Europe’s Demographic Outlook: Insights from the Martens Centre

Fertility continues to fall, workforces are programmed to shrink, and labor migrants (mostly poorly qualified) make up only 17% of immigration to the EU

Europe’s worsening democraphic crisis, including the birth dearth, are starting to seriously attract the attention of policy wonks. The Martens Centre—the think-tank of the center-right Europe People’s Party (EPP), long the biggest and most influential political group in the European Parliament—has released many papers on demographic issues over the past year with a view to influencing the 2024-2029 term of the new EU Commission and Parliament. These studies highlight the gravity of Europe’s demographic outlook, outline some solutions, and are generally indicative of mainline center-right thinking which may actually impact policy.

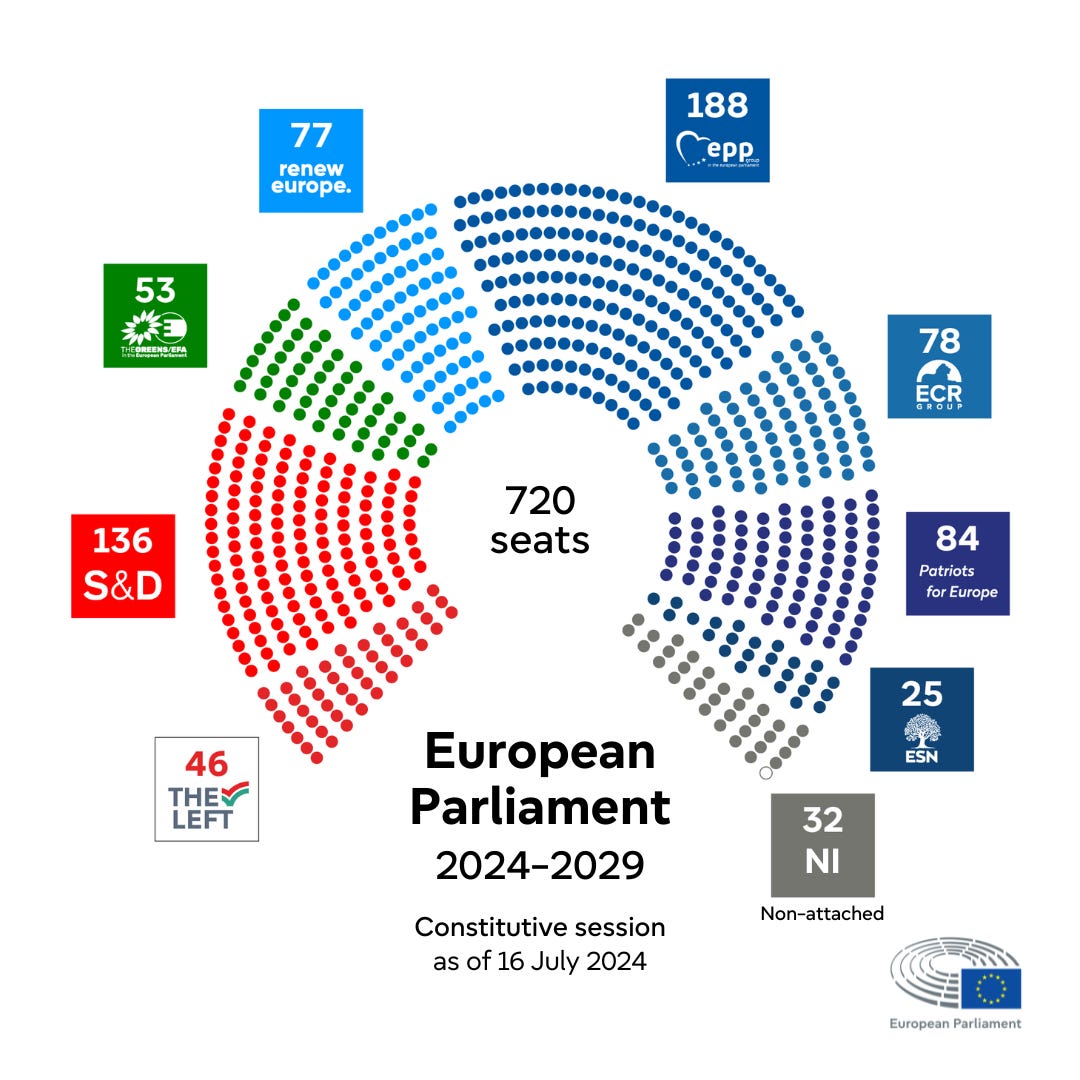

The Martens Centre’s analysis and proposals are synthesized in “Demography in Depth,” one of seven papers providing policy proposals for the new legislature elected last June. Incidentally, we saw a rise in the number of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) in conservative or nationalist groups for whom the demographic trends of birth decline and immigration tend to be core issues. (In contrast, the center-left, liberals, and especially Greens all suffered in the recent elections.) This may lead to a higher prioritization of demographic issues, even if the EPP has historically rejected working with nationalist parties at EU level1 (in the below chart, PfE and ESN are considered “toxic,” while ECR is considered handshakeworthy).

In their introduction to “Demography in Depth,” Klaus Welle and Vít Novotný warn:

Our institutions and policies are not ready for these [demographic] developments [of aging and fertility decline]. National social security systems lack sustainable funding. … In general, pronatalist policies in the form of cash transfers to young families have not fulfilled their objective. The EU’s population has been growing only thanks to immigration from outside the bloc, but family reunification—the most frequent type of EU-bound immigration—has not improved the ratios of workers to non-workers. In Southern Europe and Eastern Europe and in many regions elsewhere on the continent, depopulation and emigration are compounding the problems caused by aging.

These trends were worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, which coincided with a fall in births and disruption in the lives of young people. Current Eurostat population projections forecast a sharp decline in the working-age population and rise in dependent elderly:

Earlier this year, the Martens Centre had published an in-depth series of papers an issue of their European View journal focused on demographic issues which offer many insights.

