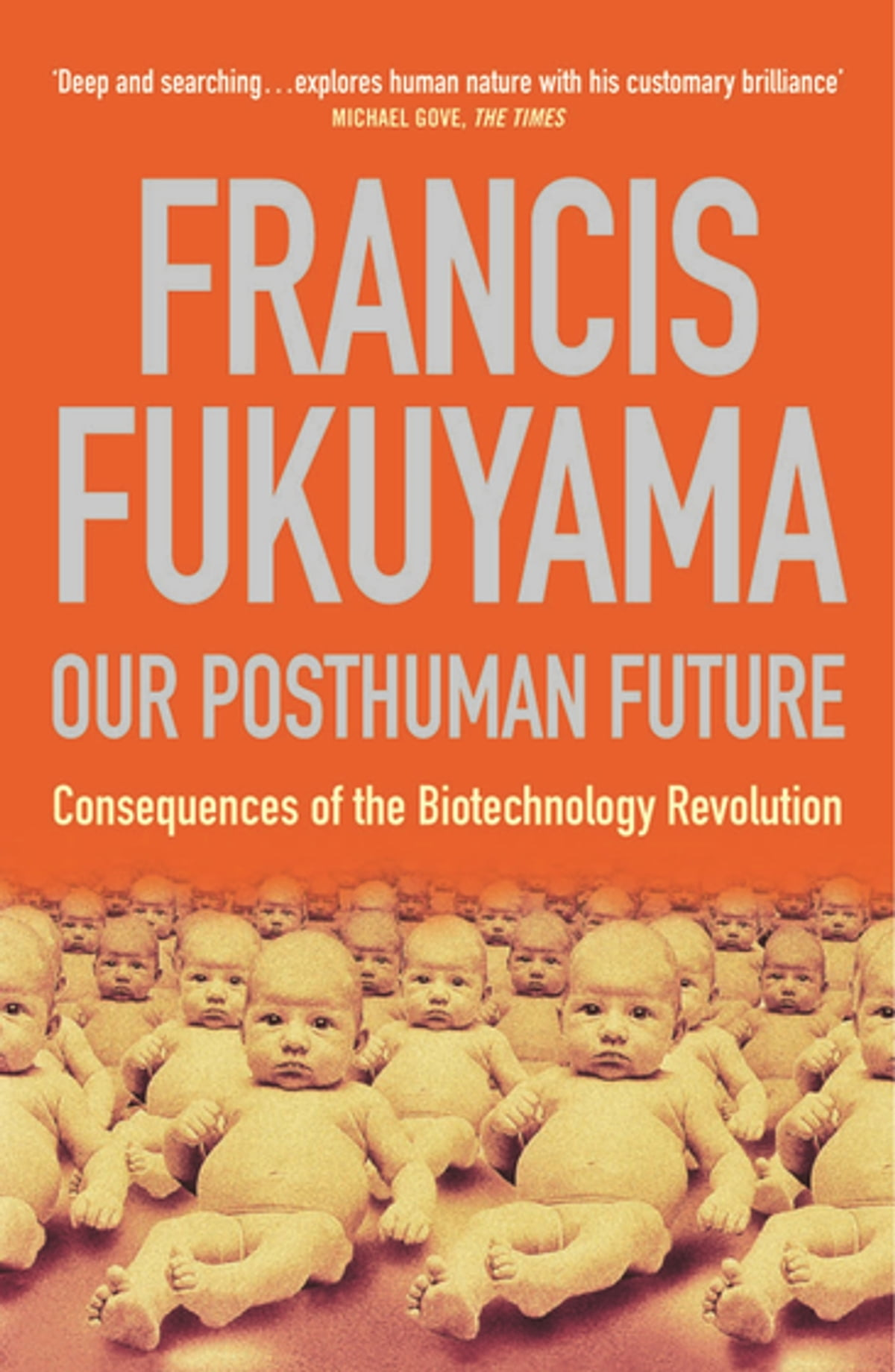

Fukuyama, Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002)

I am sometimes asked what biology could possibly have to do with politics. For the answer, look no further than this book by Francis Fukuyama. Yes, that Francis Fukuyama, the end-of-history person. Written way back in 2002, Fukuyama examines how we should use or restrict such emerging human biotechnologies. It’s striking how well the book has aged as he looks at trends that have since become well-established: the use of mind-altering prescription drugs, aging societies, and novel biotechnologies such as largescale genomics and gene editing.

