James Watson on “Gattaca,” Genetic Enhancement, and Love

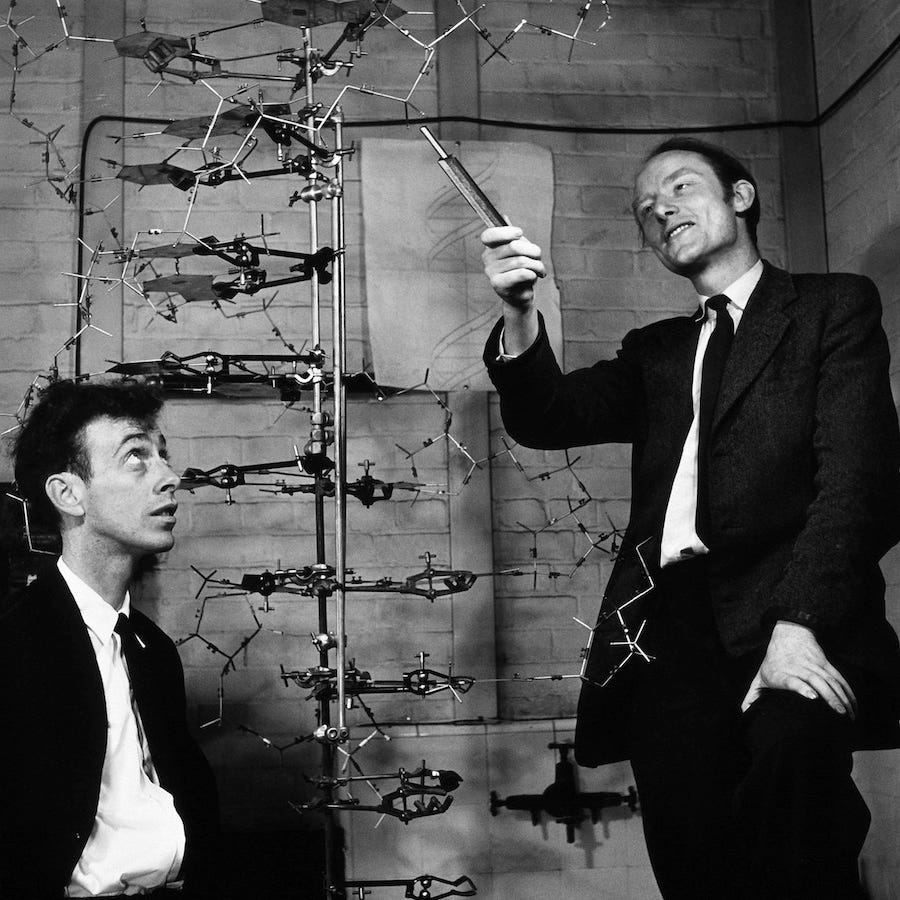

In memoriam of the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA

James Watson, the co-discoverer with Francis Crick of the double-helix structure of DNA, recently died at age 97. The Nobel Prize winner was no stranger to controversy. In his 2003 book DNA: The Secret to Life, Watson discusses how his advocacy for reprogenetic choice led to controversy in German media. He makes an earnest case for looking genetic realities in the face and using genetic enhancement motivated by love for future generations.

Below are some extracts from the book’s conclusion, entitled “Our Genes and Our Future.”1 Watson’s thoughts on genetic enhancement can profitably compared to those of CRISPR co-developer and fellow Nobel Prize-winner Jennifer Doudna. My bolding.

Only with the discovery of the double helix and the ensuing genetic revolution have we had grounds for thinking that the powers held traditionally to be the exclusive property of the gods might one day be ours. Life, we now know, is nothing but a vast array of coordinated chemical reactions. The “secret” to that coordination is the breathtakingly complex set of instructions inscribed, again chemically, in our DNA.

But we still have a long way to go on our journey toward a full understanding of how DNA does its work. In the study of human consciousness, for example, our knowledge is so rudimentary that arguments incorporating some element of vitalism [the idea that organisms are defined by non-materialist forces or qualities] persist, even as these notions have been debunked elsewhere. Nevertheless, both our understanding of life and our demonstrated ability to manipulate it are facts of our culture. Not surprisingly, then, Mary Shelley [author of Frankenstein] has many would-be successors: artists and scientists alike have been keen to explore the ramifications of our newfound genetic knowledge.

