China vs. U.S.: Who will win the U.S.-China scientific race?

“Nature” notes Chinese R&D funding will overtake U.S. by 2030, while U.S. retains global lead in brain gain

Nature has a good summary article with some nice graphs outlining the United States’ prospects in the face of the scientific rise of China. While still a top scientific performer, the U.S. is already being beaten by China on some metrics. Quote:

Science in the United States has never been stronger by most measures.

Over the past five years, the nation has won more scientific Nobel prizes than the rest of the world combined—in line with its domination of the prizes since the middle of the twentieth century. In 2020, two U.S. drug companies spearheaded the development of vaccines that helped to contain a pandemic. Two years later, a California start-up firm released the revolutionary artificial-intelligence (AI) tool ChatGPT and a national laboratory broke a fundamental barrier in nuclear fusion.

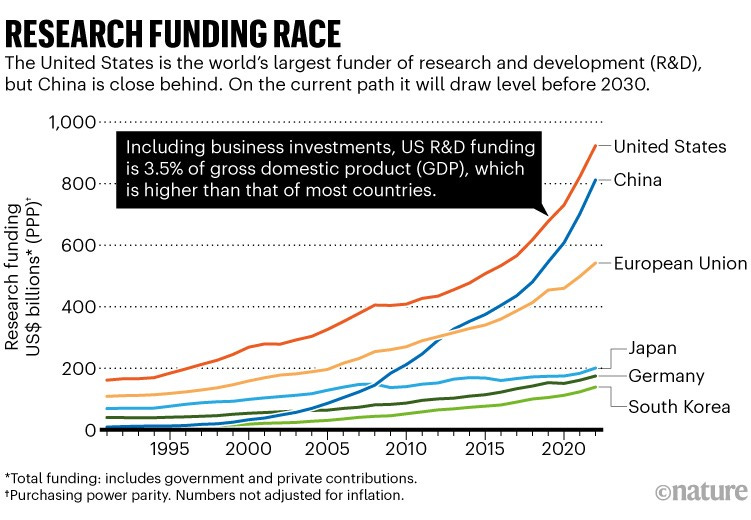

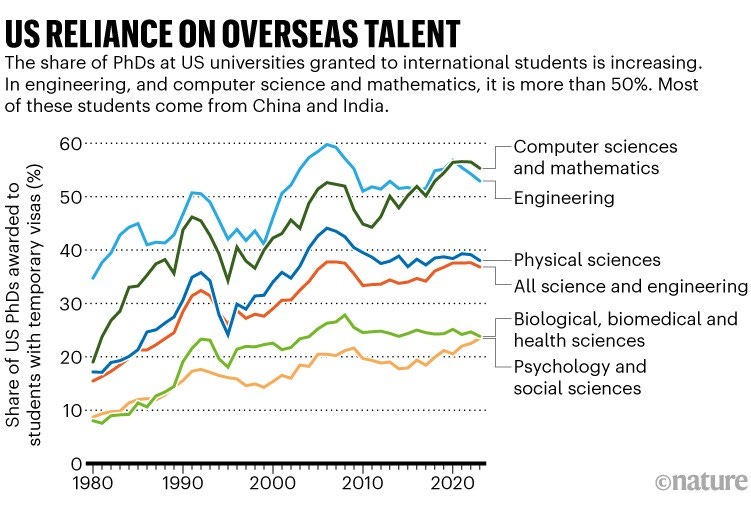

This year, the United States is on track to spend US$1 trillion on research and development (R&D), much more than any other country. And its labs are a magnet for researchers from around the globe, with workers born in other nations accounting for 43% of doctorate-holders in the U.S. workforce in science, technology, engineering and medicine (STEM).

But as voters go to the polls in November to elect a new president and Congress, some scientific leaders worry that the nation is ceding ground to other research powerhouses, notably China, which is already outpacing the United States on many of the leading science metrics. “US science is perceived to be—and is—losing the race for global STEM leadership,” said Marcia McNutt, president of the US National Academy of Sciences in Washington DC, in a speech in June.

