The geopolitics of ultra-low fertility and techno-natalism: Visualized

Our paper in “Politics and the Life Sciences” visually summarized in 10 points

A picture is worth a thousand words. As such—while I invite you to read my article with Filipe Nobre Faria in Politics and the Life Sciences on the geopolitical and socioeconomic impact of reprotech in an age of fertility collapse—I have also put together this 10-point visual essay outlining the key trends and arguments. Enjoy!

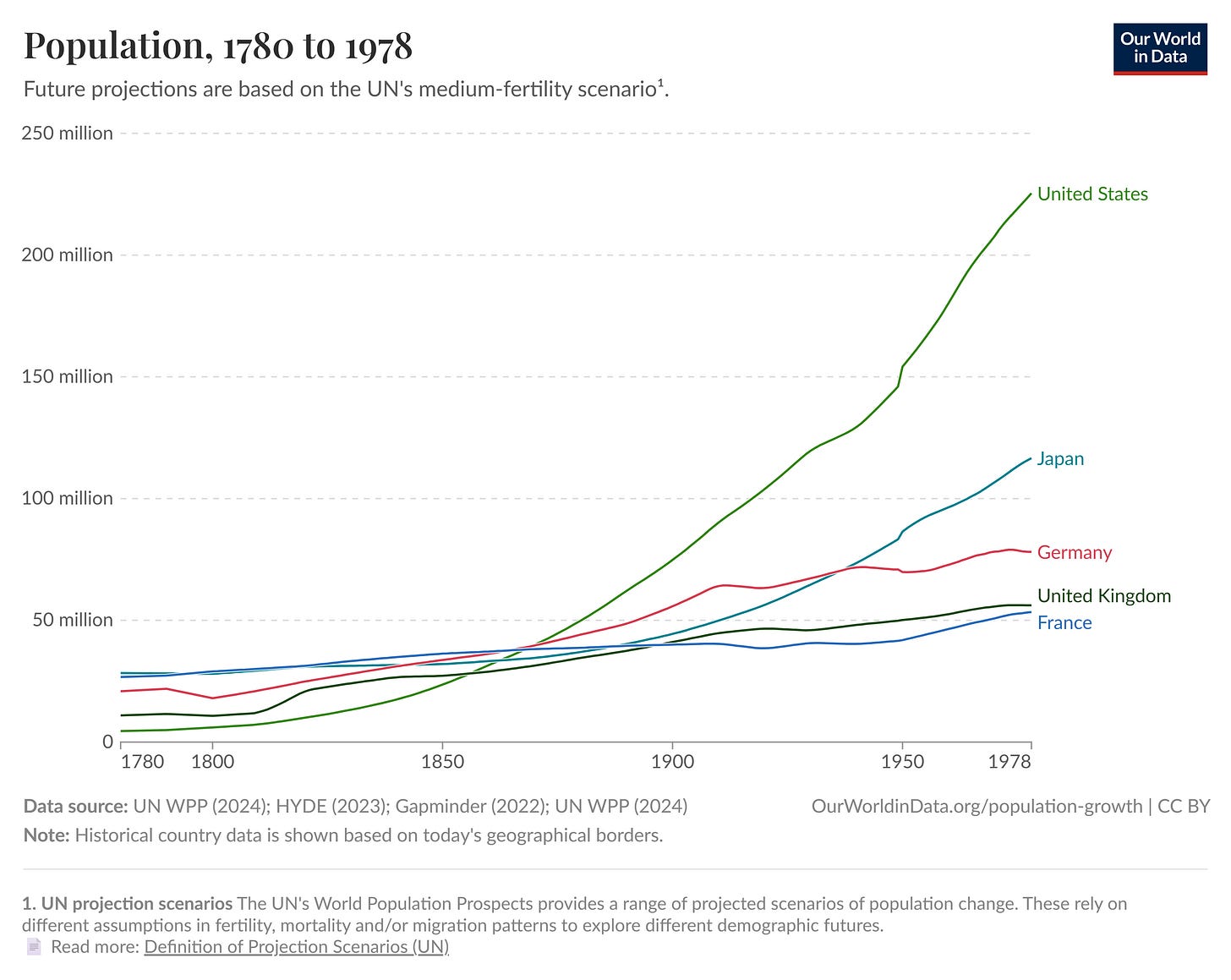

1. Population is a fundamental driver of national power

For any given level of economic development and social organization, population is a fundamental variable of national power.1 Population growth differentials are necessary (though not sufficient) drivers for the rise of the U.S. as a superpower since the 18th Century and the severe relative decline of France in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The contribution of population to national power has been recognized by statesmen and political scientists as varied as Aristotle, Ben Franklin and other Founding Fathers, Tocqueville, Charles de Gaulle, and Lee Kuan Yew.

It is true that many populous countries, due to institutional failure and/or weak human human capital, are geopolitically underwhelming. And, as one of our reviewers pointed out, relatively small states like 5th-century BC Athens or 18th-century England can sometimes punch massively above their weight. However, over the long run, such exceptional small states tend to lose their advantage as their innovations diffuse to other, larger countries. Population, economics, and relatedly technology all matter to power. As Abraham Lincoln said on which nations tend to win: “I believe in the Providence of the most men, the largest purse, and the longest cannon.”

