Developing Your “Helicopter View”

You need the big picture to maximize your personal impact

Maria Linkova-Nijs, comms director for the European chemical industry association (CEFIC), recently observed on LinkedIn:

It appears that [trade] association leadership [in Brussels] do not always carefully consider upfront whether they want a comms person in a strategic advisory capacity or just somebody to “make things pretty” and only work on comms outputs without any role at the inputting stage …

It is obvious that one is likely to need a different level of seniority and competencies/expertise depending on the choice. What is sometimes less obvious to association leadership though is that if you want strategic advice, your comms advisor needs to be in a decision making room/consulted at the onset of every project and not at the very end of it to “make it pretty” or “promote” it.

For me, purely relying on a professional’s technical skills (in this case, editorial, design, video editing, or whatever), without asking them for strategic input on how to use those skills, will almost always be a missed opportunity.

The reason is simple: without the technical specialists’ strategic input, management’s requests are less likely to make sense. In the case of comms, without clear thinking on organizational needs, target audiences, most appropriate tools, and best allocation of (necessarily scarce) resources, the proposed comms actions will be suboptimal, sometimes even useless.

Management may ask their comms team to do things that don’t make sense; like try to be a mass media organization or produce a vanity video. A good comms professional will tell his or her colleagues when a proposed comms actions looks to be a waste of time and money.

If comms or other professionals are not involved in the strategic design of actions, and if the actions make no sense, naturally their motivation, buy-in, and morale are unlikely to be high. Conversely, if qualified people at all levels share relevant input into decision-making early on, one is far more likely to get the right things done.

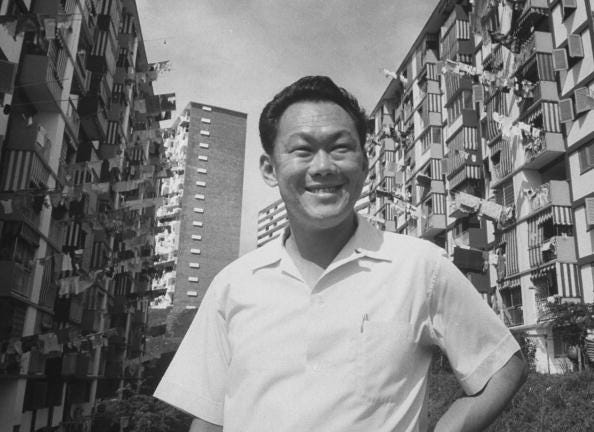

Lee Kuan Yew’s “Helicopter Vision”

To contribute strategically, one needs to be able to put one’s personal and/or technical skills in the broader context of one’s team, of one’s whole organization, and indeed the broader environment (economic, political, ecological…).

Lee Kuan Yew, the remarkably effective prime minister of Singapore, called this “helicopter quality” and considered it the prime factor in selecting for leadership potential:

I also checked with corporate leaders of [multinational corporations] how they recruited and promoted their senior people, and decided one of the best systems was that developed by Shell, the Anglo-Dutch oil company. They concentrated on what they termed a person’s “currently estimated potential.” This was determined by three qualities-a person's power of analysis, imagination, and sense of reality. Together they made up an overarching attribute Shell called “helicopter quality,” the ability to see facts or problems in a larger context and to identify and zoom in on critical details.1

The point is to be able to both zoom out to see the big picture (and thus see what actions are needed) and to zoom in on a particular situation to actually take the necessary action. Analysis, a sense of reality, and imagination work together to understand the situation and propose relevant actions.

This is not just a matter for senior management: people at every level of the organization can develop their skills so they can contribute more effectively.

