Predicting the Power of Nations

Demographics, economics, and why “based” regimes fail

The ebb and flow of different nations’ power is critical to the evolution of our world. Our lives might be very different if Napoleonic France had defeated Great Britain, if Imperial or Nazi Germany had won in either of the world wars, or if the Soviet Union had outcompeted America during the Cold War. Today, the United States, the European Union, Russia, and China all offer different visions for the future of the world. Which visions win out will depend, in significant part, on which nations have the greater amount of power to shape the world.

Underlying hard power capabilities tend to follow a relatively simple formula. Assuming a polity has a certain minimal State capacity—I mean the ability to raise taxes and mobilize for war—national power will tend to correspond to its aggregate economic and technological capacities.

In terms of great-power competition, economic and technological prowess will tend to determine overall outcomes (though not necessarily specific campaigns or local conflicts). In peace, people, especially brainy people, want to move to the more prosperous country and flee the poorer country. Economic and cultural elites in the poorer power often resent their poverty and urge regime change to the more prosperous system if possible. In war, the application of the latest economic, especially industrial, and technological capabilities to organized violence has been critical to military victories througout the modern era. In this sense, the story of modern geopolitics is the story of the triumph of technocapital.

Hierarchical and “hyperthymotic” regimes—for example, the Confederate States of America, Imperial Japan, Fascist Italy, or Nazi Germany—often emphasize manliness, martial virtues, and self-sacrifice as the key to military victory. While these are clearly important, in practice democracies, when feeling sufficiently threatened, have generally been quite good at military mobilization and the adoption of martial virtues. The decisive factor then becomes industrial production and technology. During War War II, Italy’s mediocre organization and economic-technological performance meant—all Fascist propaganda, posturing, and parading aside—that the country was if anything a military liability for Germany.

There’s a notable pattern where these honor-loving hierarchical regimes dare to pick fights with massive demographic-economic superiors. During the American Civil War, the South’s free white population was less than three times the size of the North’s. Northern industrial production was five times greater than the South’s. While it was not impossible that the North would be demoralized by early defeats and sue for peace, the odds were heavily stacked the power relying especially Southern chivalry. As Abraham Lincoln said on what generally determines the outcomes of wars: “I believe in the Providence of the most men, the largest purse, and the longest cannon.”

There was a similar situation when Japan chose to attack the U.S. at Pearl Harbor, instead of accepting Washington’s demand to withdraw from China. Japan’s population was about half the U.S.’s and its industrial capacity was an order of magnitude smaller. No wonder then that, given enough time, the U.S. could churn out far more naval ships and aircraft than Japan could. Ultimately, even the greatest samurai spirit—witness young Japanese men’s willingness to sacrifice themselves in kamikaze suicide attacks—was no match for the atom bomb. And I won’t even get into Adolf Hitler’s decision to go after the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and the USA all at once.

As a rule then, the greater economic and technological power tends to win. Not always of course. In a premodern times, virile barbarians often conquered emasculate peasants and urban-dwellers. Sparta defeated Athens, although that seems a bit of a fluke.1 More recently, Nazi Germany did beat the Anglo-French on the Continent in May-June 1940, albeit in a Blitzkrieg campaign, before the greater resources of the Allies could be fully mobilized. The general pattern is unmistakable: the power combining the most scale, wealth, and technological prowess tends to win out.

What then are the sources of economic and technological power, which underpin broader national power? I would argue:

national power ≈ economic-technological power ≈ population size * human capital * marketness

Population size, or more precisely working-age population size, is self-explanatory. Human capital refers to a population’s cognitive, social, and other skills that make humans effective in a modern industrial or knowledge economy.

By “marketness” I mean basic market institutions that enable private investment, creative destruction of industries, and (re)allocation of resources, notably to invest in and deploy technology. Marketness is undermined among other things by instability, market fragmentation, and corruption, and requires at least enough social trust to ensure honest exchange and secure property.2

So, assuming basic military-fiscal State capacity to mobilize resources for warfare and foreign policy, national power will tend to converge according to these demographic and market-institutional criteria. We can then make predictions about future national power trends, with varying degrees of certainty, in the following areas.

1. Demographic trends: High certainty

Demographic trends are among the “stickiest” and most predictable. Today’s babies are tomorrow’s workers, while today’s workers are tomorrow’s pensioners. The brutal dents left in a nation’s population pyramid by events like World War II in Germany or the famine of the Great Leap Forward in China remain visible decades later.