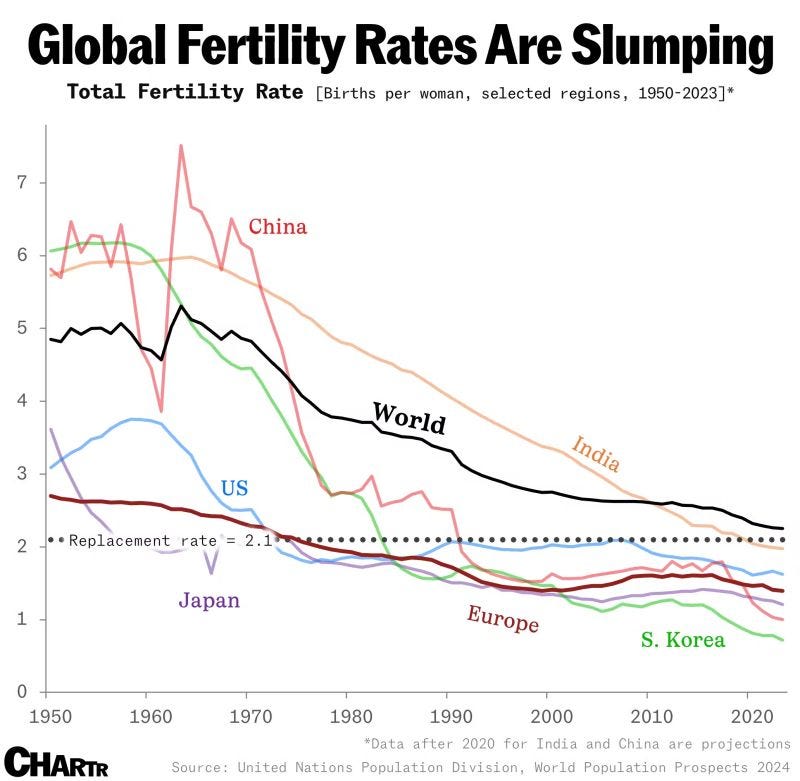

2. Sub-replacement fertility has gone global

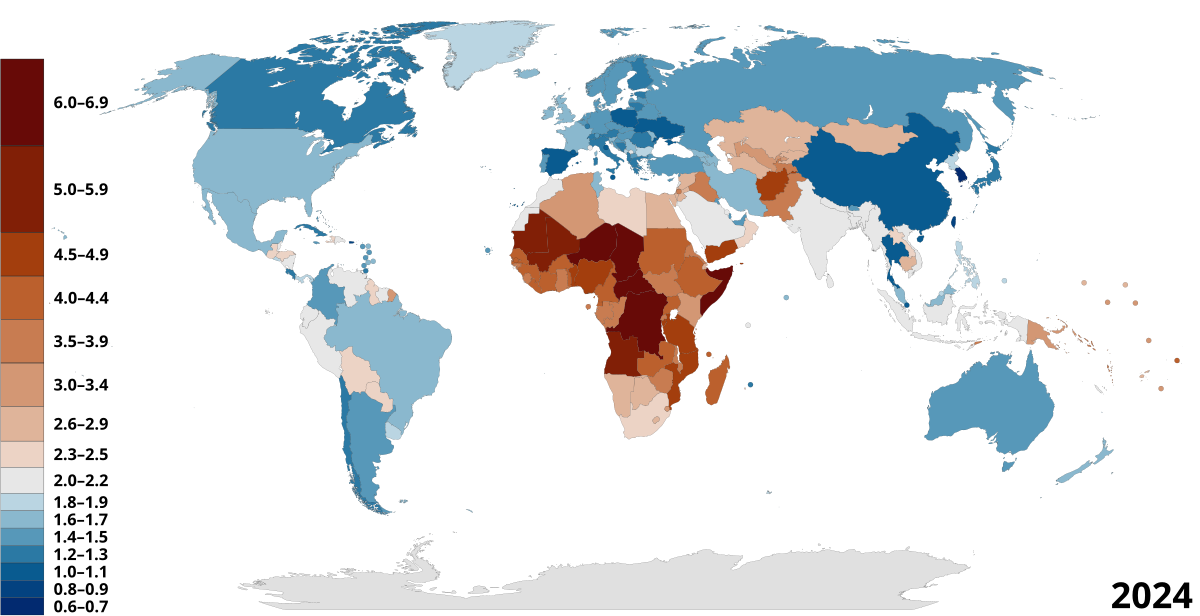

After a long population explosion, the world has entered a phase of sub-replacement fertility, and sometimes ultra-low fertility (1.4 children or less per woman), in most countries. Sub-replacement fertility affects every economically prosperous and techno-scientifically innovative country in the world, with the notable exception of Israel.

A striking recent trend however is that low fertility does not only concern the most developed countries, but also many lower- and middle-income countries in Latin America, South and Southeast Asia, and even parts of North Africa and the Middle East (Tunisia, Iran). High fertility is now largely restricted to sub-Saharan Africa and parts of the Muslim world.