Here is one way of looking at the hierarchy of skills from broadest to most particular:

Conceptual knowledge and general culture (one’s view of human life and of the world as a whole, deriving from your life experience, humanities and social sciences)

Organizational strategy (concerned with the state of one’s organization as a whole, its functioning, its strategic positions, its opportunities and weaknesses, and the best allocation of scarce resources [time, money, attention], its place in the current state of the world)

Operational skills (managing a team, shop, or a project within the organization)

Interpersonal skills (ability to communicate and collaborate effectively with others)

Personal skills (self-direction and self-management)

Technical skills (one’s narrow field of technical expertise, e.g. editorial skills, economic modeling, visual design, engineering, etc.)

Different people will naturally master different levels in this hierarchy. One person, let’s call her Sandra, is a real people-person. She has a natural knack for getting on with others and day-to-day management (strong on interpersonal or operational skills), but she lacks technical skills and has little sense of the broader picture (weak strategic skills and conceptual knowledge).

Conversely, another person, let’s call him Bob, is more comfortable with ideas and things. He has great conceptual knowledge and engineering ability, but may have difficulty applying this concretely and be useless with people. In the cases of both Sandra and Bob, their valuable skills may to some extent go to waste because of weaknesses in other areas.

No one will have all of these skills to the highest level. Hence, once must always have genuine dialogue between complementary people to see what the best action is. A good leader will have sufficient mastery at each level in the hierarchy while, especially, knowing how to draw upon and synergize the knowledge of his people.

One of the best ways of improving your helicopter vision is to ask questions and listen. Technical or junior staff can understand better how their work fits into the organization’s functioning by asking questions of managers: What is the purpose of this action? What is the underlying concern? What action would be most useful to you? What do your managers want or expect?

Similarly, managers can get a better sense of the concrete life, needs, and actions of their staff by asking questions: What obstacles do you face in your daily work? What actions do you feel are unproductive? Do you see any redundancies in our work? What productive actions could we do that we are currently ignoring? A senior manager cannot know what everyone does in detail, and no one should micromanage, but they should have some idea of how the different parts of their organization fit together so as to ensure coherence.

Developing your skills at each level

In the knowledge economy, almost everyone is a knowledge worker to some extent and, thereby, an executive who can contribute to identifying the most relevant actions for themselves and the organization. For this, you need at least adequate skills at each level (assuming you do not want a completely narrow role, e.g. just doing what you’re told without asking yourself whether what you’re told is relevant).

You can identify your weak spots and work on them, whether by taking a training course, reading a book on professional development or leadership, or consciously observing and taking inspiration from people who fulfill these roles well.

Technical skills are your practical specialized skills in a given area, such as reporting, visual design, coding, or econometrics. Such skills are often key to getting your foot in the door of an organization.2

Many graduates of the humanities or social sciences may, wrongly, think themselves of low professional value because of lack of technical skills. In fact, as one rises in leadership, technical skills typically decline in salience.

A good leader will have a sense of the possibilities and limitations of current technologies and techniques, but he or she will increasingly rely on their staff for detailed knowledge and especially practical implementation. Anyway, in our day and age, specific technical skills can rapidly become obsolete with changes in technology. It is crucial to be able to adapt.

Personal skills refer to your ability to manage and direct yourself. It notably includes knowledge of yourself (of your values, tastes, preferences, and limitations). It also includes specific abilities, such as the capacity to set priorities for yourself, to regularly plan important actions, and to manage one’s emotions, especially in the face inevitable obstacles and setbacks.

The constant cultivation and development of your character is your life’s mission and will basically determine your capacity to have a positive impact throughout your life, amidst all the inherent uncertainties.

Interpersonal skills are equally essential to just about everyone. These refer to your ability to communicate and collaborate with others. This includes, among other things, your ability to listen to and understand others, to express your viewpoints with courage and consideration for others, to find mutually-beneficial understandings and agreements, and to spread good feeling and understanding among your partners and team.

Without interpersonal skills, your impact will be limited to the capacities of one person: you. That might—perhaps—suit the lonely artist or genius, but as a rule: what a waste! Through strong interpersonal skills you can multiply your capacities through collaboration with others.