Peter Hefele focused on the breakdown of any kind of common vision2 in European societies in the wake of political polarization, generational change, multiculturalism, and automation. He seems to suggest young Europeans are reticent to have children in this new, apparently aimless social world marked by uncertainty.

Gian Carlo Blangiardo, a leading Italian demographer and think-tanker, highlights the catastrophic consequences of the “demographic winter” in Italy. A few highlights:

The population of Italy (including foreign residents) shrank by 1.35 million people between the beginning of 2014 and the end of 2022. For similar decline historically, one has to go back to 1916-18 when the population fell by almost 1 million due to World War I and the Spanish Flu.

The share of elderly people (over 65) has almost doubled from 13.2% in 1982 to 23.8% in 2023, forecast to reach over 33% by 2043.

Annual births have more than halved from 980,000 in 1961-5 to 427,000 in 2016-22. The birth rate per 1000 has fallen over the same period from 19.1 to 7.2.

On immigration: “At the beginning of the new century, the contribution of the incoming foreign population, along with the related mechanism of family reunification, gave the illusion of a weak recovery, albeit one that was short-lived when faced with the economic crisis of 2008.”

The working-age population (15-64 year-olds) will fall by more than 6 million (!) over the next 20 years.

These demographic factors will lead (all else equal) to a 16.5% decline of GDP between 2022 and 2042, and a 25.7% decline by 2062. (Per capita GDP would decline by over 12% by 2042.) These are not unrealistic scenarios given that Italian productivity has significantly declined (!) since 2002.

Blangiardo concludes: “all national actors must cooperate to ensure the recovery of the birth rate, harness the economic benefits of incoming migrants, and the experiences of older people.”

Blangiardo urges removing barriers to parenthood and using “the tools of politics and culture” to encourage family formation: “All this should be done quickly, without any illusion of external help or magical solutions such as the important (but insufficient) contribution of foreigners, among whom the birth rate has halved over the last 20 years—from 20.35 per thousand in 2004 to 10.4 per thousand in 2022.” (That makes the foreign birth rate still about 50% higher than the native Italian.)

Blangiardo also advises moving to a mobile definition of the elderly from over-65s to people with 20% of expected total lifespan left.

Alexandra Tragaki, a demographer and advisor to Greece’s minister for social cohesion and family, provides a fine overview of demographic transitions in general, with a global shift from fears of an overpopulation “demographic bomb” to a “silver tsunami.”

She has a nice graph outlining humanity’s transition from the Malthusian death trap (high births, low life expectancy, fluctuatingly stable population) to modernity (transition to high life expectancy, low births, rising-then-declining population).