Fukuyama strikes a cautionary note by looking at the impact of already-existing biotechnologies. He points to the explosion in use of Ritalin and Prozac in the United States. Tens of millions of Americans use these drugs, respectively, to treat ADHD and improve concentration, and to lift self-esteem and treat depression. Thus biotechnology (specifically neuropharmacology) is already being used to narrow the normal gamut of human emotions. Fukuyama identifies powerful pressures pathologizing more and more mental states and thus “requiring” medical treatment:

The first is the desire on the part of ordinary people to medicalize as much of their behavior as possible and thereby reduce their responsibility for their own actions. The second is the pressure of powerful economic interests to assist in this process. These interests include social service providers such as teachers and doctors, who will always prefer biological shortcuts to complex behavioral interventions, as well as the pharmaceutical companies that produce the drugs. The third trend, which flows from the attempt to medicalize everything, is the tendency to expand the therapeutic realm to cover an ever larger number of conditions. It will always be possible to get a doctor somewhere to agree that someone's unpleasant or distressing situation constitutes a pathology, and it is only a matter of time before the larger community comes to regard such a condition as a legal disability subject to compensatory public intervention. (p. 53)

The second disturbing trend Fukuyama identifies is the tendency to prolong human lives indefinitely, often to the detriment of the young and with little regard for declining quality of life as we age. He fears the emergence of gerontocratic societies dominated by the old and considers that rising political correctness - “agism” - will make frank and rational discussion this (and many other) issues impossible.

If there is a common running theme here, it is that biotechnology will increasingly be (ab)used in service of seemingly unquenchable human desires - for comfort, convenience, health, status… - and thus lead to negative collective outcomes.

From human nature to politics

From the starting point of biotechnology, Fukuyama actually engages in a far broader reflection on human nature, what the life sciences tell us about human nature (including discussion of intelligence, twin studies, and sex differences, as well as a fair summaries of the Bell Curve affair and the history of Darwinian social science1), and the implications for politics. In a nutshell: Aristotle meets Darwin. In my view, this approach is basically correct and, whatever the weaknesses in this book, Fukuyama should be lauded for making the attempt. Κατά φυσίν!

I am continually surprised at how few bioethicists and political philosophers make the attempt to inform theories in knowledge of biological human nature. It is disputed whether one can derive ethical imperatives from empirical study of nature (the famous is-ought problem and disputed naturalistic fallacy). However, at the least, your ethical theory needs to be congruent with what is known about human nature.

False ideas about human nature often have terrible consequences. Communism’s failure was grounded in unrealistic expectations of human virtue and impossible egalitarian ambitions. Similarly, Nazism failed in no small part because of exaggerated claims of German national-ethnic superiority (it turned out the scorned Slavs Hitler had planned to turn into helots could be excellent organized fighters). Where the laws of (human) nature are concerned, Cecil DeMille’s famous saying comes to mind: “It is impossible for us to break the law. We can only break ourselves against the law.”

More recently, gender theory has claimed that human nature does not feature any innate link between biological sex and gender identity/behavior. Fukuyama cites the tragic case of David Reimer. As an infant, Reimer lost his penis during a botched circumcision. An influential gender theorist, John Money, convinced the parents that, because gender was entirely learned, the boy should be castrated and raised as a girl (he was renamed Brenda). Despite losing his testicles and being forced to wear frilly dresses and take female hormones, “Brenda” refused to identify as a girl. While he later married, Reimer struggled with depression and marital troubles, committing suicide in 2002 at the age of 38. Fukuyama writes of this horrifying case:

What is noteworthy about this story, however, is that Money could assert for almost fifteen years in scientific papers that he had succeeded in changing Brenda’s sexual identity to that of a girl, when exactly the opposite was the case. Money was widely celebrated for his research. His fraudulent results were hailed by feminist Kate Millet in her book Sexual Politics, by Time magazine, and by The New York Times and were incorporated into numerous textbooks, including one in which they were cited as proving that “children can easily be raised as a member of the opposite sex” and that what few inborn sex differences might exist in humans “are not clear-cut and can be overridden by cultural learning.”2 (p. 95)

An empirical notion of human dignity

Fukuyama is an underrated and overexposed writer. Going viral avant la lettre in 1989 will do that to you. But whatever one thinks of their conclusions, Fukuyama’s books provide a thoughtful prolonged intellectual argument and a highly informative tour of various data sources and conflicting points of view. The latter includes both the views of contemporary scholars of various persuasions and the insights of great philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, and Nietzsche. Hence, Fukuyama is able to give perspective to the controversies of the day and not be wholly possessed by current intellectual fashions. He can also be a ruthless writer, pouring scorn on political correctness, Rawlsian liberals, and utilitarian bioethicists.

Our Posthuman Future provides a highly defensible, moderately inegalitarian case for human dignity grounded in the confluence of human faculties:

What is Factor X [underpinning human dignity]? That is, Factor X cannot be reduced to the possession of moral choice, or reason, or language, or sociability, or sentience, or emotions, or consciousness, or any other quality that has been put forth as a ground for human dignity. It is all of these qualities coming together in a human whole that make up Factor X. (p. 171)

Significantly, these traits are not equally distributed over our lifetimes and across the population. Thus, Fukuyama notes, children (relatively lacking in reason) do not acquire their full rights until adulthood, Alzheimer’s patients may legally lose the right to make financial decisions, and criminals (presumably sociopathic) can also be deprived of certain rights.