Chinese R&D funding is set to catch up with the U.S. before 2030:

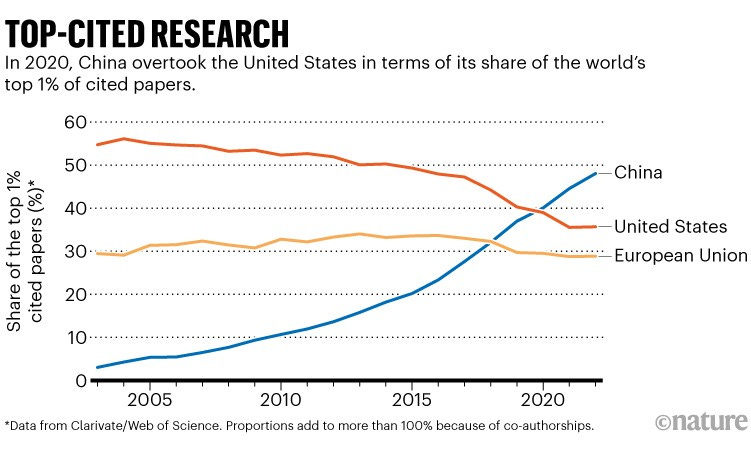

China now has more scientists, scientific publications, and patents (annually) than the U.S. Crucially, contra to those who believe the Chinese are gaming the system with low-quality publications and patents, China has been producing the most top-cited papers in the world since 2020.

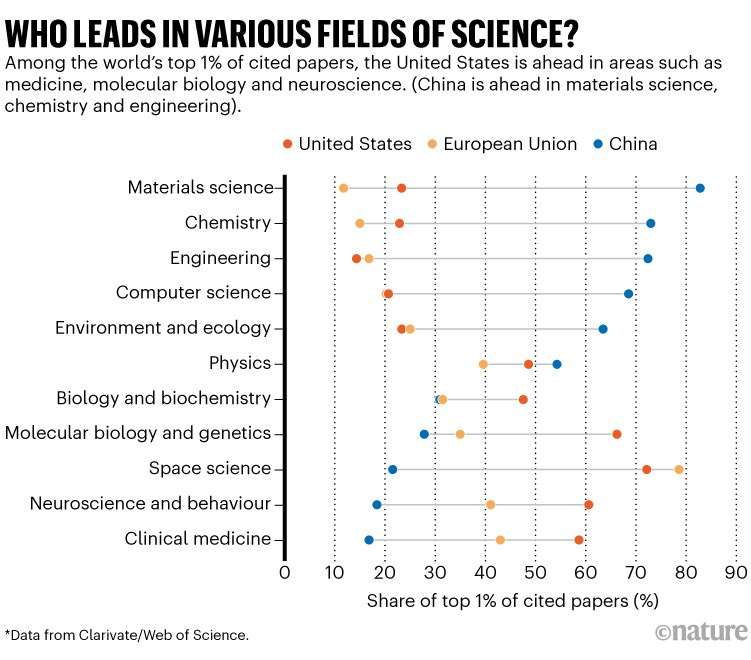

Chinese scientists are espcially dominant in chemistry, engineering, and computer science, performing less well in space and the life sciences.

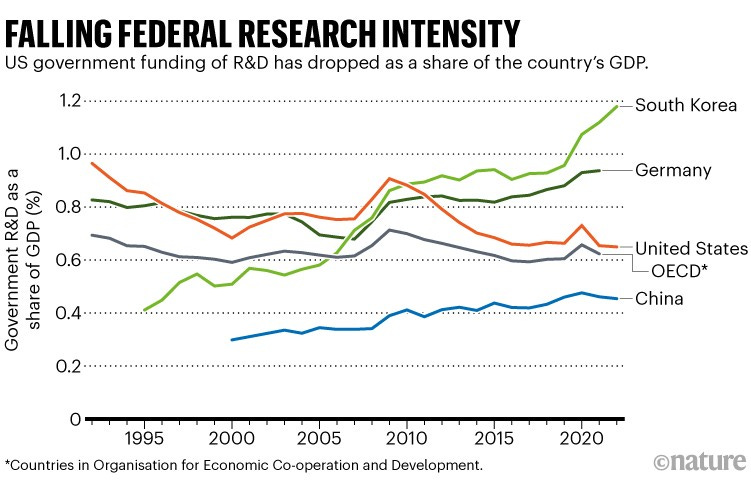

U.S. government funding for R&D is declining. However, overall U.S. R&D spending as a percent of GDP is still growing thanks to increased investment by the private sector. U.S. R&D spending was 3.46% of GDP in 2021, compared with 2.28% in the European Union and 2.43% in China. It is noteworthy that Chinese government spending on science is low.

