5 Mega-Trends Defining Europe’s 21st Century

Demographics, science & disparities

In the rough-and-tumble of day-to-day news and government, it’s easy to lose sight of the big picture. We often can’t see the forest for the tees. But policymakers and citizens need to have the big trends in view, to be far-sighted, if their daily action is to be meaningful and wise in the long-run. With that in mind, here are five mega-trends, epoch-defining tendencies, that will massively impact Europe in the twenty-first century. Some are well-known, while others deserve to be.

Mega-trend #1: Europe’s relative decline and need for unity

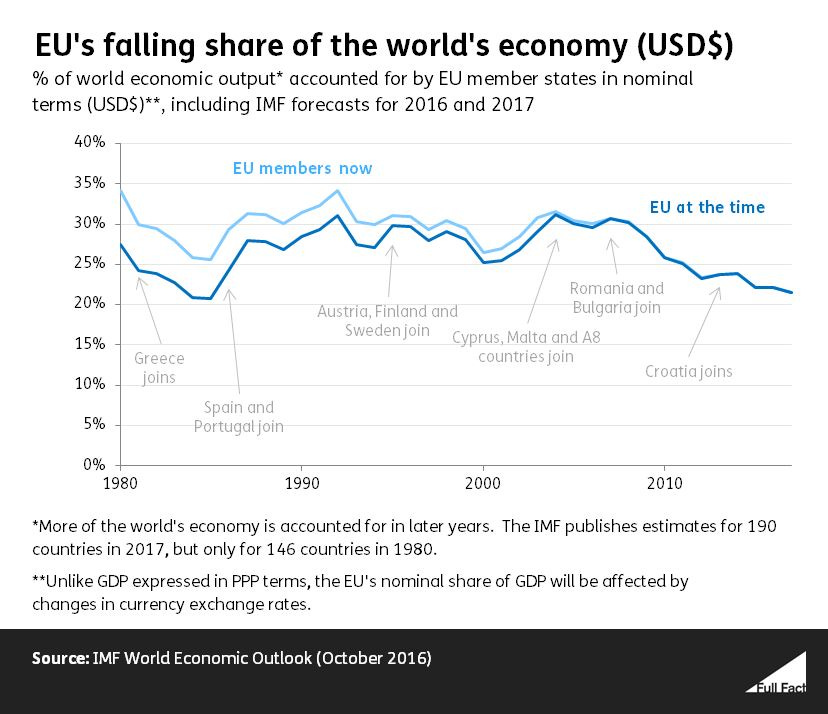

The first fact to come to grips with is Europe’s shrinking share of global GDP, especially since the 1980s. While Europeans enjoy a high standard of living by global standards - the European Union’s GDP/capita is about three times the global average - relative economic decline mechanically follows from the Old Continent’s declining share of the global population and the partial upward convergence of standards of living in the rest of the world (specifically, East Asia is steadily equalizing or surpassing Western standards of living, while most of the rest of the world falls into the so-called “middle-income trap,” see Mega-trend #5 below).

The EU’s declining economic weight has been partly compensated by successive waves of enlargement in southern and eastern Europe. Conversely, Brexit represents a significant blow given that Great Britain was the bloc’s second-largest economy. According to World Bank data for 2020, the EU’s nominal GDP was worth $15.3 trillion, significantly below the United States’ $20.95 trillion and about to be overtaken by China’s $14.7 trillion.

This trend makes it all the more important for Europe’s nation-states to cooperate and join politically if they are to maintain or restore their influence, sovereignty, and power. The EU is likely to retain a dominant economic influence in its own neighborhood of North Africa, the Western Balkans, and Eastern Europe. The only neighboring states with serious geopolitical capacity are Turkey and Russia, and the latter is facing a similar demographic decline.

Mega-trend #2: The scientific rise of China

As reasonably proxied by the Nature Index, scientific achievement today is sharply concentrated in North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. While China’s scientific output is rapidly catching up with the West, the rest of the world’s performance is almost negligible and, outside a fraction of India, will likely remain that way.

