Understanding the AI Revolution in China

5 Take-Aways from Kai-Fu Lee’s “AI Superpowers”

This is a great little book for understanding how artificial intelligence (AI), perhaps the most consequential technology of this century, is rapidly developing in China, the world’s new scientific superpower and by some metrics already the largest economy.

Kai-Fu Lee writes on his subject with style and ease on the back of a lifetime of experience. Born in Taiwan in 1961, he earned a PhD in computer science at Carnegie Mellon and and worked for a string of Silicon Valley companies, before becoming head of Google China in 2005. Since then, he has become a prominent tech personality in China and a major venture capitalist (his Sinovation Ventures has over $2 billion in assets).

The following are a few take-aways from the book that struck me and that will be relevant to Western policymakers:

1. China’s business culture is brutal

Perhaps the most striking part of the book for me was the difference in business culture between the two dominant tech players in the world, Silicon Valley and China. We’re not used to thinking of U.S. tech giants (which the French call les GAFAM, short for Google, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft) as particularly “nice.” We fault them for their aggressively addictive design, tax avoidance through creative international accounting, and (ab)use of patent law.

Much tech policy in Brussels revolves around regulating these giants’ behavior and inflicting fines for monopolistic practices and other misbehavior, no easy thing when these companies have acquired the wealth, power, and influence of quasi-state actors.

Bad as this may be, Lee shares many chilling stories about the way of doing business in China that make our Silicon Valley tech-bros seem like softies. The predominant impression is one of a widespread amorality.

For example, what Westerners might consider a totally shameless stealing of an idea, Chinese will consider to be providing the same service more efficiently and therefore fair game. This can go very far. In China, simply cloning a Silicon Valley or Chinese competitor’s website—down to the last pixel!—was (is?) considered an acceptable practice. In one case, a company reproduced a competitor’s website (using the same name), put a more intuitive URL, and siphoned away all new users until the original went out of business. Lee provides many other examples of similar unscrupulous behavior as well as dirty legal tricks in China’s brutal business environment.1

The combination of workaholism, drive, and ruthlessness have contributed to the dynamism Chinese business and their provision of cutting-edge goods and services. However, the amorality and unscrupulous practices make it understandable that many foreign governments and businesses have become less willing to work with Chinese counterparts.2

Lee emphasizes that while Western companies will be somewhat “mission driven” (however cynical employees may be about their corporate mission statements), Chinese companies are purely driven by money:

In stark contrast, China’s startup culture is the yin to Silicon Valley’s yang: instead of being mission-driven, Chinese companies are first and foremost market-driven. Their ultimate goal is to make money, and they’re willing to create any product, adopt any model, or go into any business that will accomplish that objective. That mentality leads to incredible flexibility in business models and execution, a perfect distillation of the “lean startup” model often praised in Silicon Valley. It doesn’t matter where an idea came from or who came up with it. All that matters is whether you can execute it to make a financial profit. The core motivation for China’s market-driven entrepreneurs is not fame, glory, or changing the world. Those things are all nice side benefits, but the grand prize is getting rich, and it doesn’t matter how you get there.

Chinese tech companies are more ruthless, more willing to go the extra mile, more willing to integrate different services,3 and more willing to create brick and mortar services than their Silicon Valley counterparts. Their application and drive make them formidable indeed.

2. We live in an age of AI application, not innovation

The book also provides an interesting overview of the state of AI research and businesses, as of 2018. Lee sees the current explosive growth of the AI sector as driven primarily by ever-more extended application of existing AI methods—especially the pattern recognition enabled by deep learning—rather than major innovations. Breakthroughs in AI have only come every couple decades and there have been many “AI winters” where the technology stagnated for years. He is not bullish on the Singularity.

Applying AI today requires computing power, lots of data, and narrow missions. All of these conditions are currently met given the state of our hardware and our massive use of digital tools today in virtually all fields. Lee argues that this emphasis on application, rather than innovation, works to China’s strengths:

Moving from discovery [of AI] to implementation reduces one of China’s greatest weak points (outside-the-box approaches to research questions) and also leverages the country’s most significant strength: scrappy entrepreneurs with sharp instincts for building robust businesses.4

3. The Chinese government is going all-in on AI

Lee provides some interesting insights into the workings of the Chinese government, which as a continent-sized one-party state is downright strange and mysterious for Westerners. The Chinese government is centralized in sending broad political signals and the setting of goals but, by the country’s sheer size, decentralized in their implementation. Local party officials try apply at local level what will get them kudos at the central level.5

The United States’ rise to hegemony in tech took place without much of a national strategy, but was essentially driven by the private sector (albeit kickstarted by technological spillover from public sector research). In China by contrast, Lee argues the shift to tech entrepreneurship could only occur under government leadership because the society had to be jolted into a change of mindset. He credits in particular the government’s 2014 mass campaign promoting innovation for shifting a conformist, scarcity-focused Chinese culture towards an embrace of tech entrepreneurship (with all the individual risk that it entails):