America’s reliance on (mostly Asian) foreign talent in science is massive, with one third of science and engineering PhDs going to international students, including 59% of computer science students. For a variety of reasons, there is no chance China will be able to replicate this kind of brain gain, though there is a growing number of international students in the country.

In fact, Chinese students are the top contingency among international students in the U.S.. Among Chinese who earned a PhD in the U.S., 77% say they want to stay (2022 figure, only slightly lower than previous years). The U.S. hosted 15% of all international students worldwide in 2020, down from 23% in 2000. In absolute terms, the post-COVID U.S. is hosting the most international students ever.

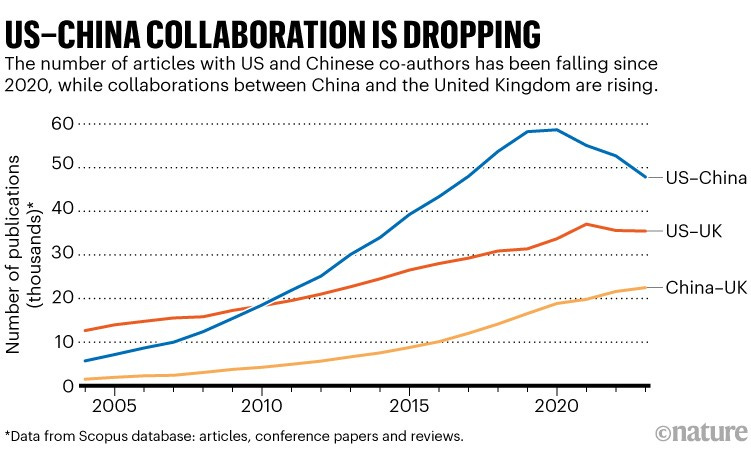

U.S.-Chinese research collaborations are falling fast, reflecting American fears about Chinese power. Lee Kuan Yew, the late prime minister of Singapore, observed from his own experience that the Chinese have often viewed partnerships more as a way of securing foreign IP rather than collaboration per se.

The authors of the Nature article believe the imminent U.S. elections will be important for the future of science in the U.S. For me, it it is no so clear what a victory of either side would mean. The White House either under a Trump 2 or a Harris Presidency will want the U.S. to remain competitive in cutting-edge fields like computer chips, AI, biotech, and space.

As the article notes, Congress, not the president, often has the final say on federal science policy. Republicans are warier of ties with China but Democrats have often come to share their concerns. Republicans are more hostile to stem cell research. While Democrats may be generally more favorable to (non-military) federal funding for science, the Trumpian agenda of tax cuts and deregulation could invigorate private sector R&D, which is arguably where the U.S. has a decisive edge (in tech, AI, biotech, pharma, space…).

In any case, these trends are suggestive of just how positive the impact of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s embrace of capitalism from 1979 was. In less than two generations, the conversion to a market economy enabled the Chinese to go from a hungry economic backwater to a scientific peer of the United States.

Whether China can lastingly overtake the U.S. is perhaps less clear. On the one hand, China’s working-age population—and therefore the future pool of potential scientists and engineers—is already collapsing and the country is unlikely to be able to compensate for this with brain gain. On the other hand, if Chinese per capita scientific performance becomes similar to, say, South Korea, that alone may be sufficient for China to have as much scientific output as the U.S. and Europe put together.

In any event, we shouldn’t see science as zero-sum international game. Science, the pursuit of knowledge, is a universal human pursuit whose benefits often, and should, redound in some way to all humanity.

Government spending on research is a very poor metric. It looks only at expenditure, not results. A comparison of private investment in research in both countries would be a bit more illuminating. The US would come out better, I expect, although the US also spends a lot on wasteful government research.

As a Nature subscriber, I have noticed its drift from scientific reporting to propaganda, and this article was an example. In real (scientific) life, China leads the US in virtually every field of research and application, both in the number of peer-reviewed papers and in their quality. Of the world's top twenty research institutions, seven are Chinese and one is American, for example.

China outspends the USA fourfold on R&D, which should be obvious to anyone who keeps up with Big Science. The PRC spends 2.6% of its $35 trillion GDP on it, compared to 0.8% of our $25 trillion GDP. Chinese corporate R&D–as we see in results from Huawei, BYD and CATL–is similarly ahead of ours.

Nature, like the Federal Reserve, is simply extending the pretence that we are Number One.