It is noteworthy that major European nations - including France, Italy, and Spain - appear to be declining in scientific importance relative to China and the Anglosphere, at least as measured by academic publications. On the other hand, many northern European universities are rising in prestige and influence. All this makes it all the more important for the EU to intensify and pool its scientific efforts. With its human capital and scale, Europe is already a world-leader in aerospace and various efforts are underway to catch up with the US and China on IT, semiconductors, AI, and biotech. (Pro-tip: Science|Business is an excellent and insightful source on Europe’s scientific and technological policies and activities.)

Mega-trend #3: Exponential Africa and the decline of the scientific world

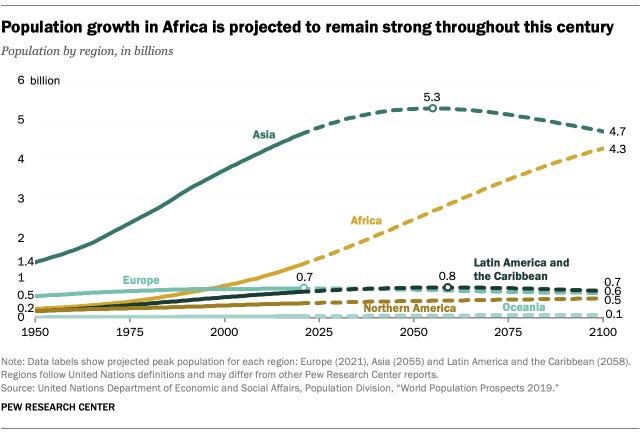

Demographics is the elephant in the room. Climate change, AI, nuclear fusion, wars, régime collapse, pandemics: the eventuality, impact, timing, and scale of all these phenomena are extremely difficult to gauge. Medium-term demographics however are easy to predict: today’s births are tomorrow’s adults. The first great demographic fact of the twenty-first century is the exponential growth of Africa. According to UN forecasts, Africa’s population will grow from 811 million in 2000 to 4.3 billion in 2100. As Adam Tooze has argued: “The sheer scale of Africa’s demographic acceleration makes it a vastly significant megatrend.”

That Africa is on a solid growth curve is seen by the fact that the continent in 2020 was estimated to have 1.3 billion people, thus increasing over the previous two decades by almost 500 million, more than the entire population of the EU. Nigeria alone is expected to have 733 million in 2100, while Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo will more modestly have 294 million and 362 million respectively.

Of course, forecasts to 2100 remain approximative. Still, any growth of this order of magnitude will be certain to lead to enormous socioeconomic and environmental pressures. One can easily imagine the (re-)ignition of civil wars (currently ongoing in Ethiopia and eastern Congo) on an even vaster scale. Enormous ongoing migratory pressure, which Europe has struggled to deal with for over a decade, is likely to intensify. French President Emmanuel Macron was right in pointing out that African development and migratory issues can only be tackled if fertility is reduced.

The second great demographic fact will be the decline and aging of all nations significantly contributing to global science and innovation (see Mega-trend #2). Jonathan Haidt has suggested that atheism may be so evolutionarily maladaptive as to be biologically unsustainable:

Societies that forgo the exoskeleton of religion should reflect carefully on what will happen to them over several generations. We don’t really know, because the first atheistic societies have only emerged in Europe in the last few decades. They are the least efficient societies ever known at turning resources (of which they have a lot) into offspring (of which they have few).1

While Europe’s demographic situation is by no means rosy (see Mega-trend #4), it so happens that most East Asian nations, who have equalized or surpassed European standards of living, now have even lower fertility, the lowest in the world.

According to the World Bank, these were the total fertility rates in East Asia in 2020: China 1.7, Japan 1.34, Taiwan 1.22, Singapore 1.1, Hong Kong 0.87, South Korea 0.84. A major reason for this appears to be out-of-control credentialism (e.g., in South Korea it is not unusual for students to study at high-school and after-school classes for 12-16 hours per day and 71.5% of young people enroll in higher education).