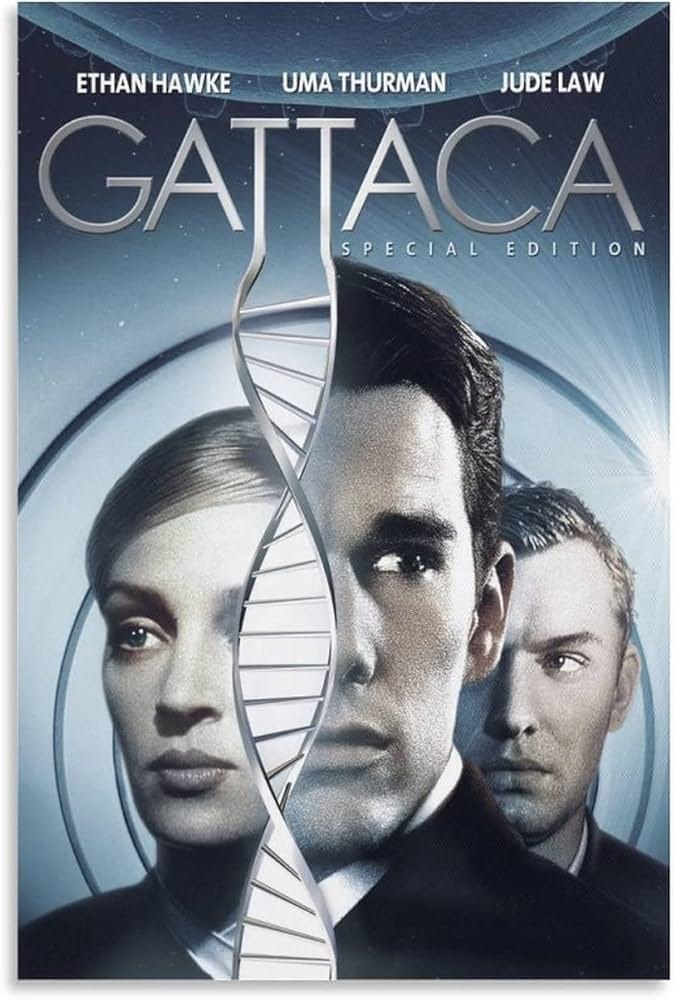

Many of these efforts are shallow and betray their creators’ ignorance of what is and is not biologically feasible. But one in particular stands out in my mind as raising important questions, and doing so in a stylish and compelling way. Andrew Niccols’s 1997 film Gattaca carries to the present limits of our imagination the implications of a society obsessed with genetic perfection. In a future world two types of humans exist—a genetically enhanced ruling class and an underclass that lives with the imperfect genetic endowments of today’s humans. Supersensitive DNA analyses ensure that the plum jobs go to the genetic elite while “in-valids” are discriminated against at every turn. Gattaca’s hero is the “in-valid” Vincent (Ethan Hawke), conceived in the heat of reckless passion by a couple in the back of a car. Vincent’s younger brother, Anton, is later properly engineered in the laboratory and so endowed with all the finest genetic attributes. As the two grow up, Vincent is reminded of his own inferiority every time he tries, fruitlessly, to best his little brother in swim races. Genetic discrimination eventually forces Vincent to accept a menial job as a porter with the Gattaca Corporation. …

Few, if any, of us would wish to imagine our descendants living under the sort of genetic tyranny suggested by Gattaca. Setting aside the question of whether the scenario foreseen is technologically feasible, we must address the central issue raised by the film: Does DNA knowledge make a genetic caste system inevitable? A world of congenital haves and have-nots? The most pessimistic commentators foresee an even worse scenario: Might we one day go so far as to breed a race of clones, condemned to servile lives mandated by their DNA? Rather than strive to fortify the weak, would we aim to make the descendants of the strong ever stronger? Most fundamentally, should we manipulate human genes at all? The answers to these questions depend very much on our views of human nature.

Today much of the public paranoia surrounding the dangers of human genetic manipulation is inspired by a legitimate recognition of our selfish side—that aspect of our nature that evolution has hardwired to promote our own survival, if necessary at the expense of others. Critics envision a world in which genetic knowledge would be used solely to widen the gap between the privileged (those best positioned to press genetics into their own service) and the downtrodden (those whom genetics can only put at greater disadvantage). But such a view recognizes only one side of our humanity. …

Disposed though we might be to competition, humans are also profoundly social. Compassion for others in need or distress is as much a genetic element of our nature as the tendency to smile when we’re happy. …