With strong interpersonal skills, you can also harmonize yourself with an organization or team, thus maximizing your impact by taking the most relevant particular action in view of the whole, as well as by contributing to orienting the organization’s work.

Operational skills are especially relevant for middle management. These include all the skills relevant to, say, managing an event, a team, a long-term project, or a shop. In terms of day-to-day management, this includes ensuring the right people are in the right positions with the right knowledge, careful monitoring to ensure key conditions are being met, and effective prioritization. One is like the conductor of an orchestra or, rightly understood, a juggler of challenges.

A good operational manager will reduce unproductive stress, take setbacks in stride, create a culture where problems are systematically identified, openly discussed, and rapidly reacted to, and radiate positive emotional energies.

For developing operational skills, there seems to be no substitute for experience. One has to throw oneself into the uncertainty of managing a project—particularly daunting precisely when one has no experience—in the calm knowledge that you don’t know what the results will be.

Consider film direction: how much uncertainty is involved with respect to the actors’ personalities and chemistry, the negotiations with the studio, technical difficulties, the gap between vision and execution, or even having to deal with bad weather and limited time! Even the greatest film directors will, by human imperfections and the vagaries of fortune, occasionally make bad films (unless you’re Stanley Kubrick).

Organizational strategy concerns the highest strategic skills relevant to your particular organization. This includes having an in-depth understanding of your organization’s current state, systems, and capacities, but also of how your organization fits into the broader (business or political) environment, including keeping up with current affairs and the state of the world.

This is not knowledge for its own sake, but knowledge which must be concentrated to make strategic decisions with other key players in the organization. Thus, organizational strategy also requires the ability to stoke frank debate and solicit insights from your key players, and the ability to create consensus and unity of purpose when the decision is taken.

Organizational strategy includes: separating the essential from the distractions; identifying priorities and goals for the coming years; identifying the key decision points and alternatives; and deciding on the allocation of (necessarily scarce) organizational and financial resources.

For political organizations, relevant questions may include: what political positions do we want to uphold and become known for? What other organizations and stakeholders do we want to influence or strengthen our relationships with? How should we be internally organized for maximal effectiveness? How should we invest our limited political capital and financial resources?

There is much more I could say on organizational strategy but I think it amply merits a stand-alone post. Suffice to say that strong strategic organizational thinking will tell you whether your day-to-day actions make sense at all. Excellent road-building efforts are useless if you’re building a road to nowhere. On the contrary, if you have identified a meaningful way forward, and if all are convinced because you have drawn from your people’s collective intelligence and wisdom, teams can work with confidence and enthusiasm.

Conceptual knowledge or general culture feed into your general vision of the world and of human life. The greatest leaders have often emphasized the importance of general culture and a rich understanding of human nature, achieved through reflection on one’s life experience and a deep engagement with the social sciences and humanities.

Your personal and strategic action will necessarily be informed by your understanding of the general nature of existence, of human nature, and of what makes for a meaningful life. General culture and learning from past human experience (whether in a great politician’s memoirs, an ethical handbook, a Jane Austen novel…) will prepare you for the different phases of life and for the inevitable setbacks and drudgery. Wisdom teaches humility—an awareness of the very real limitations and principles that govern human life—without ceding to discouragement, which is useless.

Through your life experience and your engagement with philosophy, religion, and/or classic works, you will develop convictions and a life philosophy. A person without such an engagement may find, at the end of his life, that he or she pursued wrong or trivial things (mere money, for example) but that these, even if secured successfully, did not bring them meaning or happiness. General culture may also ward you against pursuits that are unwise, arrogant, or totally impossible.3

Winston Churchill advised a young man who asked what was the best education for engaging in politics: “Study history, study history. In history lies all the secrets of statecraft.”