The developed nations in North America, Europe, and East Asia will make up a shrinking proportion of humanity and will be increasingly possessed by their internal demographic problems, namely caring for a huge proportion of elderly and, as the case may be, ethnic and religious conflicts. The decline in fertility has continued to worsen during the COVID crisis. As a result of these trends, it is likely developed nations will have considerably less energy to expend outwards.

This is significant as the developed world is responsible for producing innumerable transnational and global goods: international aid, remittances, a favorable economic and political climate (a responsibility developed nations admittedly fail to live up whenever they embrace a destabilizing and/or bellicose foreign policy), and, especially, transferable science and technology.

Further technological advances will likely to be necessary to overcome our planet’s environmental challenges. Remaining at the current level of technology, environmental problems would continue to worsen as populations and standards of living rise in Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. The EU’s efforts to decarbonize its economy by 2050 is chiefly significant as an example to others. In 2020, the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions were estimated at 1.94 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent. That’s five times less than China, less than half the United States, and already less than India. One study found that 88-94% of plastic dumped into the oceans from rivers came from 10 rivers in Asia and Africa. The ability to solve such disasters will depend crucially on the ability of scientifically productive nations to create and share critical innovations.

Mega-trend #4: An older, more diverse, more uneven Europe

Moderate-to-severe developmental and demographic disparities between Europe’s nations and territories risk becoming entrenched. Simplifying, southern and especially eastern European nations will decline in population due to low fertility rates and emigration, reinforcing the position of “core” and northern Europe.

Some cases are extreme: Eurostat expects that Bulgaria’s population will decline from almost 7 million in 2020 to 5.65 million 2050, Romania from 19.3 million to 15.5 million, and Poland from almost 38 million down to 34.1 million (admittedly, this estimate was before the recent influx of Ukrainian refugees).

Within Western Europe, many rural and peripheral territories are also witnessing population decline. Eurostat forecasts that two-thirds of all regions in the EU will lose population between now and 2050.

In a recent release entitled “EU births: decline continues, but not from foreign-born women,” Eurostat revealed that southern Europe now has the continent’s lowest fertility rates: Portugal 1.43, Greece 1.34, Cyprus 1.33, Italy 1.27, and Spain 1.23. Combined with emigration, exacerbated by weak economic performance in the wake of the euro crisis, southern Europe’s demographic prospects don’t look good.

Overall the EU population is forecast to be reasonably stable, going from 447.7 million in 2020 to 441.2 million in 2050. This population will however be older - the dependency ratio will increase substantially and the median age will rise from 43.7 to 48.2.

Some EU institutions have been raising the alarm on these demographic challenges. The Committee of the Regions, representing the EU’s local and regional governments, has raised the issue of brain drain afflicting many territories. Emil Boc, the mayor of Cluj-Napoca in Romania, presented the Committee’s position saying: “The task of cities and regions is to develop innovative policies to retain and re-attract talents. Enhancing quality of life is a very powerful tool for attracting and retaining an educated workforce.”

The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), representing civil society organizations, has argued that “Immigration alone might not be the solution to Europe's demographic challenge” and that fertility rates should be increased through “stable and proactive family policy and human-centred labour market policies.”

While many European and East Asian countries have natalist policies in place, these appear largely ineffective. Israel is apparently the only exception. Remarkably, the Israeli Jewish fertility rate is now higher than the Arabs’, contradicting longtime predictions of the Jewish state’s inevitable demographic submersion.

Contemporary natalist policies are generally purely quantitative in approach. It is not that governments are unaware of the crucial importance of the qualitative aspects of human capital, but their policies in this area are largely restricted to poaching “talent” (highly-skilled/educated individuals) from other countries through attractiveness. Given that intelligence and other pro-social traits are significantly heritable, this “brain drain” approach is effectively parasitic, worsening territorial and international disparities and undermining other societies’ ability to flourish.

