Savulescu’s Singapore Study

Survey finds Singaporeans mostly willing to use embryo selection to boost intelligence

The National University of Singapore’s Julian Savulescu and his colleagues Casey Haining, Hui Jin Toh, and Owen Schaefer have released the results of their study (previewed in Repronews) on Singaporeans’ attitudes towards genetic enhancement for increased intelligence.

The study surveyed 1438 Singaporeans to gauge their willingness to use polygenic embryo selection (PES), gene editing, and SAT preparation courses to increase the chance of their child going to a top-100 university. As the authors note, recent developments in reprogenetic technologies are providing prospective parents “with increasing opportunities to influence their future child’s phenotype.”

The overwhelming majority of participants said IVF is either “morally acceptable” (48%) or “not a moral issue” (36%). Average willingness to an intervention to increase chance of their child going to a top-100 university was 57% for PES, 48% for germline gene editing, and 71% for SAT prep courses.

People with a degree were 8-9 percentage points less willing to use embryo selection or gene editing. Religious people were also less likely to support these practices, especially gene editing.

Stratified by ethnicity, Malays were mostly likely to support embryo selection (70%), while Chinese were most likely to support gene editing (50%).

The authors write (my bolding):

Compared with the equivalent U.S. study, our results suggest that, among a Singaporean population, there appears to be greater moral acceptance of, and greater willingness to use PES, gene editing, and SAT preparation courses to increase children’s chances of securing admission.

Such differences are likely to be attributable to differences in cultural values, particularly with respect to educational attainment. Singapore is a multiethnic, highly affluent society, which, like many East Asian countries, is influenced by Confucian values. This is reflected in Singapore’s hard-working culture, commitment to education, desire to attain better jobs and remuneration, and the fulfilment of cultural expectations to support multigenerational families. East Asian cultures are also renowned for their ‘tiger-parenting,’ a type of parenting characterised by an achievement-orientated nature and tight scheduling of educational activities, which is especially prevalent among the Chinese population.

Significantly, only 20% of Singaporeans thought PES for educational attainment was morally wrong, and only 31% thought gene editing was wrong, which suggests overall high acceptance among the population. Among the Singaporean sample, as was the case with the US sample, there appears to be greater acceptability of PES compared with gene editing. This may be because, unlike gene editing, PES does not require genetic manipulation or modification and is akin to picking a ‘winning ticket’ in a ‘genetic lottery’ based on the various possible combinations and permutations of genes that occur during fertilisation.

Furthermore, the Malay sample was significantly less supportive of gene editing (35%) compared with PES. Such differences may be attributable to the Islamic religion, given most Malays are Muslim . . . gene editing for the purpose of enhancement is forbidden in Islam, as it would imply altering Allah’s (Islamic God’s) creation. Since PES does not result in such alterations, manmade genetic alterations cannot be passed on and hence it may be more acceptable to that population. Moreover, the higher support for PES for cognitive enhancement among the Malay population may be influenced by sociocultural factors. Malays are a marginalised ethnic minority that are often outcompeted in higher education and jobs by other populations, and hence may see PES as a means to improve their children’s future opportunities.

The authors argue public acceptance is an important factor but not in-and-of-itself sufficient to justify introducing PES and gene editing for cognitive enhancement. Broader discussions with stakeholders and consideration of the technologies’ safety (especially for gene editing) and effectiveness are needed.

In particular, such techniques are based on insights from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that correlate particular genes with traits like IQ and educational attainment. However, most GWAS are currently used on European populations and so “may have limited generalisability to the Singaporean population.”

If and when reprogenetic enhancement becomes available, cultural competitiveness and market dynamics could make Singapore a leading adopter:

Chin et al have argued that Singapore’s heavy financial investment in education and pressure to succeed academically is likely to incentivise the use of such genetic technologies to improve the chances of academic success. Accordingly, the authors posited that this creates a potential for a particularly lucrative market for the widespread application of PES in Singapore and have called for regulatory safeguards to prevent the misuse of PES and safeguard the welfare and interests of the Singaporean population. Importantly, given that such technology is currently being used internationally, severe restrictions or a complete ban of the technology may encourage medical tourism. This, in turn, could exacerbate concerns surrounding social inequality, as without subsidies, only the most affluent would be able to access PES.

Cultural differences leading to differential adoption of reprogenetic technologies, thus leading to divergent evolutionary trajectories of different societies, are a paradigmatic example of gene-culture coevolution.

As I explain in my Evopolitics 101 podcast, gene-culture coevolution is nothing new. Different societies’ military, economic, and religious traits have all impacted their populations’ reproductive success in different ways. Religion offers a powerful example in encouraging various forms of endogamy (intra-religious for Judaism, cousin marriage for Islam, intra-caste for Hinduism) which have well-documented impact in terms of ethno-genetic clustering, consanguinity, and susceptibility to different diseases. (Conversely, like Western Christianity and Buddhism, a religion may be indifferent or hostile to endogamy and value the spiritual life above reproduction, values which also have a genetic impact.)

