No, populism isn’t building Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore

On certain “illiberal” temptations in the U.S.

There is a hunger for change on the Right, in America and elsewhere, beyond the strictures of what is called “liberal democracy.” What exactly is being longed for is not very clear. For one thing, both proponents and critics of “liberal democracy” rarely offer a clear definition of what seems to be an unstable concept. For another, the few right-wing intellectuals who explicitly articulate a vision beyond liberal democracy are not in agreement on what is the desired alternative.

For instance, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán of Hungary, Harvard Law Professtor Adrian Vermeule, and political theorist Patrick Deneen have each criticized the atomizing and demoralizing effects of liberalism and proposed variants of what might be called “illiberal democracy.” In contrast, tech billionaire and Trump backer Peter Thiel has written that he “no longer believe[s] that freedom and democracy are compatible” and, of the two, clearly prefers freedom. Far from advocating for illiberal democracy, then, Thiel seems to prefer a liberal (or libertarian) non-democracy.

The fact is that the current American Right has no consistent set of ideological principles or values. It is a loose coalition of highly heterogeneous elements—religious conservatives, free market conservatives, protectionist and welfarist populists, anti-immigration nativists, Zionists, the right-wing slice of Silicon Valley, and above all Trump’s personal following, among others. In the end, President Trump does what he wants, but that begs the question of what will come after him.