3. The Global North (including China) is collapsing

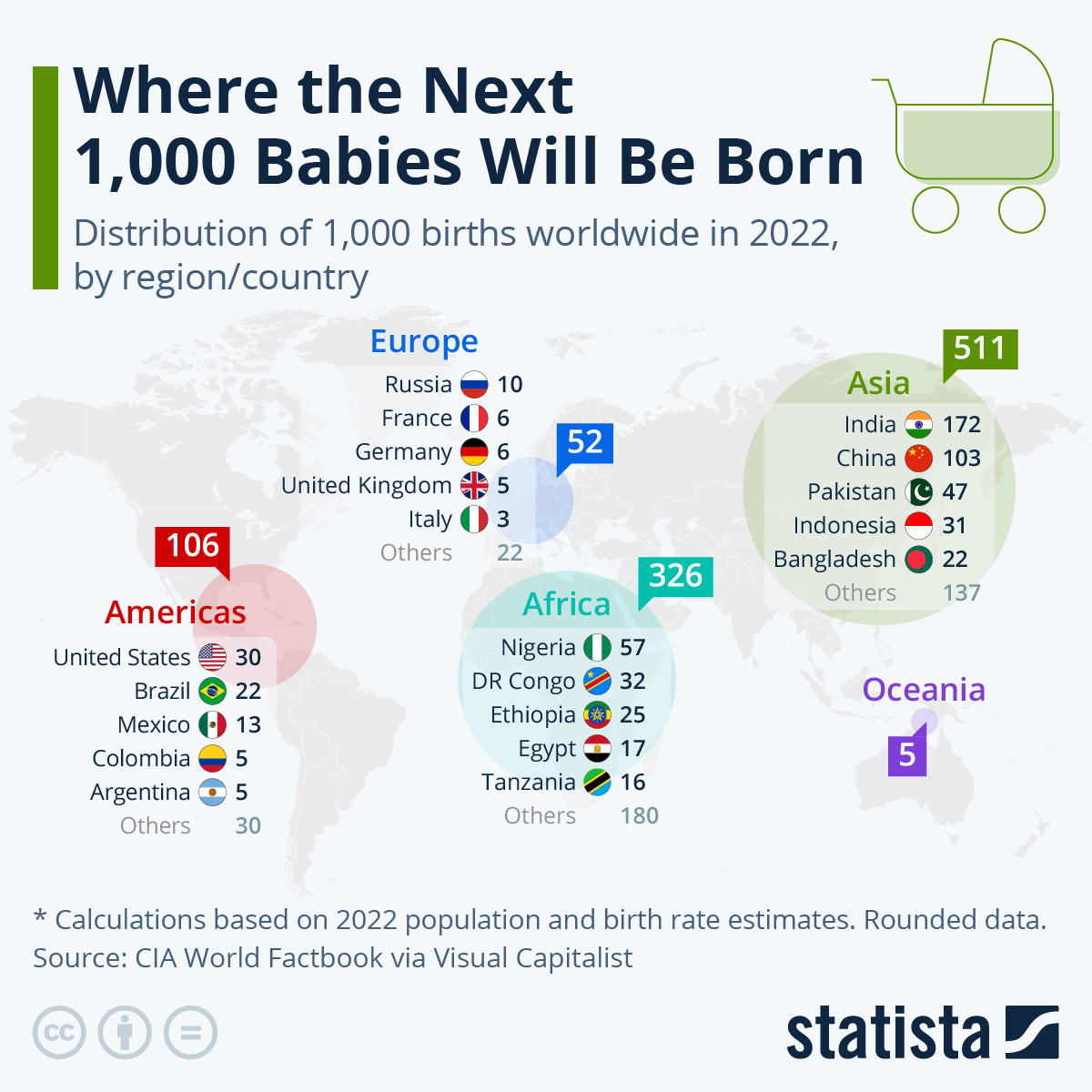

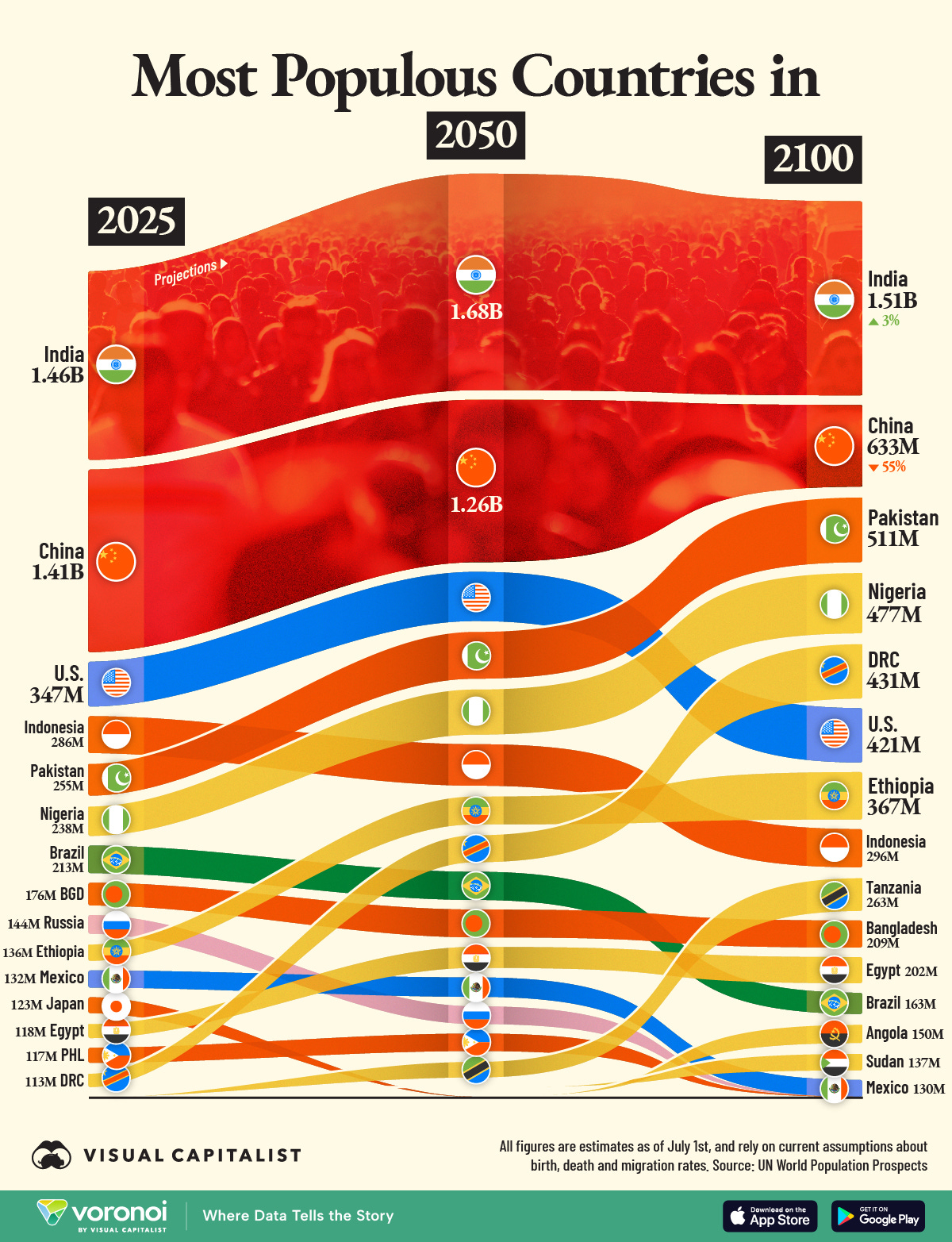

The babies of today represent the humanity of tomorrow. Did you know that India now makes almost twice as many babies as China? Or that Indonesia and Congo each make more babies than the entire European Union? Or that Nigeria and Pakistan each make about as many babies as all of Europe? Long before the end of the century, such demographic differentials will have obvious geopolitical impacts.