While the demographic transition is a global trend, Europe is the most “advanced” region, with over-65s already outnumbering under-15s and half of the population being over 45 (the average European voter is over 50, which no doubt explains the basic conservatism of party-political dynamics despite the constant talk of crisis).

Tragaki notes very cogently:

According to conventional wisdom, all other things being equal, a large population is supposed to be capable of defending its rights more efficiently, forwarding its claims more powerfully and laying down its conditions on the international stage more decisively than a small one. Paradoxically, an equally widespread conviction blames high population growth rates for poverty, resource scarcity, and political instability. Evidently, demographic considerations vary significantly across regions and time periods; however, the importance of population issues remains undeniable.

Tragaki also notes that demographic trends are unusually predictable:

Most of the people that will be alive in 2050 have already been born, and all those who will be over 65 are already here. Also already here are all the potential parents for the years to come, so their procreation is highly predictable.

Blangiardo, making the same point, calls this demography’s “inertia principle.” The booming aging population will lead to a “Silver Economy” driven by the elderly demand. Tragaki advises leveraging AI and robotics to respond to decline in workforce numbers and care for the elderly.

Ilenia Gheno, project manager of the AGE Platform (the pan-EU elderly advocacy group), highlights current EU policy reactions to population aging. This includes a so-called EU Commission Demography Toolbox presenting different measures taken in EU countries to support parents’ work-life balance, young and older people’s employment, and legal migration to address labor shortages.

Paul de Beer, a trade-union expert and advisor, argues that economic migration is only beneficial to the host country’s overall welfare if the migrants are more skilled in than the native average, especially if they settle permanently (eventually adding to the cost of schooling children and retirement). He concludes that “only selective and temporary labor migration will relieve the ‘burden’ of an aging society.”

There are also papers on increasing employment of people with low qualifications, understanding female migrants, helping rural regions (which acknowleges the transition to low-carbon food systems will be “costly” for farmers), and brain drain in the western Balkans and other countries joining the EU.

In a separate, 86-page study on immigration to the EU, Rainer Muenz and Jemal Yaryva found that of the 22 million people immigrants to the EU between 2013 and 2022, 49% were admitted for humanitarian reasons (i.e. asylum-seekers or refugees), 27% for marriage or family reunion, and only 17% for employment.