Henry Kissinger, in his remarkable recent book Leadership, stresses the importance of both history and philosophy as fundamental sources of inspiration. He writes:

The technician’s education tends to be pre-professional and quantitative; the activist’s, hyper-specialized and politicized. Neither offers much history or philosophy—the traditional wellsprings of the statesman’s imagination.4

Kissinger also recommends a renewed interest in “politics, human geography, modern languages, … economic thought, literature and even, perhaps, classical antiquity.”5 I would add, given the insights of modern evolutionary science into human nature, the relevance of evolutionary psychology and behavioral genetics for better understanding human beings.

In practical terms, general culture will culminate in subtle convictions, a realistic appreciation of human life, and a healthy sense of both existential limits and the constant possibility of meaningful action. The more meaning you can infuse into your daily life, the more you will inspire others: nothing convinces like conviction! The young Charles de Gaulle wrote: “The man of character confers nobility upon action; without this it is the slave’s thankless task, with it it becomes the hero’s divine game.”6

Recap: develop your helicopter vision

To make the most of your potential, you must develop your helicopter vision: your ability to both zoom out to see the big picture and to zoom in on a particular situation. Together, these will enable you to propose and execute the most relevant and impactful actions for both yourself and your organization. In this way, your particular skills will not be wasted on useless actions and your knowledge will inform strategy.

Helicopter vision implies skills at every level: technical, personal, interpersonal, operational, organizational (strategy), and in terms of general culture. You are not expected to be a Renaissance man. However, you need to have adequate skills at each level and, especially, an ability to tap into the knowledge and skills of people in your organization, at every level, through open and constructive dialogue. In a complementary team, each member’s areas of weakness become irrelevant.

As Peter Drucker said: “The effective executive gets the right things done.” In a knowledge economy, we all to some extent become executives. To be effective, you need to identify what is the best action to be taken. If your team has identified together what needs doing and you have genuine consensus regarding the way forward, work takes on a new character, as you move forward together with conviction and confidence.

Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: Singapore and the Asian Economic Boom (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), p. 668.

Sometimes one can gain prominence by a mixture of technical and conceptual expertise. As a junior military officer in the 1930s, Charles de Gaulle made a name for himself through his knowledge and advocacy of tank warfare, then a cutting-edge technology. Unfortunately, the French leadership clung to an essentially defensive and static conception of war, while the Germans embraced the concentrated use of armor, with brilliant results during the blitzkrieg campaigns.

In the 1950s, Henry Kissinger was an academic who had written on the philosophy of history (his 400-page [sic!] bachelor’s thesis is entitled “The Meaning of History: Reflections on Spengler, Toynbee and Kant”) and on peacemaking in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars. You might think such a man would be utterly impractical outside of academia. Yet Kissinger then worked on nuclear strategy—again a cutting-edge technology of political relevance—and came to the attention of Nelson Rockefeller, serving as a foreign policy advisor to him and then to Richard Nixon. Kissinger would go on to become one of the United States’ most thoughtful and effective top foreign-policy officials.

I could provide innumerable examples of this in politics. How many times did a revolutionary seek to change everything all at once, only to do tremendous harm and leave his country under an even worse tyranny!

Henry Kissinger, Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy (New York: Penguin, 2022), p. 516.

Kissinger is quite negative in his assessment of the current state of university education and the impact of social media on capacity for deep thinking:

As we have seen, leaders with world-historical impact have benefited from a rigorous and humanistic education. Such an education begins in a formal setting and continues for a lifetime through reading and discussion with others. That initial step is rarely taken today—few universities offer an education in statecraft either explicitly or implicitly—and the lifelong effort is made more difficult as changes in technology erode deep literacy. Thus, for meritocracy to be reinvigorated, humanistic education would need to regain its significance, embracing such subjects as philosophy, politics, human geography, modern languages, history, economic thought, literature and even, perhaps, classical antiquity, the study of which was long the nursery of statesmen. (Kissinger, Leadership, p. 520)

Charles de Gaulle, The Edge of the Sword (1932).