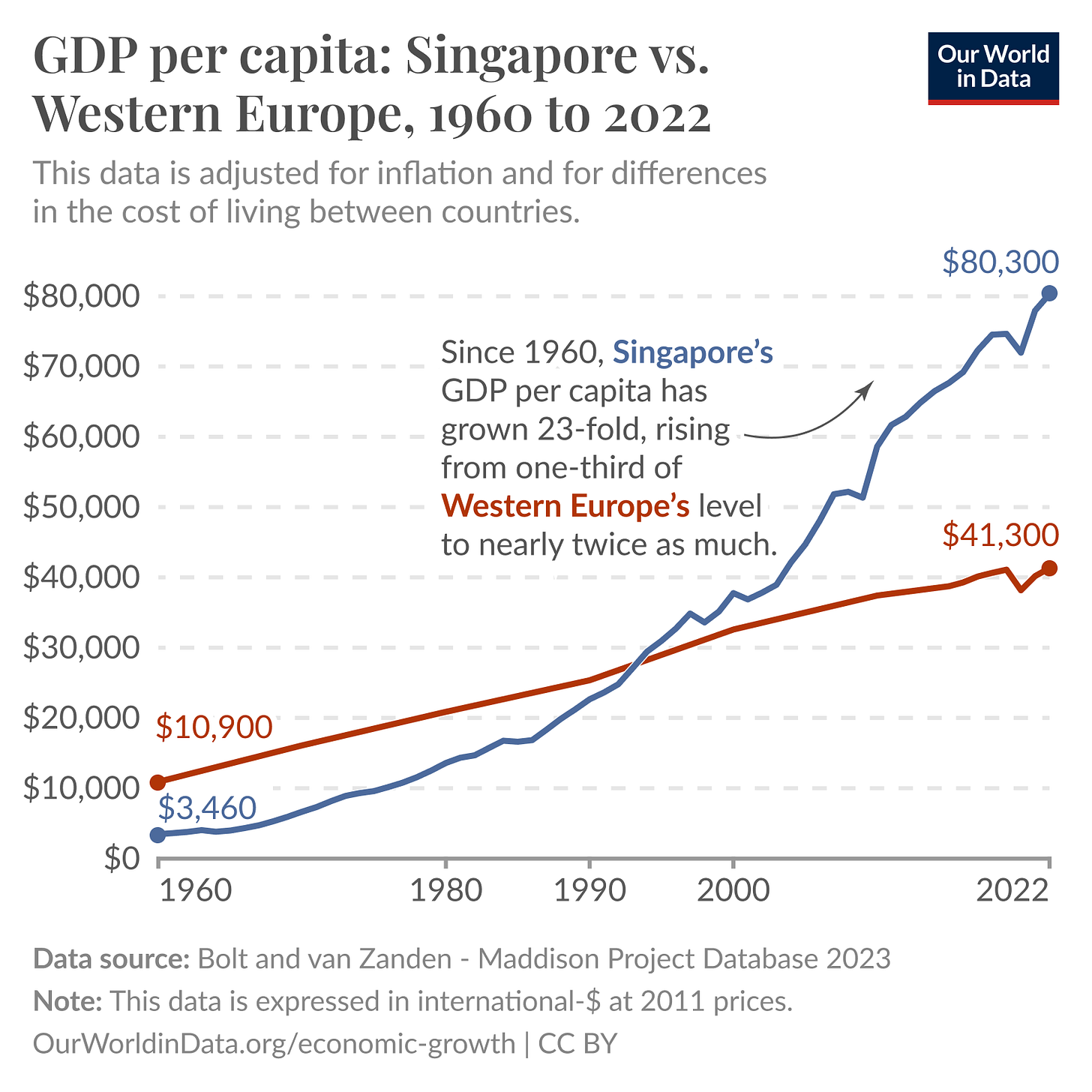

Rightists sometimes offer foreign models for their post-liberal vision. The example of Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore is often used to legitimize the idea of authoritarian governance, most notably by the influential Californian thinker Curtis Yarvin (also known as “Mencius Moldbug”). This example is probably the best that can be offered. Lee, who governed Singapore from 1959 to 1990 as prime minister and had advisory roles as “senior minister” and “minister mentor” until 2011, created a bone fide illiberal democracy which, by the usual metrics of development, well-being, and good governance, became the most successful in nation in Asia.

The country went from being a dirt-poor third-world country to becoming significantly richer than their former British masters. While Western economists like Daron Acemoglu and Joseph Stieglitz have written a great deal about why the third world is poor, and while development agencies have disbursed many Marshall Plans worth of aid in the effort to uplift the global south to Western standards of living, Lee Kuan Yew actually got it done. That makes him worth listening to. Lee’s memoirs, From Third World to First, are my top recommendation for anyone who wants to understand the realities of politics after 1945.

Singapore’s success was achieved in an unpropitious postcolonial context: a minuscule, insecure city-state’s unplanned independence from Malaysia; the hostility of its far larger and nationalistic Malaysian and Indonesian neighbors; racial tensions and riots among Singapore’s diverse Chinese, Malay, and Indian population; widespread militant communism among the Chinese majority; and the early withdrawal of British military protection in 1971. The Singapore miracle was anything but inevitable.

In a fairly dire postcolonial context, Lee and his colleagues organized the country around a clear, long-term vision. They instituted free trade and absolute respect for property rights and investment. Communists agitators and ethnic activists were jailed. English was imposed as a shared common tongue, alongside each racial group’s native languages. A meritocratic system of governance was established based on expertise and zero tolerance for corruption (widespread in the region). While the country was ostentatiously multiracial, Singapore’s immigration policy successfully aimed to maintain the country’s existing ethnic makeup (or “racial balance”), namely a 75% Chinese super-majority, which Lee (himself an ethnic Chinese) considered necessary to maintaining stability.

Speech by Lee Kuan Yew shortly after Singapore’s withdrawal from Malaysia (due to tensions with Malaysia’s Malay nationalist government). This is a durian.

With these measures, Lee managed to stabilize the country and trigger a virtuous circle of foreign investment (Western and Japanese), prosperity, and security. The rest is history. If the country now is as wealthy, secure, and innovative as it is, Lee’s leadership and unique system of government surely deserve a great deal of the credit, besides the hard work, discipline, and talents of the Singaporean people themselves.

Lee’s Singapore was not a liberal democracy. Such a system was felt to be too divisive and destabilizing for an insecure and multiracial young nation like Singapore. Lee also wanted to avoid what he saw as the decadence of postwar socialist British democracy, slouching into entitlement and stagnation. Under Lee, free speech was limited and the press was generally pliant. Elections were not rigged but were basically uncompetitive and not much more than “referenda” gauging support for the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) (which typically won 63% to 86% of votes).

Lee argued Singapore’s peculiar system meant the government could focus on expert long-term planning instead of making the kinds of demagogic short-term promises and rotating incompetent governments he saw in Western democracies. His criticism of Western democracy did not prevent him from being good friends with a wide variety of Western leaders, including Henry Kissinger, Margaret Thatcher, Helmut Schmidt, and many others.

Lee took pride in always being “correct, not politically correct.” Here’s a sample of the kinds of things he would say in his inimitable style:

There is certainly a lot to admire in Singapore’s successes. But for Western would-be authoritarians claiming Singapore as a justification, there are a number of problems.