China’s mass innovation campaign [created the only true counterweight to Silicon Valley] by directly subsidizing Chinese technology entrepreneurs and shifting the cultural zeitgeist. It gave innovators the money and space they needed to work their magic, and it got their parents to finally stop nagging them about taking a job at a local state-owned bank. … The government endorsement and [Jack] Ma’s example of internet entrepreneurship were particularly effective at winning over some of the toughest customers: Chinese mothers. In the traditional Chinese mentality, entrepreneurship was still something for people who couldn’t land a real job. The “iron rice bowl” of lifetime employment in a government job remained the ultimate ambition for older generations who had lived through famines. In fact, when I had started Sinovation Ventures in 2009, many young people wanted to join the startups we funded but felt they couldn’t do so because of the steadfast opposition of their parents or spouses.

Suddenly, all across China startup hubs, tech investment schemes, and vast digital city projects were launched. While Lee concedes must of this spending may end up being wasteful, he feels the results may be superior to that produced by the hostile attitude towards public investment in the United States (where the divisive political culture means major promising projects are often shut down).

Lee notes that while the Chinese government’s authoritarianism may limit research in the humanities and social science, this is not so for the hard sciences. He characterizes the country as “techno-utilitarian,” which means AI and other new technologies are likely to be pragmatically embraced with more enthusiasm than in the West, where researchers and entrepreneurs may be more limited by social, privacy, and other human-rights concerns.

4. It is unclear what kind of world will emerge from AI

Towards the end of the book, Lee includes many reflections on the kind of society the development of AI will lead to. The immediate functionalities seem positive: AI is already helping doctors detect cancers, may transform our transportation systems through self-driving cars, and even unleash creativity through digital art.

The flip side of this will be mass automation on an unprecedented scale. Lee estimates that 40-50% of jobs may disappear in this way within 20 years and he warns that AI “won’t discriminate by the color of one’s collar.” Highly skilled workers will not necessarily be secure.

What’s more, because of network effects, tech sectors tend to be “winner-take-all,” leading to the domination of just a few companies. This is deepening inequalities and leading to profound power asymmetries between those countries that have strong tech sectors (especially the United States and China) and everyone else. (For a book with the word “superpowers” in the title, I was a bit disappointed at how little it discusses the geopolitical aspects and international relations.)

Lee describes having had his own personal epiphany since being diagnosed with lymphatic cancer in 2013: having been a relentlessly utilitarian workaholic throughout his life, the prospect of death led him to recenter his life around compassionate engagement with his relatives and the people around him rather than abstract goals.

Socially, Lee suggests moving towards what you might call a “compassion economy” where the profits of automated companies are redistributed to people doing social and human-centered work, whether coaches, family oral historians, lactation consultants… Roles that improve human life and give it meaning. The suggestions are intriguing but the conversation remains wide open.