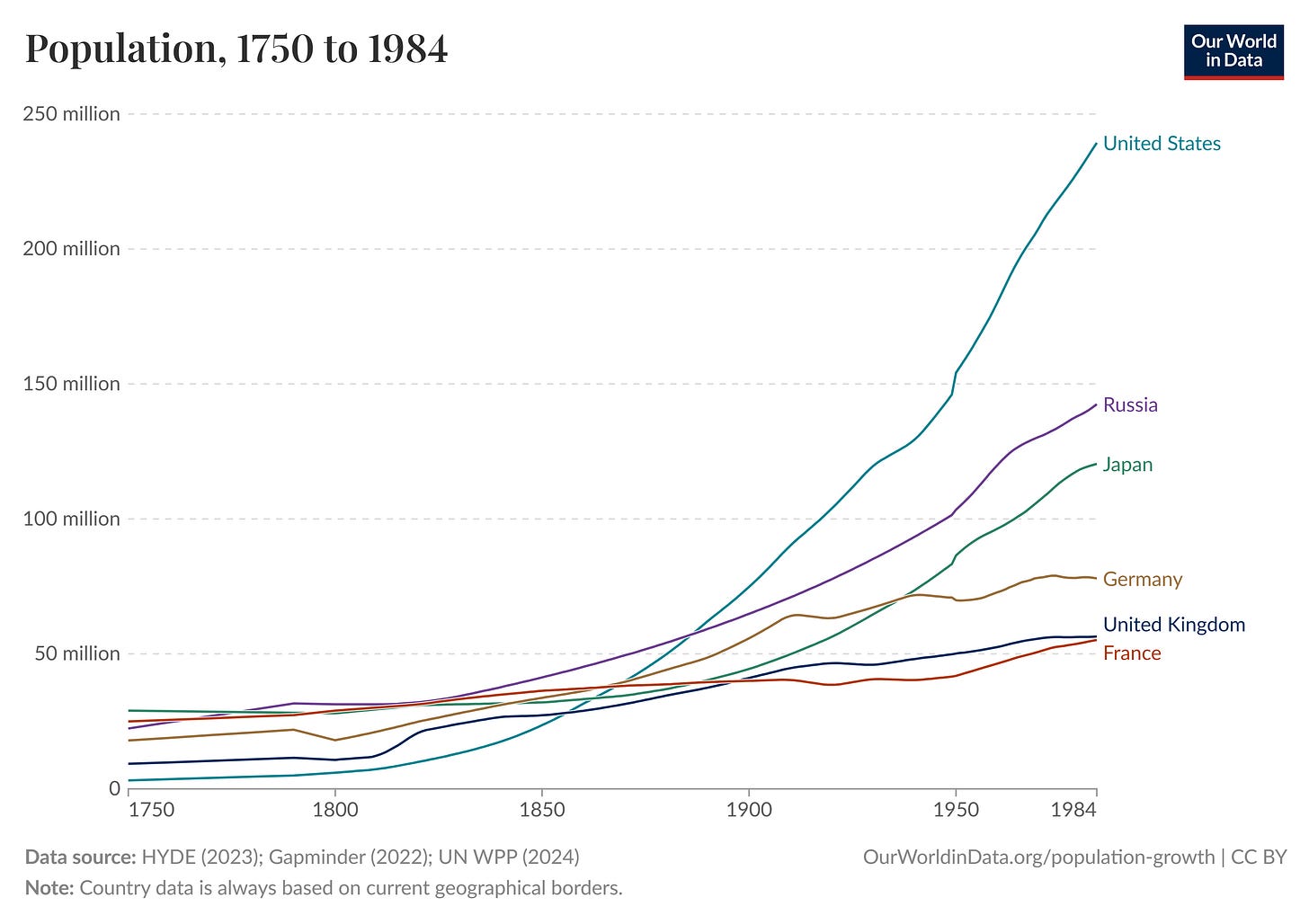

All else being equal, population equals power. On this simple basis, Benjamin Franklin in 1751 (!) could predict English-speaking North America would surpass the British imperial motherland within a century. Alexis de Tocqueville could say in Democracy in America—in 1835, just over a century before the Cold War—that the United States and Russia each seemed “marked out by the will of Heaven to sway the destinies of half the globe.”

