further argues that these “types of new plants, coupled with the fairly easy and speedy applicability of those new techniques, could deliver benefits to farmers, consumers, and to the environment.” The EU’s executive arm also stresses the risk to the EU’s competitiveness and strategic autonomy, especially food security:

The Union risks being excluded to a significant extent from the technological developments and economic, social and environmental benefits that these new technologies can potentially generate, if its GMO framework is not adapted to NGTs. … The Union seed sector is the largest exporter of seeds in the world and the ability to use innovative technologies is a prerequisite to maintain competitiveness on the global market. This proposal is also expected to have an impact on strategic autonomy and resilience of the Union food system, as NGTs are expected to be applied to a large range of crop species and traits by a diverse set of actors.

Having been following the emergence of CRISPR for some years, I have been wondering for a while how life scientists’ general support for the safety and use of gene-edited crops and animals would eventually collide with anti-GM NGOs and opinion in Europe.

Cerier and Entine give a detailed rundown of recent developments in this field:

The EU imports transgenic GMO seeds, mostly for use as animal feed, but letting farmers grow such crops is largely banned.

On 6 February, the European Parliament voted (301 to 263) to adopt its amended version of the NGTs Regulation which would make it far easier for farmers to grow and for consumers to eat the new generation of genetically engineered food.

In 2015, a Pew poll of American scientists found that 88% said GMO foods are generally safe to eat (compared with only 37% of the public).

NGT products have been approved in different countries, including:

Late-blight resistant, low acrylamide, and reduced-bruising potatoes

Non-browning apples

Drought-resistant wheat

Insect-resistant cowpeas (a major staple crop in west Africa)

A purple tomato with increased anti-oxidants and a longer shelf life

Mustard greens that are less bitter

A heart-healthy tomato

Fish oil made from canola

Pigs that are resistant to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome

Many more products are in the genetic-engineering pipeline, including:

Disease-resistant bananas, citrus crops, and chestnuts

China is determined to be a global CRISPR innovator. In 2022, China announced it was deregulating crop gene editing. Last year, the government preliminarily approved 37 genetically modified corn seeds and 14 GM soybean seed varieties. In January, China authorized the domestic production of six additional varieties of GM corn, two varieties of soybeans, one variety of cotton, and another two varieties of gene-edited soybeans.

The top eight most populous countries representing more than 50% of the world’s population—China, India, the United States, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Brazil, and Bangladesh—now either grow GMO crops or have approved the deregulation of gene-edited crops.

Food-exporting countries are also embracing NGTs, notably Brazil and Argentina. Africa is also gradually opening its doors to crop technology innovation, with GMO laws in place in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Ghana, Zambia, and South Africa.

In March 2023, the British Parliament deregulated gene editing within England.

The authors argue anti-GMO activists’ claims that the products increase cancer and infertility and damage the environment have not panned out.

It takes an average of eight to 13 years and more than $130 million to get a GMO-crop trait approved in the United States.

It can now cost just a few million dollars and two years or less to develop a crop with a beneficial new trait. One faculty researcher at Penn State developed an anti-browning mushroom for less than $50,000.

Under the European Parliament’s version of the legislation, most gene-edited plans will require labeling and will not be classifiable as “organic,” even if grown without use of pesticides.

The text would also requires the tracing of gene edits, which is impossible with current technologies, and forbid patents on NGTs.

The law still needs to be approved by countries representing at least 65% of the EU’s population in the Council of the EU.

It is unclear whether national governments in the Council will be able to find an agreement in before the EU parliamentary elections in June. In any case, once Council has its position, a common position with Parliament will have to be reached through “trilogue” negotiations (so-called because the Commission also participates in the talks) and then adopted by both bodies.

Many biotechnologists are critical of the Parliament’s draft legislation: the provisions on patents, traceability, labeling, and lack of organic certification, they say, risk making crop innovation uneconomical. Nonetheless, this represents a major shift away from the EU’s traditional bioconservative regime on crops and may herald a broader shift in the bloc’s attitudes towards biotech.