Is France cooked?

The Prime Minister warns boomer pensions are bankrupting the country

A substantial part of my online writing over the past decade-and-a-half has been dedicated to defending France. As a French-American, I always took umbrage when reading what I felt to be unfair analyses of France in English-speaking media.

I would often write about how, contra the criticisms of magazines like The Economist, the French economy’s performance was in line with other developed countries. Despite France’s high taxes and regulated labor market, its productivity was on a par with the U.S. and its public debt was comparable to the UK. While the French model also had disadvantages, not least chronic 8-10% unemployment, I felt French voters had a right to choose a social model which also offered real benefits: a high degree of economic equality, social security, work-life balance, and high-quality and accessible healthcare.

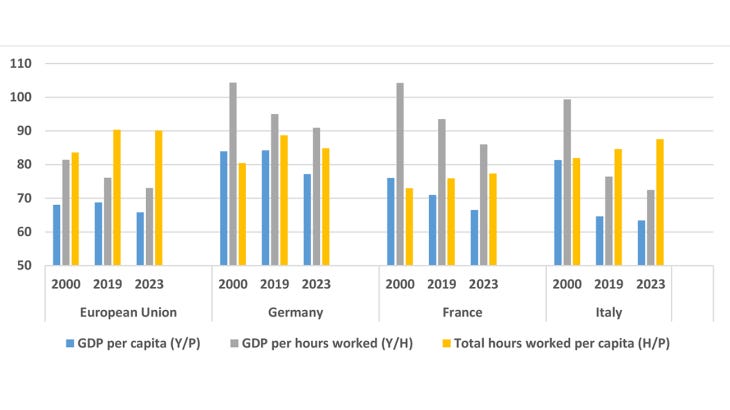

It now seems to me that the French model can no longer be defended in this way. For one, French (and broader European) productivity has collapsed relative to the U.S. since 2000.

When I came of age circa 2005, it arguably wasn’t obvious that the U.S. economy would be decisively superior to the EU’s. The Europeans had some significant factors in their favor, including eastern enlargement (which has contributed to EU growth through labor migration and the integration of fast-growing emerging economies), an apparently functional monetary union, and the ongoing project of tearing down barriers to services trade within the EU single market. Not to mention the fact that the U.S. was wasting untold trillions of dollars in failing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as an extraordinarily costly healthcare system.

However, the EU-U.S. economic gap has since become too severe to ignore and, given ongoing demographic and policy factors, will likely widen still. As former European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi wrote in his famous report on competitiveness: “Across different metrics, a wide gap in GDP has opened up between the EU and the US, driven mainly by a more pronounced slowdown in productivity growth in Europe.”

Factors slowing growth and innovation in the EU include a flawed monetary union (depressing growth in southern Europe especially), a fragmented single market for many sectors, an older population, a lower economic contribution of immigrants relative to the U.S. (because more unskilled, more non-working, and welfare being more accessible), costly energy policies, and an often precautionary regulatory culture. This adds up to a far less favorable climate for investment (less venture capital, higher taxes, and costly labor laws if a failing company ever has to shed employees). As a result, Europeans have less money to invest and far lower upshot for investing in the high-risk, high-reward ventures that will define the economy of tomorrow.1

Whatever the causes, the U.S. has many thriving high-valuation new companies (unicorns), and the EU does not. The global share of EU (and Japanese) private R&D has also declined significantly in recent decades, while the U.S. has consistently contributed over 40% of global private R&D investment. The trends are also evident in particular sectors like pharmaceuticals and biotech. The U.S. economy is now bigger than the rest of the G7—Japan, Germany, the UK, France, Italy, and Canada—combined. (For more on the EU’s economic travails and potential solutions, I recommend following the economist Luis Garicano.)

So much for Europe. But this post is about France. What is the specifically French problem? Besides relative economic decline, France is now on the road to fiscal Italianization.

People have criticized French fiscal profligacy for decades. Until relatively recently, French indebtedness was in fact broadly in line with other developed countries. But under President Emmanuel Macron (in office since 2017), France’s fiscal situation has steadily worsened and is set to continue to deteriorate over the next years.