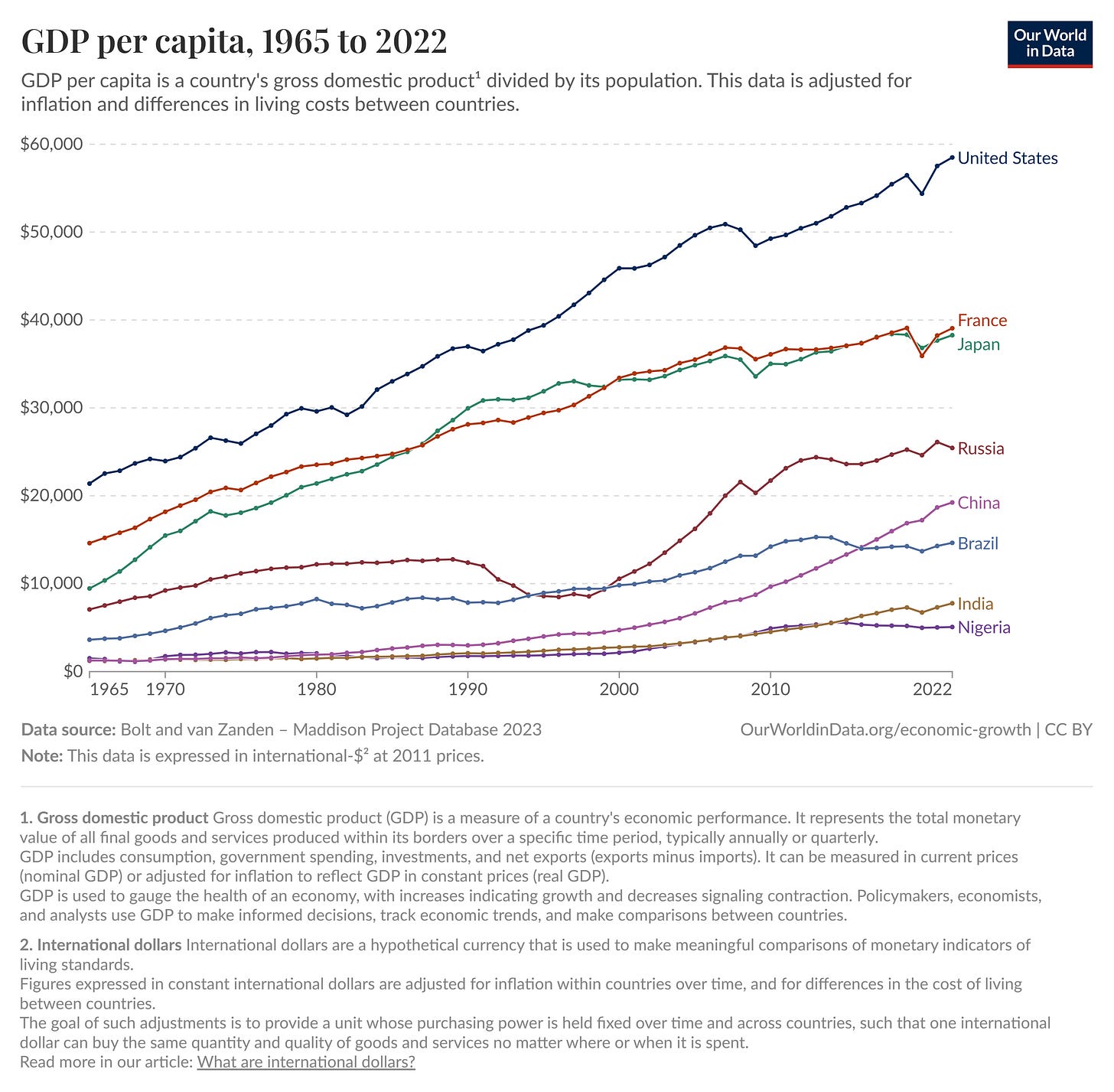

Of course, there is more to national power than simply a large population. India and Brazil have large populations but are not superpowers. However, for a given nation, you can usually project that your current power (absolute and relative) will evolve proportionally to your demographic growth or decline. If your number of workers grows (as in the U.S. over the past decades), you will likely be that much more powerful. As your number of workers declines (and especially as your share of elderly dependents grows), your underlying power will proportionally decline (as in Japan and Italy today).