For one, it’s not clear to what extent the Singapore model can be replicated in general. Lee Kuan Yew was one of a kind. I am aware of no other leader who combined a profound and dispassionate appreciation of both the remarkable strengths and weaknesses of liberalism, together with personal restraint and discipline. Authority in postcolonial Singapore was built on both the longstanding and deeply entrenched hierarchical nature of traditional and colonial Asian societies, and the particular crises newly-independent Singapore faced as a tiny city-state in the face of ethnic, communist, and geopolitical challenges. Remarkably, and practically uniquely among “authoritarian” leaders, Lee managed to sustain that authority in the long-term through a combination of victories at the ballot box, competent and clean government, and manifestly excellent results. (By contrast, right-wing dictators in South Korea, Portugal, Spain, and Chile may have enjoyed success for a time, but their system was always eventually discredited and torn down.)

Given his unique leadership and the particular circumstances of postcolonial Asia, Lee’s role as the founder of Singapore cannot be emulated in a straightforward way.

Secondly, it is not clear the Singapore model can be replicated in large states. There are many examples of successful small and economically open illiberal states. Singapore, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Rwanda are among the top performers in their respective regions. Small, open autocracies can arguably provide more stability, investment security, and potentially good governance than can the typical third-world democracy. As Amy Chua has explained, such democracies are often marked by nationalist and socialist demagogy, ethnic pandering and conflict, and corruption, when they don’t devolve into some variant of dictatorship or “mixed regime.”

However, large autocracies are far less accountable and far more likely to abuse power. Their capacity for autarky is far greater and thus they are far less responsive to the discipline of international capital and market flows. This being the case, there is no corrective mechanism should the regime cede to the temptation of abuse and corruption, as we see in Russia and China. The same would be true of a hypothetical authoritarian, and increasingly autarkic, USA.

Thirdly, one simply cannot compare Western populist movements with Lee Kuan Yew’s style of politics. Lee stood for expert government, limited welfare, anti-corruption, and respect for law1 (even when waging lawfare against his opponents) as fundamental pillars of Singapore’s governance. Who is supposed to represent anything like this agenda in the U.S. today?

Singapore could conceivably be a model of governance at the state level, which I think Yarvin has suggested. This would pose constitutional challenges—e.g., the provision in the Constitution that every state have “a Republican Form of Government.” However, unlike at the federal level, the risk of tyranny would be substantially mitigated by the fact that residents and capital could easily vote with their feet by moving to a different state.

Where illiberal democracy is concerned, some have suggested the U.S. could become like Orbán’s Hungary. This is more plausible, although again the U.S. is far larger, more complex, and by design more difficult to reform than a typical European nation-state.

What is striking with most illiberal thinkers, whether alienated Americans or anti-American Europeans, is their total lack of engagement with the U.S. political tradition. There is little attempt to understand American values—such as liberty, equal rights, and constitutionalism—and their enduring appeal. Nor, pointedly, is there much thought on the relationship between those values and American power, the world’s most decisive geopolitical fact for over a century. This lack of engagement seriously compromises illiberal thinkers’ relevance. Much of this is idle fantasizing rather than offering serious alternatives.

In America, any reform movement that ignores the nation’s moral(istic) core is unlikely to enjoy enduring success. Read Jefferson’s tortured prose on race and slavery, Washington’s speeches expounding a demanding republican ethos, or Lincoln’s compelling vision of a Union grounded in universal freedom, that is, the right of each individual to have a chance at shaping their own life. From the original break-away from Britain to Wilsonianism, enduring American political projects (whether one agrees with them or not) have been grounded in profound moral appeal.

This moral core cannot be dismissed, even if today much of it is channeled into wokism. Nietzsche despised Anglo liberalism and blamed modern European sentimentality on Christianity. I actually don’t think we even needed Christianity in that respect: northern European societies and their offshoots all seem to tend pretty strongly towards a moralistic “niceness” once prosperity and safety have eliminated the apparent need to be tough on others.2

Many illiberals take away from Nietzsche that morals are for rubes and from Carl Schmitt that legal norms are meaningless. All that matters, we are told, is imposing one’s will and crushing one’s enemies. Many think a brutish willingness to use force can make up for lack of moral appeal and institutional thought. Not for the first time in history…

By contrast, there are illiberal thinkers who did deeply engage with American thought and were the better for it. I think again of Lee Kuan Yew and of Henry Kissinger, two men who were deeply un-American in their moral assumptions.3 Yet, both were able to engage very constructively, indeed in very fecund ways, with the U.S. tradition.