There is a clear tension here with the official line of Fukuyama’s liberal-democratic program. He writes early on: “The political equality enshrined in the [American] Declaration of Independence rests on the empirical fact of natural human equality” (p. 9).3 Yet, by his own account, such equality does not exist. Fukuyama makes however a reasonable case for liberal-democracy and “not being too hierarchical in the assignment of political rights” (p. 175) on pragmatic and prudential grounds: claims of superiority are difficult to assess and are always self-interested.

What emerges is that Fukuyama’s support for liberal-democracy seems to be grounded in the civic-republican tradition (e.g., Aristotle and Machiavelli) and not the Anglo-liberal tradition. Indeed, Fukuyama has little patience for “dogmatic” Anglo-liberal claims of disembodied and absolute human equality, dignity, and autonomy: “The idea of the equality of human dignity, deracinated from its Christian or Kantian origins, is held as a matter of religious dogma by the most materialist of natural scientists” (p. 156).

An abrupt conclusion: against enhancement

In his conclusion, Fukuyama abruptly pivots with a case for national and international regulation of biotechnologies to prevent harmful use. This is so obviously necessary as to seem a trivial point, although maybe it was not so obvious in 2002.

More puzzlingly, Fukuyama’s conclusion argues for a total ban on all forms of genetic enhancement, on the grounds that tampering with human nature could make liberal democracy untenable by creating caste-like biological inequalities, making humans lose their shared range of emotions, and ultimately splintering the human race.

While these risks are worth guarding against, the total aspect of the ban is strangely under-argued, especially as Fukuyama had previously broached forms of enhancement (such as subsidizing genetic enhancement for the less privileged) that would be eminently compatible with liberal democracy (p. 81). And what of interventions that would enhance the traits Fukuyama claims underpin humaneness, such as moral choice, reason, sociability, and certain emotions? It is also unclear what would constitute an “enhancement” as against a therapeutic intervention or mere selection (e.g., do gene editing to prevent mental disability or embryo selection for naturally-occurring high-IQ constitute “enhancement”?).

With that caveat, I encourage people to read Our Posthuman Future as a worthy attempt to ground politics in human nature. It is, unfortunately, not a crowded field.4 As useful contrasts and complements to Fukuyama’s case, I recommend Anomaly and Jones on cognitive enhancement and Anomaly and Faria on the long-term evolutionary viability of liberalism.

You can can get idea of the depth and dialectical ambiguity of Fukuyama’s writing in the following passage:

Americans more than most peoples have tended to conflate rights and interests. By transforming every individual desire into a right unconstrained by community interests, one increases the inflexibility of political discourse. The debates in the United States over pornography and gun control would appear much less Manichean if we spoke of the interests of pornographers rather than their fundamental First Amendment right to free speech, or the needs of owners of assault weapons rather than their sacred Second Amendment right to bear arms.

So why not abandon what legal theorist Mary Ann Glendon labels rights talk altogether? The reason we cannot do so, as either a theoretical or practical matter, is that the language of rights has become, in the modem world, the only shared and widely intelligible vocabulary we have for talking about ultimate human goods or ends, and in particular, those collective goods or ends that are the stuff of politics. Classical political philosophers like Plato and Aristotle did not use the language of rights – they spoke of the human good and human happiness, and the virtues and duties that were required to achieve them. The modern use of the term rights is more impoverished, because it does not encompass the range of higher human ends envisioned by the classical philosophers. But it is also more democratic, universal, and easily grasped. The great struggles over rights since the American and French revolutions are testimony to the political salience of this concept. The word right implies moral judgment (as in, “What is the right thing to do?”) and is our principal gateway into a discussion. (p. 108)

While Fukuyama rebuts the attacks of Richard Lewontin and Stephen J. Gould against Darwinian social science, he endorses Franz Boas. The validity of Boas’ most famous study, claiming to show environmental determination of skull shape (cited by Fukuyama), has since also been contested.

It is noteworthy that Fukuyama wrote and published the book before learning of David Reimer’s suicide.

This tension goes back at least as far as Thomas Jefferson himself, who while famously proclaiming that “all men are created equal,” not only owned black slaves but also privately endorsed the idea of a merit-based “natural aristocracy.”

There are great books on human nature from an evolutionary perspective. I think of Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate on left-wing attacks on Darwinian social science and Robert Plomin’s Blueprint on genetics, though both are somewhat lacking in the political dimension. Kevin MacDonald’s A People That Shall Dwell Alone comes close insofar as it looks at the impact of culture on group evolutionary success, but arguably it is more historical than generally political. Jonathan Anomaly’s Creating Future People explores what would constitute desirable enhancements as against harmful interventions, while Filipe Nobre Faria’s The Evolutionary Limits of Liberalism, as the name suggests, questions the long-term biological viability of liberal-democracy.