In most cases, it is reasonable to project your previous long-term average socioeconomic performance into the future. Really, nations’ relative socioeconomic performance is remarkably stable. For the most part, it’s when a nation’s economic performance is artificially depressed—as in cases of prolonged civil war or communism—and that these conditions are removed, that we see lasting changes in the rankings (as in the case of China and much of post-communist Europe).

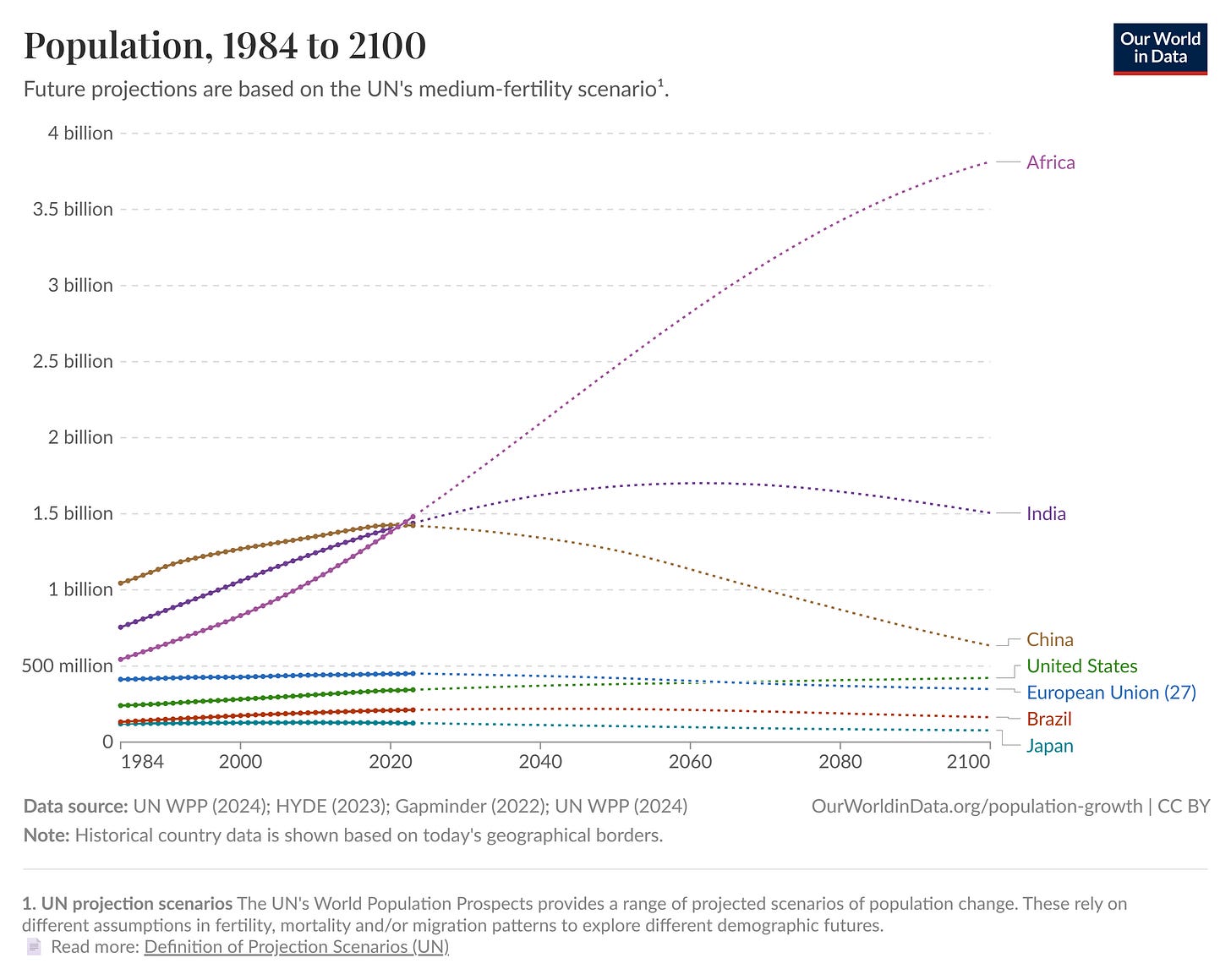

Very long-term demographic projections should be taken with a grain of salt, especially as forecasters do not know exactly how fertility trends will evolve. So far, fertility rates in most countries have fallen much more than UN demographers expected and the trend shows no sign of abating. Still, overall, you should at least integrate the default demographic forecast as your baseline scenario for who will make up future humanity and what will be changing demographic weight of nations.