Mega-trend #5: Enduring international and intra-national disparities

It seems fair to say that 1990 to 2015 represented an era of optimism for internationalism and liberal-egalitarian values. While some predicted the transcendence of the nation-state (in both its components), few would be so bold today. Globalization will not be wholly unwound however as many of its drivers are beyond the control of all but the most totalitarian states. (How well will North Korea and Afghanistan insulate themselves from outside trends?)

However, a core tenet of liberal globalization has become untenable: the assumption of an eventual full or even approximate economic convergence between nations. Instead, once a market economy and basic stability are established, a nation seems to converge to and fluctuate around a certain level of relative economic performance, reflecting its basic ability to import, replicate, and/or apply cutting-edge technologies and organizational models.

A nation’s relative economic level will certainly fluctuate with long-term industrial cycles, exchange rate fluctuation, political instability, and choice of economic policies. However, the long-term rankings and relative performance, once basic stability and markets have been allowed to do their work, are striking in their stability. Latin America continues to underperform despite long centuries of independence.2 By contrast, in the postwar era East Asian nations have, within years of adopting capitalism, modernized at break-neck pace. East Asia is steadily achieving first-world status and equalizing or even surpassing Western standards of living. The default scenario for others regions is the notorious “middle-income trap.”

Relative performance likely reflects deep human and organizational factors. Among major economies, the exceptional per capita performance of the U.S. for example seems to reflect certain American advantages, such as the size of the domestic market, the dollar’s status as an international reserve currency, the sheer scale of brain drain to the U.S., and the flexibility and drive of American workers and entrepreneurs.

The upshot of all this is the likelihood of lasting and stable disparities. Convergence optimists have been wrong for the last 60 years. Why assume they will be right for the next 60? In addition to disparities between nations, it is noteworthy that there are also similarly entrenched disparities between territories and ethnic groups within nations.

What does this mean for Europe?

Mega-trends are not always inevitable: some predictions turn out to be false and even the most deep-seated tendencies can sometimes be changed through political will (witness Israel’s fertility rate). However, the default option, given a state or union’s limited resources and means, will be to work with and around these trends.

For Europeans, I suggest reacting to these mega-trends calls for: restoring our continent’s unity, rebuilding Europe’s technological sovereignty and prowess, and wholeheartedly embracing the future through family-friendly policies and renewed confidence in ourselves.

Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion (London: Penguin, 2012), p. 313.

Some will argue that Latin America has never been genuinely independent but has always been subject to neocolonial influences, notably from the United States. Power asymmetries certainly exist and these may retard economic development, especially if foreign influence promotes war or instability in a country. However, foreign influence can also be a critical condition for development if it fosters stability, trade, investment, and technology transfers. Dependency theories thus beg the question of why certain nations under U.S. influence - notably in postwar Western Europe and East Asia - have thrived economically and have in important sectors often represented fearsome competition for American companies.

I agree a rebalancing of values in favor of families and intergenerational heritage will be necessary.

FWIW, if one supports a eugenic immigration policy (primarily or at least mostly letting in those who are smart and talented rather than the dull and lazy), then it's actually perfectly logical to apply a similar policy in regards to fertility: As in, ecourage the smart and talented to breed a lot through incentives while also encouraging the dull and lazy to breed less through incentives (unless they will breed eugenically with the help of super-smart donor sperm/eggs, in which case an exception might be made for them). In fact, a eugenic policy in regards to fertility, if non-coercive, would actually be an improvement over a eugenic immigration policy because the latter often condemns the dull and lazy to lifetimes of poverty, misery, and oppression while the former simply prevents dull and lazy people from ever being born and conceived, thus ensuring that these potential people never actually suffer. As you said, a eugenic immigration policy is also very often dysgenic for the sending countries, whereas a eugenic fertility policy is more of a win-win. Even the domestic poor benefit from it because their children get larger inheritances due to them having less siblings to share and split their inheritance with.