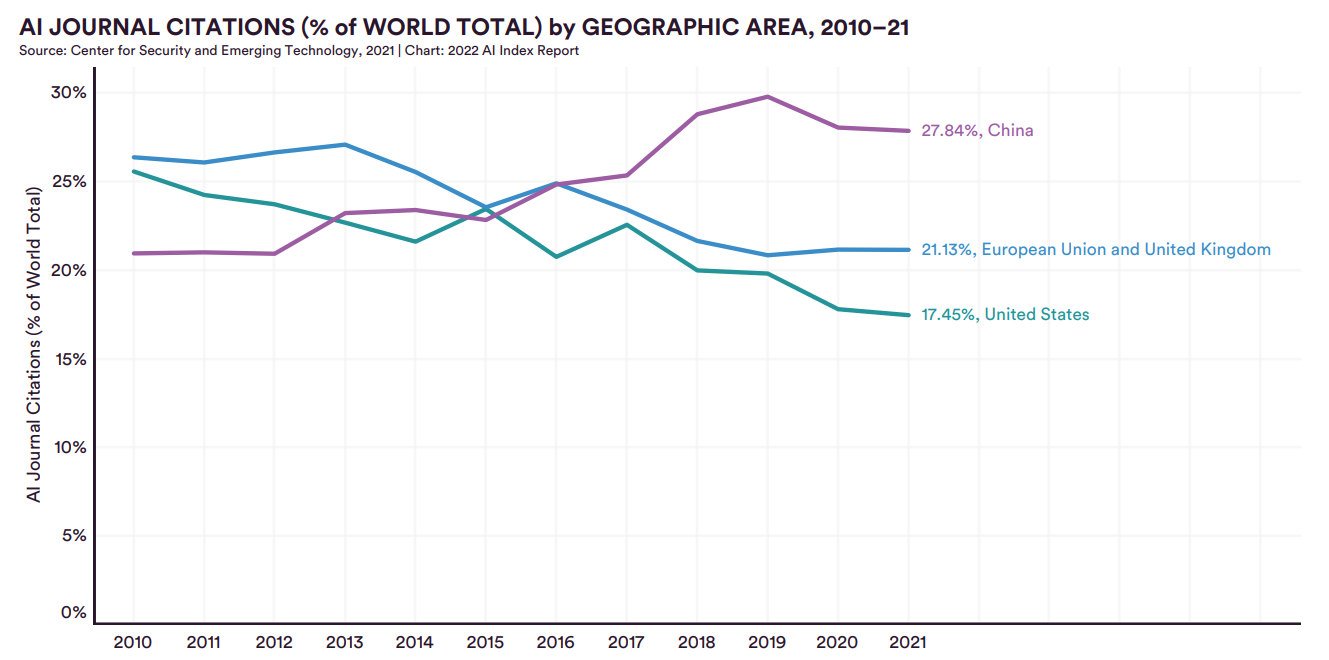

5. China can lastingly surpass Western technological prowess

I apologize to my readers if this seems like old news, but it bears repeating. The drive, intelligence, and sheer number of Chinese scientists, entrepreneurs, and engineers means that China is likely to become the chief scientific and technological power this century.

Lee may sometimes be too bullish on China. The country’s tech companies might have more data from Chinese consumers than United States and the European Union put together, but it’s not clear that this data will be applicable to other markets.6

And to what extent will Chinese AI companies be able to expand to other markets anyway? Silicon Valley has the advantage of a long history of being able to appeal overseas. This is further facilitated by their adaptation to European regulation, which often serves as a decent baseline for consumer protection everywhere else.

The West also has one advantage over China in terms of technology: it is far more likely to be able brain-drain skilled labor from other countries, to some extent including China itself.

Be that as it may, the rise of China as an equal or superior scientific and technological powerhouse is something Westerners—so used to being politically and morally in charge of world affairs—will have to really wrap their heads around. Lee provides a delightful historical example of how the Chinese can emulate and surpass Western technical prowess:

Twice a day, the Hall of Ancestor Worship comes alive. Located within Beijing’s Forbidden City, this was where the emperors of China’s last two dynasties once burned incense and performed sacred rituals to honor the Sons of Heaven that came before them. Today, the hall is home to some of the most intricate and ingenious mechanical timepieces ever created. The clock faces themselves convey expert craftsmanship, but it’s the impossibly complex mechanical functions embedded in the clocks’ structures that draw large crowds for the morning and afternoon performances.

As the seconds tick by, a metal bird darts around a gold cage. Painted wooden lotus flowers open and close their petals, revealing a tiny Buddhist god deep in meditation. A delicately carved elephant lifts its trunk up and down while pulling a miniature carriage in circles. A robotic Chinese figure dressed in the coat of a European scholar uses an ink brush to write out a Chinese aphorism on a miniature scroll, with the robot’s own handwriting modeled on the calligraphy of the Chinese emperor who commissioned the piece.

It’s a dazzling display, a reminder of the timeless nature of true craftsmanship. Jesuit missionaries brought many of the clocks to China as part of “clock diplomacy,” an attempt by Jesuits to charm their way into the imperial court through gifts of advanced European technology. The Qing Dynasty’s Qianlong emperor was particularly fond of the clocks, and British manufacturers soon began producing clocks to fit the tastes of the Son of Heaven. Many of the clocks on display at the Hall of Ancestor Worship were the handiwork of Europe’s finest artisanal workshops of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These workshops produced an unparalleled combination of artistry, design, and functional engineering. It’s a particular alchemy of expertise that feels familiar to many in Silicon Valley today.

While working as the founding president of Google China, I would bring visiting delegations of Google executives here to see the clocks in person. But I didn’t do it so they could revel in the genius of their European ancestors. I did it because, on closer inspection, one discovers that many of the finest specimens of European craftsmanship were created in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, which was then called Canton.

After European clocks won the favor of the Chinese emperor, local workshops sprang up all over China to study and recreate the Western imports. In the southern port cities where Westerners came to trade, China’s best craftspeople took apart the ingenious European devices, examining each interlocking piece and design flourish. They mastered the basics and began producing clocks that were near-exact replicas of the European models. From there, the artisans took the underlying principles of clock-building and began constructing timepieces that embodied Chinese designs and cultural traditions: animated Silk Road caravans, lifelike scenes from the streets of Beijing, and the quiet equanimity of Buddhist sutras. These workshops eventually began producing clocks that rivaled or even exceeded the craftsmanship coming out of Europe, all while weaving in an authentically Chinese sensibility.