All in all, the sheer predictability of sub-replacement fertility’s consequences—in terms of national finances, power, vitaly, and innovation—is the main reason I advocate techno-natalism to mitigate the problem.

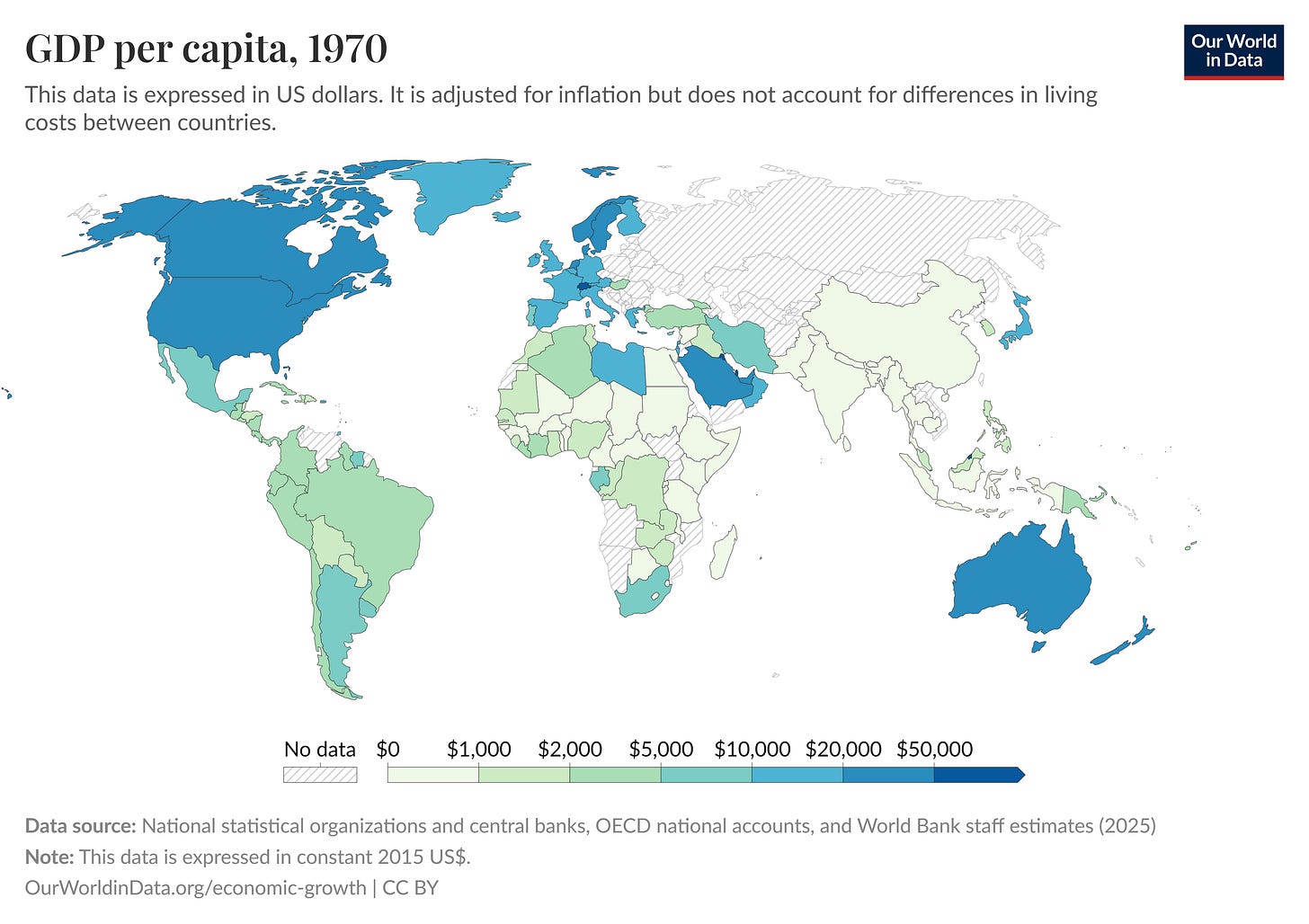

2. Long-term economic trends: Moderate certainty

Short term, one cannot predict the boom-and-bust cycles of the economy. Medium term, the performance of nations also tends to fluctuate according to decade-long cycles of industrial decay and renewal (yesterday’s cutting-edge industries become uncompetitive, time is required to shift to new sectors). Long term however, economic performance seems to track a nation’s human capital and marketness pretty closely.