The European Commission forecasts a public deficit of almost 6% of GDP for France this year and next, with debt rising to 118.4% of GDP by 2026, compared to Italy’s 138.2% and Germany’s 64.7%. The UK’s debt, which used to be comparable to France, is forecast to reach 103.8%.

Rising debt is normal in times of crisis. But there is no crisis today. This is just run-of-the-mill peacetime fiscal decay.

So what is causing the rise in French debt? Over the 2018-2023 period, the debt has increased by 839 billion euros. Pensions are the main culprit, being responsible for 52% of the total increased spending. Crisis spending due to COVID, inflation, and Ukraine accounts for 26% and some tax cuts in the early part of Macron’s first term for 22%.

Pensions make up over a quarter of French public spending (and bear in mind public spending makes up a staggering 57% of GDP in France!):

Why is French pension spending so high? The cause is only partly demographic, the subject dear to this blog, in the form of population aging. After all, population aging is happening across the developed world and if anything thanks to immigration and comparatively high fertility France isn’t aging as fast as most of Europe.

Pension spending is partly made higher by the low retirement age of 62 which, under Macron’s controversial 2023 pension reform, is being gradually raised to 64 by 2030.

But the main issue is how pensions are calculated, which only loosely corresponds to how much a person paid into the system. It follows a formula which varies according to one’s employment. For private sector workers this is equal to half of one’s gross average income over the 25 best-paid years of one’s career, while civil servants receive a much better deal: 75% of their salary during their last 6 months of work.

The upshot is one can, over one’s retirement, receive much more than one actually paid in social contributions. Indeed, it is estimated that boomers will on average receive twice as much in pensions than they put into the system.

Pension reform has been politically toxic in France for decades. The country has long had gerontocratic tendencies with high-turnout elderly voters being particularly feared by politicians.

Today, any pension reform, and really any attempt at cutting spending or further raising taxes to reduce the deficit, is compromised by the fact that the French political system is gridlocked. The government has no majority. About a third of French vote for pro-welfare nationalists, a third for pro-welfare leftists, and a third for moderate centrists (who have no particular appetite to cut spending but don’t want the system to collapse).

Not only is France’s pension system chronically bankrupt but the two main opposition forces, the nationalist RN and the leftist LFI, both want to reverse Macron’s timid pension reform of 2023 and lower the retirement age back to 62. So fiscally, you’re looking at things being bad under the gridlocked centrists or even worse under either brand of populists.

French Prime Minister François Bayrou, a centrist, recently threw up his hands by turning the vote on the country’s next budget in Parliament, which includes various measures to reduce the deficit by 44 billion euros, into a vote of confidence. This means his government will almost certainly fall next month as nationalist and leftist MPs vote down the budget.

Interestingly, Prime Minister Bayrou has decided to flame out by attacking boomers and the French pension system as a whole. He said a few days ago:

If we create chaos, who will be the victims? The first will be French young people who will have to pay for this debt their whole lives … all this for the comfort of certain political parties and the comfort of boomers.

Though the criticism of boomers caused controversy, Bayrou then doubled down, telling the MEDEF business lobby (French equivalent of the Chamber of Commerce):

We are in the process of accepting that the youngest be reduced to slavery by forcing them for decades to repay the loans lightly decided upon by previous generations.

He then broadened the critique to the French healthcare system, saying: “We are making our children pay for our medical bills!” Bayrou argues that rising healthcare and pensions spending is a crippling burden for French workers due to social charges and for future generations of young people.

While boomers’ overblown pensions are bankrupting France, in one sense boomers themselves are not to blame and certainly do not deserve all the blame. After all, as lovers of stability they are the most stalwart supporters of the centrist parties.

In fact, French young people are also substantially to blame. Macron’s tepid 2023 pension reform led to massive social unrest in which young people played a major role. Over 80% of French young people (aged below 35) opposed the reform. French young people seem to think public pensions’ sustainability is merely a matter of political will and one’s preferred conception of social justice.

Presumably the fall of the government next month will be followed by elections (again). This would lead either to a left-wing government, a nationalist government (43% of French voters want an RN victory), or another gridlocked Parliament (I highly doubt the centrists can eke out a majority).