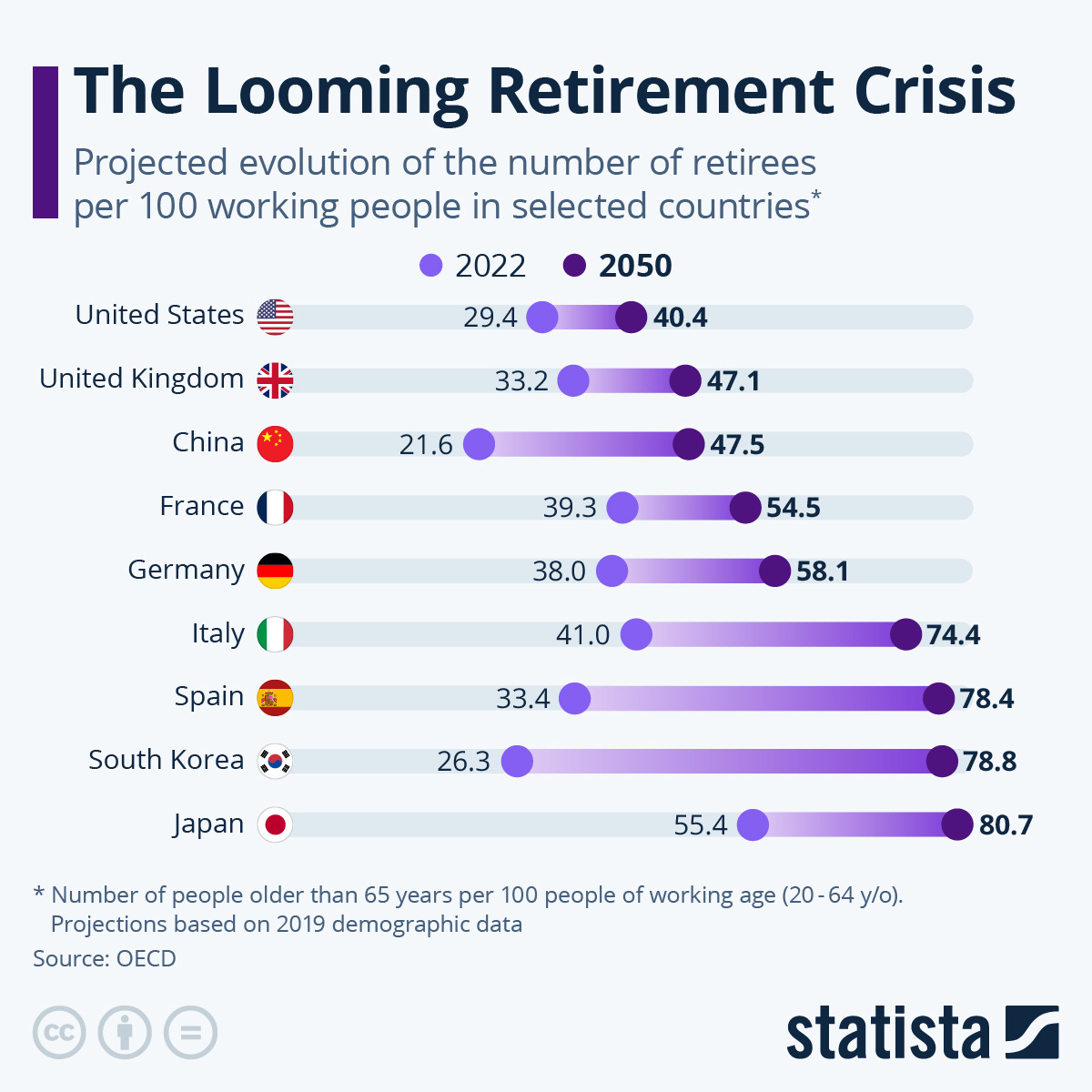

4. Shrinking labor forces and rising elderly costs paralyze nations

In sub-replacement countries, shrinking workforces must bear the pension and healthcare costs of ballooning elderly populations, reducing the resources available to project onto the international scene. This trend is already severely impacting Italy and Japan, but will also become very visible in countries like Russia, South Korea, and eventually China. Countries that are able to slow these trends through higher births and productive immigration2 will retain geopolitical capacity for longer.

Significantly, all of the most economically developed and techno-scientifically innovative countries, except Israel, have sub-replacement fertility. Adverse demographics means that over time