Again, and some fluctuation aside, the rankings since the 1960s haven’t change all that much, except when caused by marketness: East Asia rose when rejecting communism, post-communist Central-Eastern Europe rose when integrated within the European Union (partly because of EU aid, but I think mainly because of the security implied for domestic and international investors3), and the United Kingdom escaped uncharacteristic economic underperformance after the reforms of Margaret Thatcher undid much of the postwar socialist consensus. If you are lucky enough to be ruled a Lee Kuan Yew, you may even overperform your human-capital fundamentals, but that is a rare thing.

On the basis of current human capital and historical performance, Latin America, Africa, and India are unlikely to fully converge economically with the West, and thus remain relatively marginal powers.

“Marketness” is the most uncertain variable here. It can change due to policy choices, political upheaval, or sociocultural changes. These changes are hard to predict. Will Russia overcome its debilitating corruption with 50 years? To what extent does the Chinese political system distort the economy and mask dysfunctional behavior in damaging ways? Hard to say, for me at least.

3. Technological transformation: Certain, yet unpredictable

World history, human life, and geopolitics have been repeatedly transformed by technological breakthroughs and their deployment. Think of the printing press, gunpowder, the steam engine, electrification, automobiles and armored tanks, aviation, the atom bomb, or the computer and the Internet.

Each of these technological breakthroughs had sociopolitical consequences. The printing press enabled the Protestant Reformation, leading to the bloodiest wars of religion in European history, and to broader transformations of European culture with rising literacy. Social media has led to an explosion of innumerable subcultures of highly uneven value, including the enabling of left- and right-wing populisms. Tanks, aviation, and atomic weapons transformed warfare and geopolitics. Etc.

There is no doubt future innovations will continue to transform our world. However, much is uncertain: Which innovations will actually work? When will the breakthroughs occur? And what will be the nature and scale of their impact?

Friends of mine are sometimes very confident in their technological predictions: this epic transformation will happen, and very soon! All I can say: maybe; and: we’ll see!