Even those who accept that the urge to improve the lot of others is part of human nature disagree on the best way to go about it. It is a perennial subject of social and political debate. The prevailing orthodoxy holds that the best way we can help our fellow citizens is by addressing problems with their nurture. Underfed, unloved, and uneducated human beings have diminished potential to lead productive lives. But as we have seen, nurture, while greatly influential, has its limits, which reveal themselves most dramatically in cases of profound genetic disadvantage. Even with the most perfectly devised nutrition and schooling, boys with severe fragile X disease will still never be able to take care of themselves. Nor will all the extra tutoring in the world ever grant naturally slow learners a chance to get to the head of the class. If, therefore, we are serious about improving education, we cannot in good conscience ultimately limit ourselves to seeking remedies in nurture. My suspicion, however, is that education policies are too often set by politicians to whom the glib slogan “leave no child behind” appeals precisely because it is so completely unobjectionable. But children will get left behind if we continue to insist that each one has the same potential for learning.

We do not as yet understand why some children learn faster than others, and I don’t know when we will. But if we consider how many commonplace biological insights, unimaginable fifty years ago, have been made possible through the genetic revolution, the question becomes pointless. The issue rather is this: Are we prepared to embrace the undeniably vast potential of genetics to improve the human condition, individually and collectively? Most immediate, would we want the guidance of genetic information to design learning best suited to our children's individual needs? Would we in time want a pill that would allow fragile X boys to go to school with other children, or one that would allow naturally slow learners to keep pace in class with naturally fast ones? And what about the even more distant prospect of viable germ-line gene therapy? Having identified the relevant genes, would we want to exercise a future power to transform slow learners into fast ones before they are even born? We are not dealing in science fiction here: we can already give mice better memories. Is there a reason why our goal shouldn’t be to do the same for humans?

One wonders what our visceral response to such possibilities might be had human history never known the dark passage of the eugenics movement. Would we still shudder at the term “genetic enhancement”? The reality is that the idea of improving on the genes that nature has given us alarms people. When discussing our genes, we seem ready to commit what philosophers call the “naturalistic fallacy,” assuming that the way nature intended it is best. By centrally heating our homes and taking antibiotics when we have an infection, we carefully steer clear of the fallacy in our daily lives, but mentions of genetic improvement have us rushing to run the “nature knows best” flag up the mast. For this reason, I think that the acceptance of genetic enhancement will most likely come about through efforts to prevent disease. …

All over the world government regulations now forbid scientists from adding DNA to human germ cells. Support for these prohibitions comes from a variety of constituencies. Religious groups—who believe that to tamper with the human germ line is in effect to play God—account for much of the strong knee-jerk opposition among the general public. For their part, secular critics, as we have seen, fear a nightmarish social transformation such as that suggested in Gattaca—with natural human inequalities grotesquely amplified and any vestige of an egalitarian society erased. But though this premise makes for a good script, to me it seems no less fanciful than the notion that genetics will pave the way to Utopia. …

My view is that, despite the risks, we should give serious consideration to germ-line gene therapy. I only hope that the many biologists who share my opinion will stand tall in the debates to come and not be intimidated by the inevitable criticism. Some of us already know the pain of being tarred with the brush once reserved for eugenicists. But that is ultimately a small price to pay to redress genetic injustice. If such work be called eugenics, then I am a eugenicist.

Over my career since the discovery of the double helix, my awe at the majesty of what evolution has installed in our every cell has been rivaled only by anguish at the cruel arbitrariness of genetic disadvantage and defect, particularly as it blights the lives of children. In the past it was the remit of natural selection—a process that is at once marvelously efficient and woefully brutal—to eliminate those deleterious genetic mutations. Today, natural selection still often holds sway: a child born with Tay-Sachs who dies within a few years is—from a dispassionate biological perspective—a victim of selection against the Tay-Sachs mutation. But now, having identified many of those mutations that have caused so much misery over the years, it is in our power to sidestep natural selection. Surely, given some form of preemptive diagnosis, anyone would think twice before choosing to bring a child with Tay-Sachs into the world. The baby faces the prospect of three or four long years of suffering before death comes as a merciful release. And so if there is a paramount ethical issue attending the vast new genetic knowledge created by the Human Genome Project, in my view it is the slow pace at which what we now know is being deployed to diminish human suffering. Leaving aside the uncertainties of gene therapy, I find the lag in embracing even the most unambiguous benefits to be utterly unconscionable. That in our medically advanced society almost no women are screened for the fragile X mutation a full decade after its discovery can attest only to ignorance or intransigence. Any woman reading these words should realize that one of the important things she can do as a potential or actual parent is to gather information on the genetic dangers facing her unborn children—by looking for deleterious genes in her family line and her partner’s, or, directly, in the embryo of a child she has conceived. And let no one suggest that a woman is not entitled to this knowledge. Access to it is her right, as it is her right to act upon it. She is the one who will bear the immediate consequences.