such nations will be less able to contribute to global public goods such as foreign aid or innovation. The latter is crucial because, in my view, global challenges like environmental degradation and infectious disease are mostly likely to be solved through innovation (and not the imposition of national sacrifices whose benefits are diluted globally).

5. Reprotech can increasingly foster population growth, genetic health, and enhancement

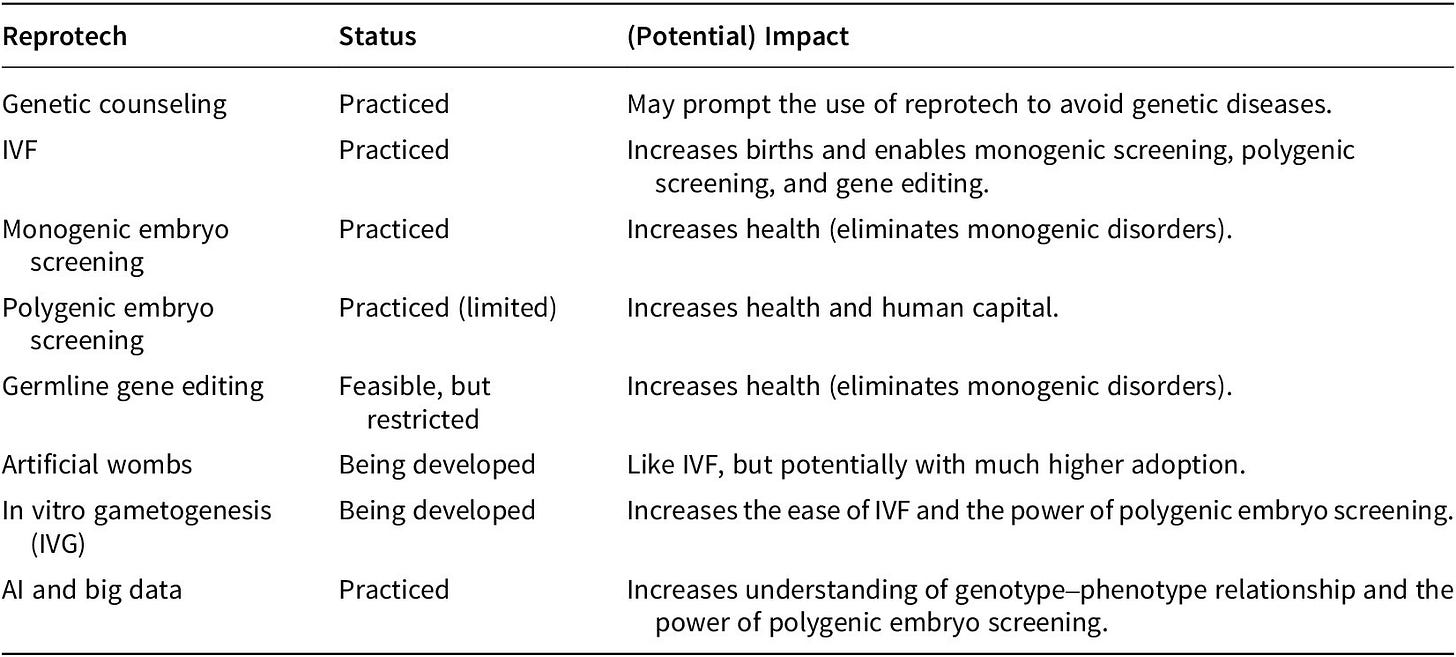

Reprotech has the potential to sustain or increase the size of working-age populations, reduce genetic diseases and their associated healthcare costs and productivity losses, and increase human capital (arguably the most fundamental driver of economic growth, technological innovation, and societal capacity).