I don’t believe the American system is one for the whole world. However, within its bounds, it is quite capacious, capable of producing and containing very different realities. Many alienated critics of Americanism seem to have never even heard of John Adams or Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. The American regime is a constantly evolving system whose ultimate trajectory cannot be prejudged. Even ambitious reformers should be careful in assuming that their goals cannot be substantially achieved, whether at the level of individual lives, communities, states, or even the nation, within the U.S. system.4

At the end of the day, as Paul Valéry didn’t quite say, dictatorship is a crapshoot. No one has thought up of good mechanisms to prevent even a virtuous despotism from degenerating into abuse and stagnation. On the other hand, democracies have their own foibles. Dictatorship, in the temporary Roman sense, may be necessary in times of crisis and refounding. But there is always great risk. You may get lucky with a Lee Kuan Yew, a de Gaulle, or an Atatürk, but most nations end up ruined by a Mao, a Mobutu, or something more mediocre still.

The despotic temptation makes especially little sense in America today. You may dream of dictatorship. Finally your views might prevail upon the whole country! But how do you know your ideological preferences will actually predominate in the new regime? And, if your shift to postliberalism is done through distinctly amoral mercurial populists, what makes you think they will serve your or any set of principles… rather than themselves?

To give an example, until 1989 in the highest court of appeals for Singapore was the Judicial Community of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, based in London.

After a trip to Scandinavia, Joseph Goebbels found the Swedes were far too cosmopolitan and pacifist to his liking, complaining in his diary: “Outwardly they are Germanic, but inwardly half-Jewish.”

The “self-evident” truths of the Declaration of Independence are probably not so self-evident to many people outside of Protestant northern Europe and its offshoots.

Personally, I tend increasingly towards a fairly radical federalism arguably in tune with the Constitution’s original meaning. That is, while ensuring equal political rights to citizens as guaranteed by the Civil War amendments, states ought in general to have great freedom to experiment in the creation of different kinds of societies. The most successful will naturally grow and attract people. The federalization of the Bill of Rights means the nine wise men and women of the Supreme Court are supposed to define and impose what, for instance, gun rights or non-establishment of religion philosophically mean, across an entire nation 340 million people, overriding their 50 state legislatures and supreme courts. Judicial restraint, no longer popular either among liberal or conservative justices, seems more advisable. Anyway, there is a very strong case to be made that the stakes of U.S. national elections need to be drastically reduced and federalism also offers one way to do that.

It is bizarre to me that so many on the American Right think that we need to invent something completely different to overcome our current problems. We do not need enlightened dictators like in Singapore or a monarchy or a right-wing federal government. Lee Kuan Yew‘s achievements are amazing, but they do not offer a model for the US. One brilliant leader can be succeeded by many incompetent and corrupt leaders.

No, we just need to get back to what once worked. The principles of federalism and checks/ balances embedded in the US Constitution worked great, but in more recent times we vastly centralized power in the federal government and particularly in the bureaucracy.

We don’t need perfect government. We just need to avoid the worst government across the 50 states, and let the rest of American society solve problems.

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/one-radical-reform-to-solve-all-our

"What is striking with most illiberal thinkers, whether alienated Americans or anti-American Europeans, is their total lack of engagement with the U.S. political tradition."

What Indeed I've always found amusing about modern American far right is they are as much as esterophile as the far left. While I can understand the far left fantasizing about making the US in best case a Nordic style Social Democracy and in worst case a Democratic Socialist Venezuela, right wingers looking for to apply foreign models to US reality is such weird and absurd, since they are implicitly declaring left wing cultural relativism is on point.

They are so immersed in their larping that they are completely unaware of the aims of what once was called "conservative revolution". It is not just about setting up a dictatorship (why not a Sunni Monarchy like Saudi Arabia, then?) , but to restore founding values of the nation. In the case of the United States, these values are found in Anglo-Saxon Protestantism: limited government, private property, personal responsability, and yes also a not so very welcoming attitude in face of foreigners. But to my surprise, when I tried to point this out some people answered me <<protestantism is gay and catholicism is "based">>. Do I have to remind them what their ancestors thought about Catholicism?