Two years ago, my views on this subject received a very cold reception in Germany. The publication of my essay, “Ethical Implications of the Human Genome Project,” in the highly respected newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), provoked a storm of criticism. Perhaps this was the editors’ intent: Without my knowledge, let alone consent, the paper had given my essay a new title devised by the translator as “The Ethic of the Genome—Why We Should Not Leave the Future of the Human Race to God.” While I subscribe to no religion and make no secret of my secular views, I would never have framed my position as a provocation to those who do. A surprisingly hostile response came from a man of science, the president of the German Federal Chamber of Medical Doctors, who accused me of “following the logic of the Nazis who differentiate between a life worth living and a life not worth living.” A day later, an editorial entitled “Unethical Offer” appeared in the same paper that had published mine. The writer, Henning Ritter, argued with self-righteous conviction that in Germany the decision to end the lives of genetically damaged fetuses would never become a private matter. In fact, his grandstanding displayed a simple ignorance of the nation’s law; in Germany today, it is solely the right of a pregnant woman, upon receipt of medical advice, to decide whether to carry her fetus to term.

The more honorable critics were those who argued openly from personal beliefs, rather than exploiting the terrifying specter of the German past. The respected German president, Johannes Rau, countered my views with an assertion that “value and sense are not solely based on knowledge.” As a practicing Protestant, he finds truths in religious revelation while I, a scientist, depend only on observation and experimentation. I therefore must evaluate actions on the basis of my moral intuition. And I see only needless harm in denying women access to prenatal diagnosis until, as some would have it, cures exist for the defects in question. In a less measured comment, the Protestant theologian Dietmar Mieth called my essay the “Ethics of Horror,” taking issue with my assertion that greater knowledge will furnish humans better answers to ethical dilemmas. But the existence of a dilemma implies a choice to be made, and choice to my mind is better than no choice. A woman who learns that her fetus has Tay-Sachs now faces a dilemma about what to do, but at least she has a choice, where before she had none. Though I am sure that many German scientists agree with me, too many seem to be cowed by the political past and the religious present: except for my longtime valued friend Benno Müller-Hill, whose brave book on Nazi eugenics, Murderous Science (Tödliche Wissenschaft), still rankles the German academic establishment, no German scientist saw reason to rise to my defense.

I do not dispute the right of individuals to look to religion for a private moral compass, but I do object to the assumption of too many religious people that atheists live in a moral vacuum. Those of us who feel no need for a moral code written down in an ancient tome have, in my opinion, recourse to an innate moral intuition long ago shaped by natural selection promoting social cohesion in groups of our ancestors. …

With its direct contradiction of religious accounts of creation, evolution represents science’s most direct incursion into the religious domain and accordingly provokes the acute defensiveness that characterizes creationism. It could be that as genetic knowledge grows in centuries to come, with ever more individuals coming to understand themselves as products of random throws of the genetic dice—chance mixtures of their parents’ genes and a few equally accidental mutations—a new gnosis in fact much more ancient than today’s religions will come to be sanctified. Our DNA, the instruction book of human creation, may well come to rival religious scripture as the keeper of the truth.

I may not be religious, but I still see much in scripture that is profoundly true. In the first letter to the Corinthians, for example, Paul writes:

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I have become sounding brass or a clanging cymbal.

And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing.

Paul has in my judgment proclaimed rightly the essence of our humanity. Love, that impulse which promotes our caring for one another, is what has permitted our survival and success on the planet. It is this impulse that I believe will safeguard our future as we venture into uncharted genetic territory. So fundamental is it to human nature that I am sure that the capacity to love is inscribed in our DNA—a secular Paul would say that love is the greatest gift of our genes to humanity. And if someday those particular genes too could be enhanced by our science, to defeat petty hatreds and violence, in what sense would our humanity be diminished?2

In addition to laying out a misleadingly dismal vision of our future within the film itself, the creators of Gattaca concocted a promotional tag line aimed at the deepest prejudices against genetic knowledge: “There is no gene for the human spirit.” It remains a dangerous blind spot in our society that so many wish this were so. If the truth revealed by DNA could be accepted without fear, we should not despair for those who follow us.

James Watson, DNA: The Secret of Life (Knopf, 2003), pp. 395-405.

The philosophers Ingmar Persson and Julian Savulescu have made a sustained case for this in the form of moral genetic enhancement: Unfit for the Future: The Need for Moral Enhancement (Oxford University Press, 2012).