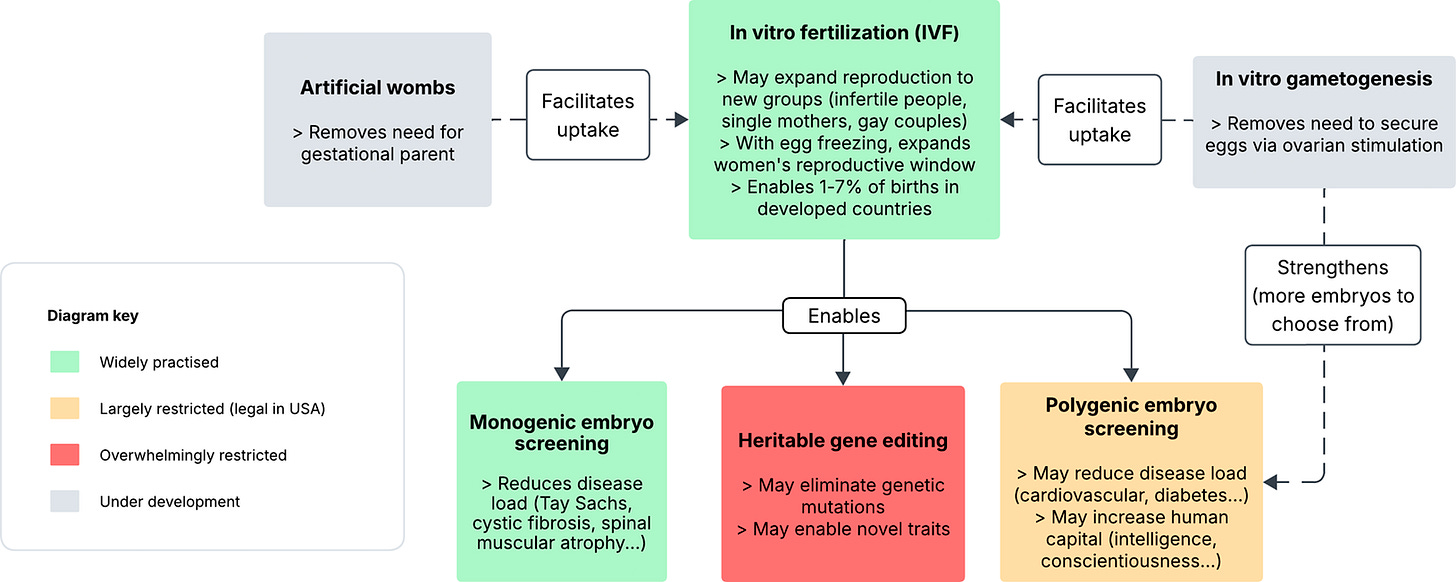

Already, reprotechs such as intra-uterine insemination, IVF, and egg freezing can significantly prolong women’s fertility window and enable subfertile people, single women, lesbian couples, and (through surrogacy) gay couples to have children. Cheap genetic sequencing enables detection of genetic conditions and creates reams of genetic data. AI is also helping us to make sense of this data and better understand the often maddeningly complex relationships between genes and phenotypic traits such as cardiovascular disease, schizophrenia, and intelligence. Gene editing is also now possible, though taboo.

These achievements already seem worthy of science fiction. But more is on the horizon, such as artificial wombs and in vitro gametogenesis (IVG, creation of sperm or egg from other cells, has already been used to create offspring in mice). Both artificial wombs and IVG would radically improve the accessibility of reprotech as one would no longer need the burdens and risks of pregancy and/or of extracting a handful of eggs through ovarian stimulation. As reprotech becomes more genetically powerful and accessible, so its geopolitical impact will increase.

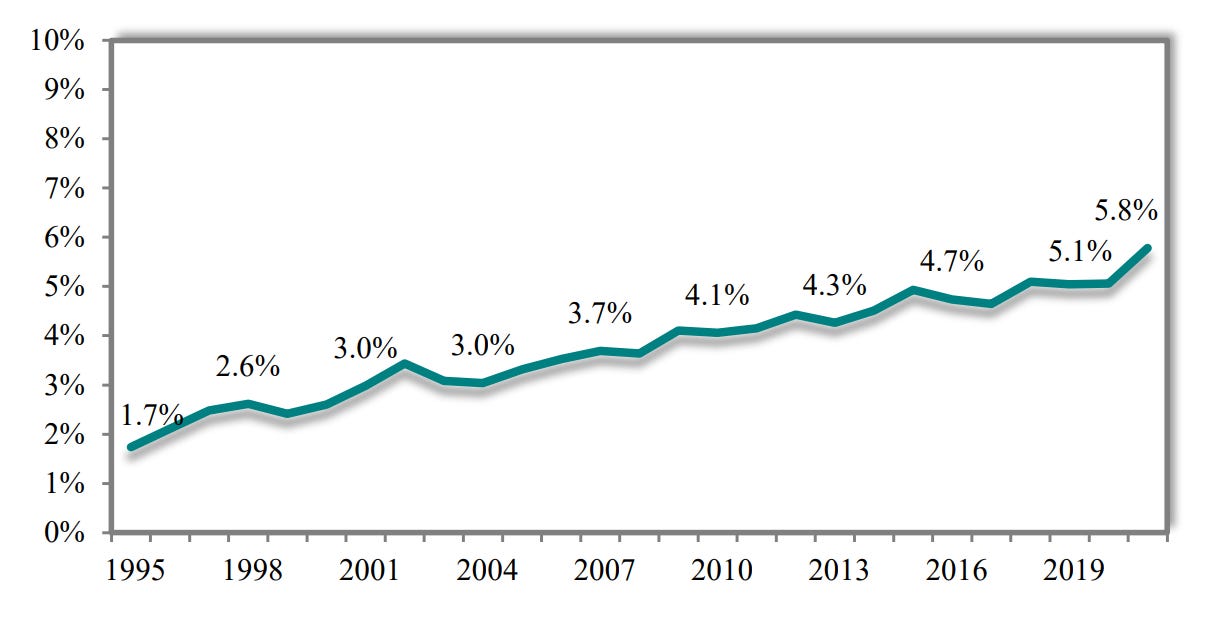

6. Reprotech’s current geopolitical impact is marginal, but growing

The current geopolitical impact of reprotech worldwide is marginal: IVF contributes to 1-2% of births in developed countries. However the impact of IVF in pro-reprotech nations is no longer negligible, contributing to 6-7% of all births in Denmark and Israel. Whether one likes it or not, enthusiastic adoption of reprotech has helped Israel achieve its population goal of a secure Jewish-majority state in the Middle East.