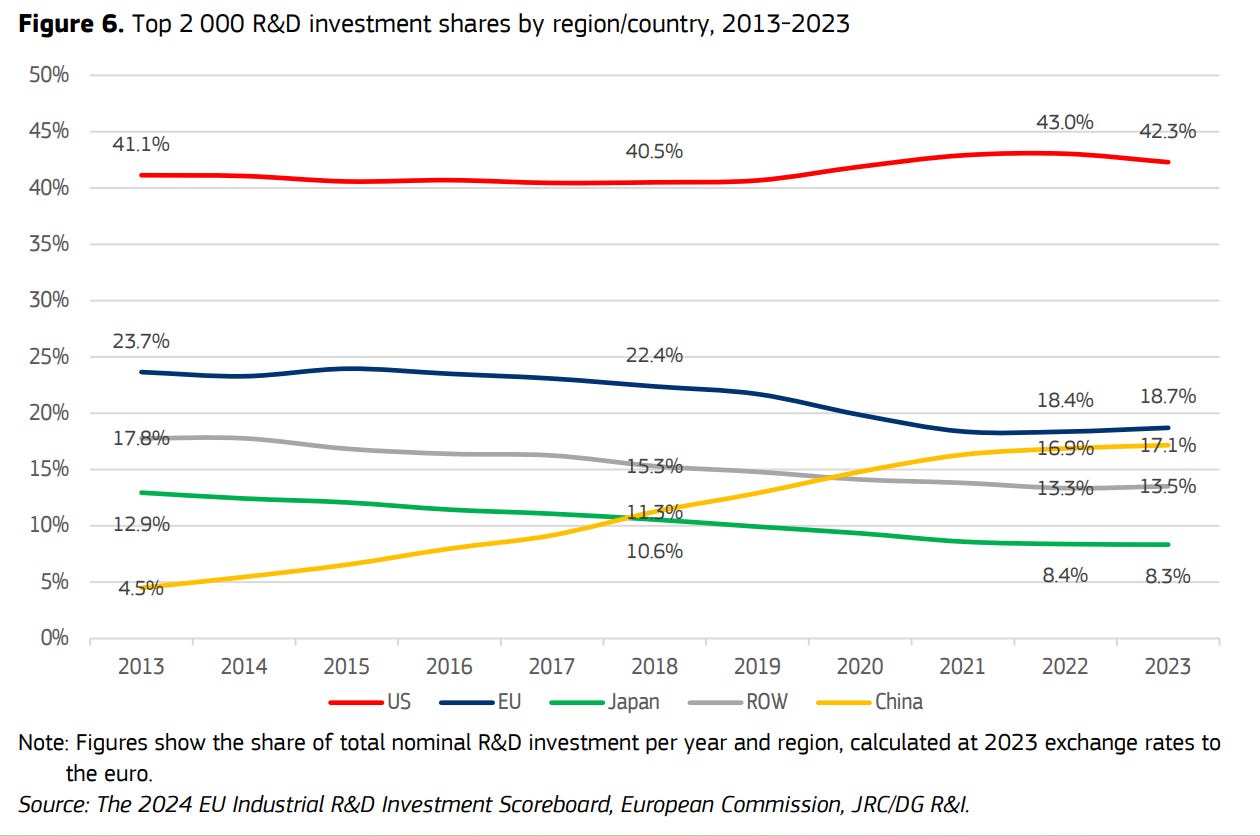

Certainly, AI, biotechnology, fusion power, and/or many other technological breakthroughs will transform our lives this century. But it is hard to be much more specific than that. We can be reasonably certain the innovations will take place in the most economically/technologically competitive powers—today this is the United States and China—which will further entrench their dominance, at least until other powers can replicate their innovations. Over time, people will claim the benefits of many of the innovations made by the pioneers are a human right and these should be spread equitably across the planet.

4. Local geopolitical / military conflicts: Unpredictable, often overrated

Great powers often compete in proxy wars or in bids for influence in other countries. The outcomes of particular military campaigns and games of influence are often difficult to predict.

I think the impact of such events on overall power-political trends is often overstated. The U.S. defeats in Vietnam or the War on Terror didn’t matter nearly as much for long-term American power as did America’s demographic, economic, and institutional fundamentals. As Paul Valéry said: “Events are the foam of things; the sea is what interests me.”

5. Regime change and world wars: The least predictable

The advent of major political upheavals and military conflicts is arguably the least predictable, and one of the most critical, variables. No one in 1900 could have confidently predicted World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, the Great Depression, and the rise of Nazi Germany. And even if you predicted one of these events, the timing and implications would be beyond forecasting.

One might have predicted, as some people did, the fall of the French Ancien Régime or the collapse of the Soviet Union, based on their economic difficulties and their elites’ growing lack of belief and confidence in their official ideology. However, the timing and nature of such developments—necessarily depending on individual leaders, mass unrest, and often messy contingent circumstances—are essentially unpredictable.

So, on the scale of 50 or 75 years, we cannot predict:

Will the U.S. and China engage in a major war? (Still by far the most plausible great-power war scenario.)

Will the EU break apart, federate, or continue to muddle through?

Will U.S. economic, technological, and geopolitical capacities significantly deteriorate because of a lasting shift towards Argentine-style populism, incompetence, and corruption?

Will the U.S. break apart through hyper-polarization?

Will the Chinese Communist Party lose power?

Will the Putin regime be replaced by a liberal, Western-oriented regime at some point?

I might have my own guesses on these questions, but they remain mere guesses. So, in forecasting, I say: look to demographics and to nations’ long-term economic performance for your baseline scenario. Political thinkers and policymakers can and should plan on that realistic basis. For the rest—namely precise technological breakthroughs and military-political upheaval—I think things are necessarily uncertain. Hedging may be smart.

PS: I did not include soft power, including cultural power, as this does not seem amenable to long-term prediction.

Cultural power seems to depend partly on one’s general power factor (basically economy and scale, enabling a large domestic cultural market, and potentially making your country attractive/prestigious), a minimum of cultural liberalism, and rather idiosyncratic factors, like whether one’s domestic culture can be broadly appealing to (certain) other countries. Beyond that, cultural appeal seem very hit and miss: K-pop, Japan’s anime, Bollywood, telenovelas, and Turkish soap operas are popular internationally. On the other hand, China, Russia, and most of the rest of Europe’s international cultural influence is relatively weak compared to their economic and/or geopolitical weight.