As reprogenetic technologies become more widely adopted, this will hypercharge gene-culture coevolution. We already see this to some extent in more extreme national cases: Israel as a gene-conscious ethnostate trying to maximize births has embraced a form of techno-natalism which has led to over 5.8% of births being done via IVF and to population screening programs for genetic diseases by ethnic groups; by contrast Germany has adopted a more conservative approach where genetic screening is used only for the most serious genetic diseases and only following approval by an ethics committee. Israeli and German genetic counselors have sharply divergent on what reprogenetic interventions can be ethical, with the Germans being much more sensitive to criticism that an intervention is “eugenic” and therefore bad.

If reprogenetic technologies become easier to adopt and more powerful, over time adopting societies would benefit from greater population size, health, and enhancement. This would constitute a form of cultural-genetic group selection in their favor and other societies might increasingly feel tempted to adopt similar practices. I would expect the highest early adoption to be in nations combining a history genetic diseases due to endogamy with reprotechnological capabilities necessary to address them (i.e., Israel, the Gulf States, and perhaps parts of India).

It is interesting to put this Singapore study in the wider context of the history of hereditarian thinking in Southeast Asia. I wrote by master’s thesis at KU Leuven on the efforts of Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew to increase the birth rate of highly-educated women and lower those of less educated women in the 1980s. Lee was a big believer in the importance of free markets, heredity, and IQ. He was so alarmed at the imbalance in reproduction between educational classes (the least educated were having about twice as many children as the most educated) that he spent his entire 45-minute 1983 National Day speech discussing the need to tackle this.

Lee’s eugenic campaign lasted from 1983 to 1987 and featured policies such as public awareness raising and documentary series, a significant cash incentive (equivalent about one-third of a mortgage) for the uneducated with two children or less to self-sterilize, a graduate matchmaking program, and preferential school access for the children of graduate mothers with three or more children. The latter discriminatory program was by far the most controversial (and not, perhaps surprisingly, the self-sterilization incentive). The campaign was a big dud and led to unprecedented criticism for Singapore’s normally docile state-aligned media (publishing letters from women critical of the campaign) and to open criticism from MPs of Lee’s own party.

While some policies were kept on and adapted—namely differentiated financial incentives to have children and a broadened matchmaking program—overall the episode was a telling example of how overtly inegalitarian policies were rejected even in a culture such as Singapore, marked by a high degree of social competitiveness, low corruption, political competence, one-party rule, state media control, and relative conformism. The new study however suggests that while classical eugenic social engineering was found to be offensive, elective use of enhancement through reprogenetic technologies may be socially acceptable.

The strong support for PES among Singapore Malays is also noteworthy. Malays are a comparatively poor minority in Singapore and the country’s early independence was marked by race riots and tensions with majority-Malay neighbors Malaysia and Indonesia. In Malaysia, the Malay majority has instituted programs discriminating against the wealthier Chinese minority and has adopted an indigenist racial ideology affirming the special status of Malays as bumiputera (“sons of the soil”) as compared to the immigrant-origin Chinese and Indians.

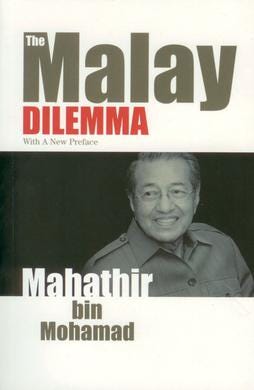

Like Lee, the longtime Prime Minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad was a deeply hereditarian thinker. In his book on race relations and the need for positive discrimination in favor of Malays, The Malay Dilemma, Mahathir asserted: “That hereditary factors play an important part in the development of a race is an accepted fact.” He wrote:

The effect of Chinese immigration on the Malays was conflict between two contrasting racial groups which resulted from two entirely different sets of hereditary and environmental influences. . . . For the Chinese people life was one continuous struggle for survival. In the process the weak in mind and body lost out to the strong and the resourceful. For generation after generation, through four thousand years or more, this weeding out of the unfit went on. . . . But, as if this was not enough to produce a hardy race, Chinese custom decreed that marriage should not be within the same clan. This resulted in more cross-breeding than inbreeding, in direct contrast to the Malay partiality towards in-breeding.1

Thus Mahathir suggested that some of Malays’ disadvantages were due to their cultural-genetic evolutionary history and presumably could partly be rectified by reducing consanguinous unions. One wonders if similar background thinking accounts for contemporary Malays’ remarkably high support for PES.

Quoted in Sunil Amrith, “Eugenics in Postcolonial Southeast Asia,” in Alison Bashford and Philippa Levine (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics (2010). Mahathir also wrote:

The Jews for example are not merely hook-nosed, but understand money instinctively. The Europeans are not only fair-skinned, but have an insatiable curiosity. The Malays are not merely brown, but are also easy-going and tolerant. And the Chinese are not just almond-eyed people, but are also inherently good businessmen. . . . It can be seen that these characteristics determine the relationship between races when they come in contact with each other.