If the left or nationalists win, they will face the same grim economic conundrum, but with even more unrealistic expectations.

An eventual left-wing government could crumple if its economic policies prove ineffective and non-credible, as happened to Syriza in Greece, M5S in Italy, or Podemos in Spain. Far-left firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon made a very macho appearance in the media recently during which he threatened to not repay creditors—so financial markets had better behave. This would be more credible if France did not have a 3.7% primary deficit (the deficit minus the cost of servicing existing debt). Defaulting on the debt would require massive and immediate budgets cuts and/or tax increases, not even counting all the associated economic disruption.

An eventual nationalist government would have a bit more room for maneuver, insofar as they could try to pivot the focus to immigration issues. Nationalists want to make savings by reducing France’s contribution to the EU and depriving immigrants of access to welfare and free healthcare. There is also a growing body of evidence from countries like Denmark, the Netherlands (p. 19), and Finland (p. 7) finding that on average non-Western immigration to Europe represents a significant net fiscal burden to host countries. Nonetheless, as Elon Musk found out in the U.S., cracking down on immigration and shutting down progressive government projects and perceived “waste, fraud, and abuse” are unlikely to eliminate deficit spending unless ballooning entitlements, namely pensions and healthcare spending, are reduced. But populists are unsurprisingly loath to do something so unpopular with voters.

Either a nationalist or a leftist government could end up falling into a fiscal crisis should markets decide lending to the French state is too risky. Much will depend on the attitude of the ECB. A fiscal crisis’ consequences would be unpredictable but would presumably lead to discrediting the government and then a forced pivot to austerity and neoliberal reforms. (The latter last happened in France in 1983 with the tournant de la rigueur, ending a Socialist government’s two-year experiment in hyper-Keynesian economics.)

Perhaps the most likely outcome is further gridlock. Then the weak government would be stuck with continued accumulation of debt for the years to come. Pensions and much other spending rises automatically with inflation, making them particular difficult to reduce in real terms. In a few years, France’s debt could reach Italian levels and French politics too largely would become a constant struggle of trying to eke out a little extra growth and cut chronic deficits just to keep the ship afloat.

This is a sad destiny for France. Since President Charles de Gaulle in the 1960s, the country has been geopolitically interesting as just about the only European nation which sought a vigorous foreign policy independent of the United States. These French ambitions were long seen as quaint by other Europeans—perhaps less so now in the age of President Donald Trump, who is both exceptionally unpredictable and expects Europeans to finally start paying for their own security. What a shame that, at this moment, France’s financial capacity to sustain an independent world role is deteriorating so fast.

Unappetizing prospects all around!

According to the Draghi Report: “In 2021, EU companies spent about half as much on R&I as share of GDP as US companies—around EUR 270 billion—a gap driven by much higher investment rates in the US tech sector. … Once companies reach the growth stage, they encounter regulatory and jurisdictional hurdles that prevent them from scaling-up into mature, profitable companies in Europe. As a result, many innovative companies end up seeking out financing from US venture capitalists (VCs) and see expanding in the large US market as a more rewarding option than tackling fragmented EU markets.”

Agreed that France desperately needs to lower its enormous debt, but austerity measures are somehow political suicide. I wrote something similar over here:

https://kainesianmacro.substack.com/p/why-france-is-looking-a-bit-italian

As a French citizen, I can unfortunately only agree with your analysis. The situation is particularly exasperating given the distortion between fiscal reality and the media discourse, which at best outrageously downplays the problems of our country, and at worst actively contributes to denying them.

It must be said that announcing on the media the dire need for reforms is quite frequent but putting forward even the beginnings of concrete proposals is far less common. The population is not ready to accept unpopular yet necessary measures. The fact that one in five working people is employed in the public sector, nearly 17 million French citizens are retired—almost one-third of the population—and, as stated in your article, about 8% are unemployed (though without some accounting tricks, the figure is undoubtedly higher) makes the issue of fiscal reforms deeply explosive.

While anxiety is palpable—despite the complacency and forced optimism of both far-right and far-left movements—the population is, overall, resigned, much like in your illustration for the article: ready to boil.