The U.S. seems to be the world’s cultural superpower due to scale, a highly competitive and scale domestic cultural market, English as global lingua franca, and cultural industries oriented towards multicultural / global audiences. For similar reasons, and in no small part by leveraging the legacy of the British Empire, Britain is able to massively punch above its weight culturally. The impact of Anglo-American cultural hegemony in shaping other countries’ perceptions of what is “normal” or “prestigious” should not be underestimated: shows like The Simpsons, Friends, and Sex and the City shaped non-Americans’ (especially young people’s) view of reality; films like Saving Private Ryan and Schindler’s List have recentered narratives on World War II on the U.S. perspective and the Holocaust, and Anglo-American academia largely sets the tone of scholarly research agendas, frameworks, and pecking orders.

Soft power generally seems to broadly track the general power factor—especially economic weight—but is heavily modulated by regime type and foreign policy strategies. The U.S. and the EU pioneered a model of soft power characterized by the appeal of liberal norms, a predictable international order, trade, and aid, institutionalized through elaborate international organizations. The Trump administration is largely abandoning this soft-power tradition. China for its part has a narrower form of soft power defined by a relatively restrained foreign policy (compare China’s wu wei-like approach to foreign affairs with America or Russia’s foreign policy hyperactivism) and aid deals lacking the normative strings of Western donors. Today, Russia’s soft power is tending towards zero, but for much of the Cold War the Soviet Union had significant appeal to socialists and anticolonialists across the world, providing many allies in the form of spies, opposition parties, revolutionary movements, and postcolonial states. How will soft power dynamics evolve into the distant future? I sure don’t know.

PPS: A reader highlights that I completely ignored natural resources and land in this post. Natural resources are indeed an important component of national power, as these may enable both wealth and, perhaps more importantly, autarky. This has certainly been an important factor of European dependence since the collapse of the colonial empires. Land is historically an important component of national power but arguably less so over time as the share of agriculture in the economy has fallen. As time goes on, national power tends to more and more reflect human capital and institutions, rather than land.

I think, given Sparta’s extraordinarily leveraged and insecure demographic situation, Athens lost because of its strategic mistakes rather than inevitability.

I don’t want to get into what degree of “marketness” is needed to be economically effective. At a mininum, market economies in general are much more effective than communist economies. The rise of China following Deng Xiaoping’s capitalist reforms could be predicted on that basis. There is a case to be made that, in general, more market-based economies like the U.S. and Switzerland also beat out non-communist but more statist and redistributionist ones. I must say, based on my experience, that I have grown very skeptical of the ability of government to make worthy investments, outside of areas of basic infrastructure and natural monopolies where these may be inevitable: The incentives and knowledge are just not there. I do not deny that that a competent regulatory State acting according to realistic objectives can effectively supervise a market economy (see postwar France and, perhaps, China today). However, the tendency for overreach in the form of overregulation and excessive redistribution—killing private investment and innovation—must be recognized. I follow the Draghi Report in its assessment of the causes of the EU’s economic decline relative to China and, especially, the U.S.

Compare the institutional and economic trajectories of, say, EU members Poland, Hungary, and Romania with comparable countries which have remained outside the EU, like Ukraine, Serbia, and Moldova.

The power of a nation-state by no means consists only in its armed forces, but also in its economic and technological resources; in the dexterity, foresight and resolution with which its foreign policy is conducted; in the efficiency of its social and political organization. It consists most of all in the nation itself: the people; their skills, energy, ambition, discipline, initiative; their beliefs, myths and illusions. And it consists, further, in the way all these factors are related to one another. Moreover, national power has to be considered not only in itself, in its absolute extent, but relative to the state’s foreign or imperial obligations; it has to be considered relative to the power of other states. Correlli Barnett

Fantastic essay. I love how you like to deal with big issues that span huge time periods. I try to do the same in my Substack.

I would add one more point, as the industrialization process moves unevenly between nations, it upsets the pre-existing balance of power, which can lead to unpredictable results. This is particularly true for nations that already have a large but poor population base.

I am specifically thinking of UK, Germany, USA, Japan, Russia, and China.