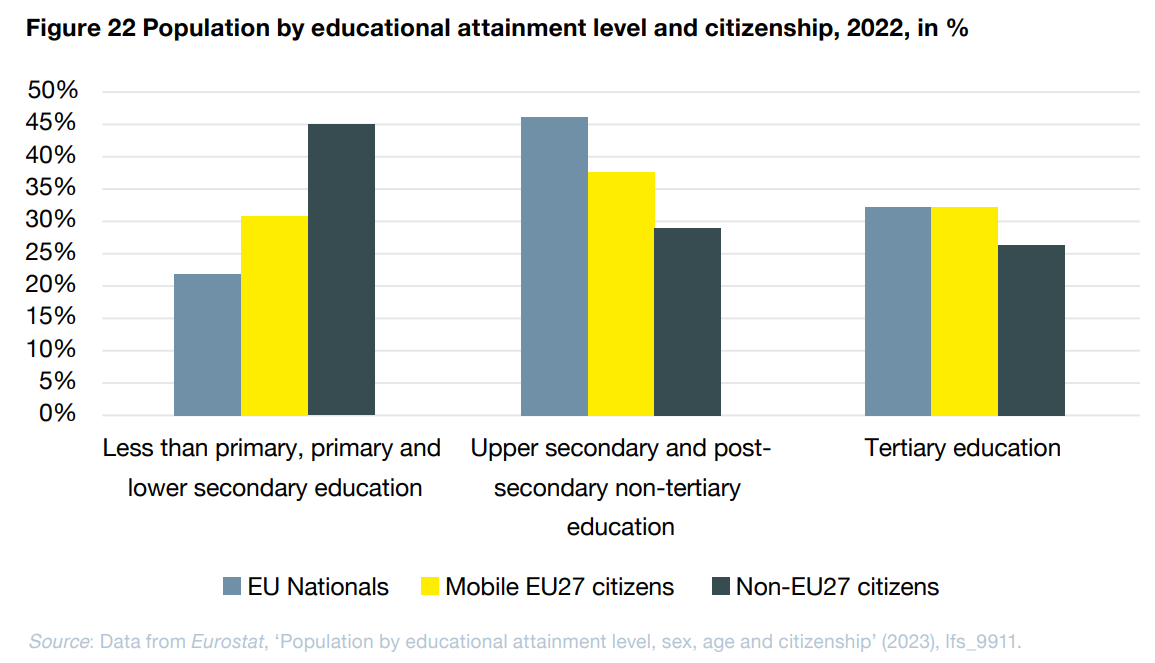

While intra-EU migrants (e.g., eastern or southern Europeans to north/west Europe) are about as educated and have slightly higher employment rates than the natives (about 74%), non-EU migrants are significantly less likely to be employed (59%). This is partly due to Islamic gender norms with women from Turkey, North Africa, and the Middle East having much lower employment rates (p. 20). In addition, almost half of non-EU immigrants do not have a high school diploma and their share of university graduates is lower than the EU average. Middle Eastern and North African immigration’s of low skills and low employment profile is highly congruent with Danish data suggesting these groups pay less in taxes, consume more in welfare, and are therefore a net fiscal drag and not an overall economic benefit to host countries.

In terms of solutions, the Martens Centre suggests a mix of policies to increase the birth rate and mitigate population aging. There should be child-friendly societies, more support for parents’ work-life balance, and more secure employment in general (often a driver for the decision to have children). Employment of young people, women (including migrant women), and older people should be increased. In light of 83% of migrants to the EU being taken in for non-labor reasons over the past decade, intake of migrants should should shift to using “employability as a key criterion for admission.” The Centre also suggests the establishment of an “EU-level office … tasked with exchanging best practices among the relevant national demographic policy bodies.”

One thing not mentioned in any of the papers is the main subject of my Repronews newsletter: the steady development and adoption of innovative reprotechnologies to enable reproductive choice, raise the birth rate, and reduce the burden of genetic diseases. Governments in Israel, California, Taiwan, and elsewhere have facilitated access to reprotechnologies like IVF for one or more of these reasons. French President Emmanuel Macron, with characteristic flamboyance, announced earlier this year a “great plan” to fight against infertility as part of France’s “demographic rearmament.” While different European countries are sure to have different approaches to reprotech, its potential to contribute to reversing the birth dearth should be recognized and leveraged.

The EU institutions’ legal competencies and resources to act on family-formation, immigration, and demographics more broadly are limited. Nonetheless, Mikuláš Dzurinda, former prime minister of Slovakia and current president of the Martens Centre, concludes demographic issues should be better prioritized by European policymakers: “We believe in completing the process of European integration by developing a genuine federation based on subsidiarity and sustainability, with demography being a key focus.”

The nation-states will remain in the driver’s seat on demographic issues. That said, governments still largely don’t know what to do to enable and encourage people to have more children. More research on what works best in different countries, exchange on successful practices, and simply a common recognition that the birth dearth represents an existential challenge would be worthwhile going forward.

The situation has varied at national level. Italy’s conservative parties have often co-governed with the “far right.” More recently, there has been a pattern of national governments taking office with the support of nationalist parties in Sweden, the Netherlands (including five nationalist ministers), and France. Nonetheless, conservative parties in many EU countries, including Germany, France, and Belgium, have so-called cordons sanitaires against working directly with nationalist parties.

Hefele notes that the center-right has traditionally been averse to grand social visions:

For good reasons and due to bad historical experiences, conservatives have always loathed the idea of “designing society” in the armchair, coffee house, or salon—the usual breeding grounds for fancy ideas in the long history of European social visions. Skepticism of the idea of (linear) progress and the human ability to govern complex societies, alongside the constant fear of creating an almighty “Leviathan,” have often prevented moderate conservative forces from entering the competition to conceive social visions.

Very informative piece. I know you are just conveying some suggested responses to declining fertility and not necessarily endorsing them, but I'd like to note that policies that sound like they should help may not and may make things worse. For instance, IVF is a wonderful thing but having taxpayers foot the bill may not only be expensive but quite possibly counterproductive. See the second half of this piece:

https://www.aier.org/article/trumps-subsidized-ivf-spells-disaster/