Again in Israel, largescale genetic testing and embryo screening has enabled a dramatic reduction of monogenic diseases like Tay Sachs among Ashkenazi Jews newborns and Beta Thalassemia among Arab newborns.

Even if adoption remains at a fairly modest level in absolute numbers, reprotech’s impact may become geopolitically significant if only because fertility rates are otherwise so low, especially in the most innovative and powerful countries. Assuming the growth of IVF adoption remains consistent, almost 400 million additional people could be born by 2100—not a negligible amount!

7. Governments are increasingly promoting access to reprotech to support population growth

Governments in sub-replacement countries are increasingly promoting access to reprotech to boost birth rates. France is looking to fight infertility in support of the nation’s longstanding pronatalist tradition. China is broadening insurance coverage of reprotech to boost births as part of the Three-Child Policy. Perhaps surprisingly, there is even an emerging bipartisan consensus on support for IVF in the heavily polarized USA. The pronatalist Trump administration has said it will expand support for IVF: “Because we want more babies, to put it very nicely.”

One can also imagine distinctly creepy scenarios. Would authoritarian governments like China and North Korea be willing to create state-run artificial womb farms to raise parentless children for the good of the nation? Not impossible.

8. Medical genetics is being routinized

Medical genetics and genetic counseling are expanding across the world. As documented by our Repronews newsletter, genetic studies of subpopulations are proliferating to more and more countries and subgroups. Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) is even planning to genetically sequence every newborn in England to identify diseases, predict disease risk, and provide personalized care. The expansion of biobanks of genetic and phenotypic datasets, combined with steadily growing AI capabilities, will improve our understanding of human genetics in ways that inform reprotech.

9. Reprotechs are often mutual enablers of one another

Many emerging reprotechs are mutual enablers one another. In particular, artificial wombs and IVG could both radically increase the ease of using reprotech, leading to a tipping point towards mass adoption. Legal scholar Hank Greely has predicted that “Easy PGD” (easy preimplantation genetic diagnosis) could become the norm once IVG becomes available. This would mean creating any number of early-stage embryos and then selecting for implantation the one with the most genes associated with health and other desired traits.

The genetic power of reprotech will increase over time. For example, while current polygenic embryo selection might enable a 2- to 3-point average increase in IQ, selection from a larger number of embryos and progressively improving understanding of the links between genes and phenotypes could lead to significantly higher potential gains. It may be that one day many societies come to see the unnecessarily randomized creation of human beings as barbaric.

10. Adoption of reprotech will vary widely

There is no expectation that countries will equally adopt reprotech breakthroughs. Indeed, a major theme of my research is that different ethical and religious philosophies (such as Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism) have varying attitudes towards reproduction that have had significant genetic impacts historically and continue to influence attitudes towards use of reprotechs today.

Adoption will depend on:

Nations’ biotechnological capabilities. These are strongest in North America, Europe, East Asia, Israel, the Arab Gulf states. Elites in countries like India are also likely to access reprotech.