Lee had his own negative experience with a clone competitor while head of Google China:

The [Chinese news] program showed users searching Google’s Chinese site for medical information being served up ads with links to fake medical treatments. … Google China was thrown into a full-on crisis of public trust. After watching the footage, I raced to my computer to conduct the same searches but curiously could not conjure up the results featured on the program. … I was immediately flooded with messages from reporters demanding an explanation as to Google China’s misleading advertising, but I could only give what probably sounded like a weak excuse: Google works quickly to remove any problematic advertisements, but the process isn’t instantaneous, and occasionally offending ads may live online for a few hours.

The storm continued to rage on, all while our team kept failing to find or locate the offending ads from the television program. Later that night I received an excited email from one of our engineers. He had figured out why we couldn’t reproduce the results: because the search engine shown on the program wasn’t Google. It was a Chinese copycat search engine that had made a perfect copy of Google—the layout, the fonts, the feel— almost down to the pixel. The site’s search results and ads were their own but had been packaged online to be indistinguishable from Google China. The engineer had noticed just one tiny difference, a slight variation in the color of one font used. The impersonators had done such a good job that all but one of Google China’s seven hundred employees watching onscreen had failed to tell them apart.

Failure to collaborate with China due to unscrupulous practices is not just a Western problem. In 1994, China and Singapore launched the Suzhou Industrial Park as joint investment project. Lee Kuan Yew, the prime minister of Singapore, had hoped that the local Chinese authorities would take on Singaporeans’ business culture, with an emphasis on “financial discipline, long-term master planning and continuing service to investors.” Instead, the Chinese used the Singaporeans to secure international business contacts and then… siphoned off their investment to the lower-cost neighboring Suzhou New District! Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: Singapore and the Asian Economic Boom (New York: HarperCollines, 2000), p. 651.

For example, Kai-Fu Lee describes WeChat as not just a messaging service but “the dominant social app in China … that evolved into a ‘digital Swiss Army knife’ capable of letting people pay at the grocery store, order a hot meal, and book a doctor’s visit.” WeChat has over 1.24 billion users and its parent company Tencent had revenue of $86.6 billion in 2021.

Kai-Fu Lee argues that relative lack of creativity and penchant for imitation in China has deep historical roots going back to Confucius:

Rote memorization formed the core of Chinese education for millennia. Entry into the country’s imperial bureaucracy depended on word-for-word memorization of ancient texts and the ability to construct a perfect “eight-legged essay” following rigid stylistic guidelines. While Socrates encouraged his students to seek truth by questioning everything, ancient Chinese philosophers counseled people to follow the rituals of sages from the ancient past. Rigorous copying of perfection was seen as the route to true mastery.

Students of history may note similarities with how past one-party dictatorships functioned in the West, notably the notion of “working towards the Führer.”

Lee notes for example that America and Chinese search habits were very different, at least when the Internet was introduced in China: whereas Americans users tended to focus on top search results (using Google like the Yellow Pages), Chinese users tended to click and explore all over the page (“like a shopping mall, a place to check out a variety of goods”).

It's fine to be a futurist but get a realistic picture of present China first, the one you depict as 'authoritarian,' 'techno-utilitarian,' and 'limited by human rights concerns' does not actually exist. There is not space to examine all three of these epithets, so let's take a quiz about the first one, 'authoritarian':

In what authoritarian country does the leader have the sole power to..

* Hire and fire the country's 5,000 top officials.

* Declare war. Frequently.

* Issue 300,000 national security letters (administrative subpoenas with gag orders that enjoin recipients from ever divulging they’ve been served);

* Control information at all times under his National Security and Emergency Preparedness Communications Functions.

* Torture, kidnap and kill anyone, anywhere, at will.

* Secretly ban 50,000 citizens from flying–and refusing to explain why.

* Imprison 2,000,000 citizens without trial.

* Execute 1,000 citizens each year prior to arrest.

* Kill 1,000 foreign civilians every day since 1951

* Massacre its own men, women and children for their beliefs

* Assassinate its own citizens abroad, for their beliefs.

* Repeatedly bomb and kill minority citizens from the air. (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/mar/02/duncancampbell) (https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/10/move-1985-bombing-reconciliation-philadelphia).

No Chinese leader, or group of leaders, has ever had one such power.

Mao was a total pussy. When they dropped him from the [Steering Committee] after the Great Leap Backward, he wandered around for months, moaning, "I feel like a mourner at my own funeral”.

Eventually they took him back, of course. But no Chinese politician or leader has ever killed another–a rule Mao laid down in 1929 and held steadfastly to thereafter. When war-hardened colleagues wanted to dispense with postwar legal niceties, Mao asked, “What harm is there in not executing people? Those amenable to labour reform should go and do labour reform so that rubbish can be transformed into something useful. Besides, people's heads are not like leeks. When you cut them off, they won’t grow again. If you cut off a head wrongly there is no way of rectifying the mistake even if you want to”.