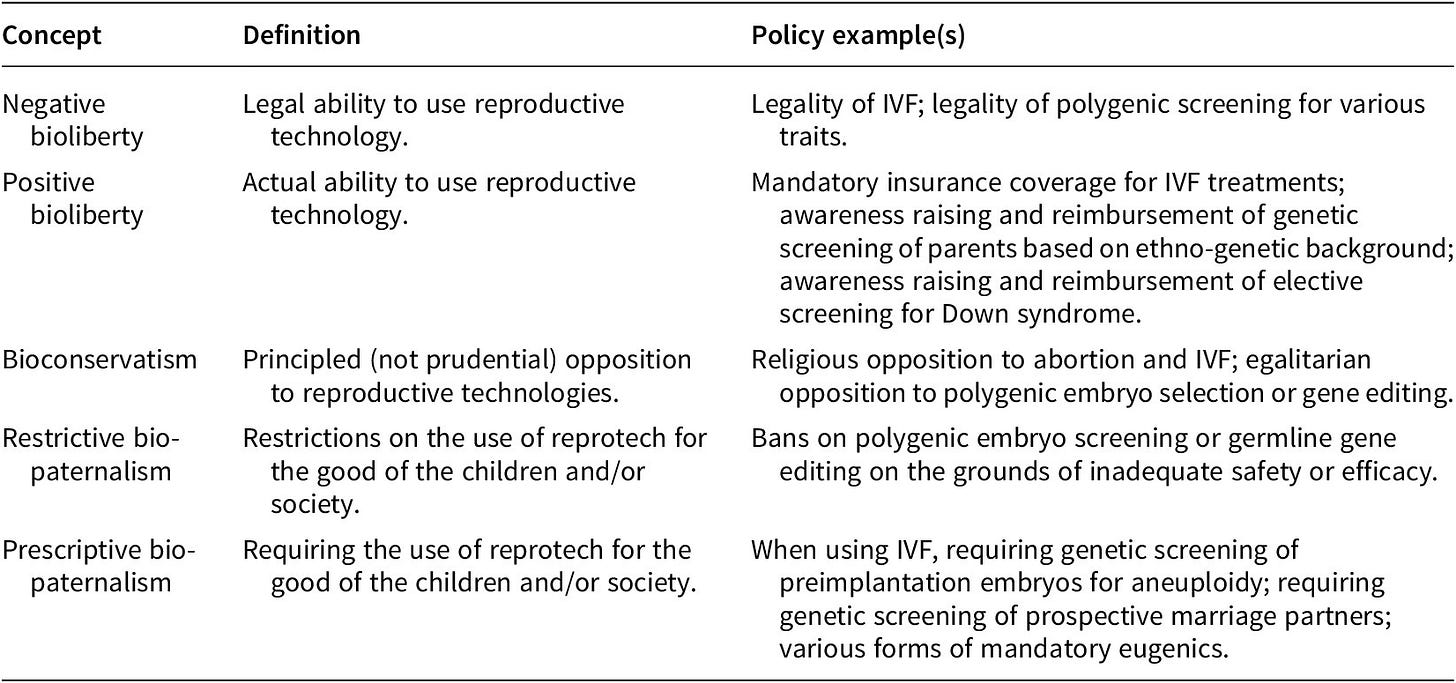

Nations’ differing policies and values. These can include policy goals such as boosting birth rates and promoting genetic health, as well as balancing values such as freedom (reproductive), equality (motivating equal access to reprotech and/or suppression of genetic enhancement), and the sanctity of early-stage human life (severely restricting use of reprotech as “exploitative,” as in Germany).

Today, Germany and Israel represent opposite poles of the reprotech policy spectrum. Learning the exact opposite lessons from the Holocaust, Israelis have enthusiastically embraced reprotech to foster a healthy and growing Jewish population, while Germans have largely rejected reprotech as violating human dignity and proximity to “eugenics,” not to mention rejecting ethno-natalism in general.

Insofar as policies and values affecting reprotech adoption directly impact both the gene pool and nations’ overall geopolitical competitiveness, these offer a paradigmatic example of gene-culture coevolution.

In term of current trends, we can reasonably predict:

Mass adoption of reprotech is likely to initially occur in countries combining biotechnological capabilities with a heavy genetic disease load due to a history inbreeding. This would include Israel, the Gulf Arab states, and (at least for elites) India.

The U.S. is likely to continue to pioneer development of the most innovative reprotechs, due to unmatched biotech capabilities, a critical mass of wealthy consumers, a thriving venture capital and startup scene, and lack of restrictive regulation. Mass adoption seems unlikely for the foreseable future however.

Scholars like Alexis Heng Boon Chin have argued that, unless restricted, Confucian societies like China and Singapore are likely to embrace reprotech for genetic enhancement (which he calls “Confugenics”), driven by status-obsessed competitiveness. This will however very much depend on government choices (historically often restrictive).

In conclusion, while the world is affected by many profound trends—climate change, infectious disease threats, AI, and old fashioned wars and power-political rivalries—population should not be neglected. Population trends will continue to be crucial for the power imbalances and the course of many conflicts, such as those between Ukraine and Russia or between Israel and the Palestinians. At a most fundamental level, reproductive trends will determine who we are as a species.

When considering the future power of the U.S., the EU, China, Russia, and other polities, population trends, and increasingly reprotech, will be a critical factor. As such, scholars should further explore the current and potential impact of emerging reprotechs on socioeconomic systems and geopolitics. What may be relatively marginal today may have outsized impact in the future.

At the risk of appearing overly reductionist, national power tends to correspond to the following formula:

National Power = Population * Human Capital * Market Institutions (including predictable property rights and social trust/low corruption)

At any rate, with such an equation I would argue one can account for much of the decline of the British Empire (Britain was massively overleveraged), the Soviet Union, and the EU, the rise of China, the underperformance of other BRICS, and the basic resilience of U.S. power. Such an equation also makes predictions about future power trends.

It should be noted that much immigration is in fact economically counterproductive for the host nations. In Denmark and the Netherlands, the average fiscal impact of immigrants from Africa and the Middle East is negative, reflecting low-skill immigration and relatively high welfare use. The situation is likely similar in most west-European countries. The level of productive immigration needed to make up for fertility collapse seems well beyond the political capacity and societal willingness of European states. By contrast, small and economically open illiberal states like Singapore and the Gulf states have pioneered more unsentimental models of productive mass guest-worker immigration, but these are careful not to give welfare or citizenship to foreigners if these are deemed unbeneficial to the host nation.

Mandatory eugenic policy will obviously be a crucial factor in the most successful social structures to come, if for no other reason than its unjustly-ignored incredible potential for raising a nation’s capabilities nigh infinitely. It will likely involve government incentives for sterilization of undesirables in exchange for welfare, using sperm and egg donation to allow a few elite genetic specimens to make up a vastly disproportionate percentage of the every new generation, etc. A nation with such stringent control over breeding will likely have little trouble with fertility rates - not that it matters much, since 99% of the population being winnowed out is a good thing! They’re simply not adapted to post scarcity conditions, which is effectively already possible.

Even something as boring and basic as cloning Von Neumann 50 times is invaluable.